‘Authenticity’ in branding – How real can you fake it?

It was three years ago that I first coined the term ‘the little guy’ as a growing trend in brand positioning. I referred to the increasing number of small, specialist brands apparently driven by passion, expertise and quality, all values that were perceived to be lacking in many cost-optimised, advertising-fuelled brands of the past.

These ‘little guy’ brands moved quickly from their natural habitat of the delicatessen onto supermarket shelves, where their weapon of choice was packaging. Carefully designed to tell their story of honest, rugged, low-budget authenticity with great conviction, it was a new story that most mainstream brands couldn’t begin to copy, because when they tried it instantly smacked of quickly created, inauthentic copies of the ‘real’ thing.

So when Kellogg’s jumped on the Dorset Cereals’ bandwagon with ‘Nature’s Pleasure’, we could all sense the hollowness of its brown box and chatty copy, written in seven different hand-drawn-effect typefaces. It didn’t last, because it missed the point of what people were buying – a story they told themselves about ‘Dorsetness’, and about aspiring to be quite posh country people with understated style and taste: best served with a new Barbour jacket and Hunter wellies in your Smallbone kitchen.

As it dawned on corporations what was really happening, they adopted plan B – we’ll have to buy them – and they all lived happily ever after, it seems. Certainly brands such as Ben & Jerry’s, Green & Black’s and Innocent seem to have thrived under the ownership of three of the world’s biggest food and drink companies. And just as our marketing textbooks predicted, the ‘trend’ of the authentic has filtered down to the new and bigger wave of the ‘early majority’, leaving the trailblazing early adopters to go find something even more real.

As more and more product categories get the authentic treatment, this has led to a fascinating arms race: away from that giveaway ‘perfect’ look, in search of the most hand-made, least designed or shabbiest chic. Imperfection is the new code for honest, as long as you haven’t been telling us about ‘perfect’ for 50 years and suddenly switch sides.

Most of the proud new owners of acquired authentic brands seem to understand the asset they have bought, and that there’s no going back to business as usual. They can’t drop the passion and maybe some of the more expensive ingredients, to be replaced with ‘communication’. In the internet age of growing transparency and dialogue, consumers have stopped being passive recipients of ‘campaigns’, and they are looking for something meaningful in everything they buy: No meaning, no brand loyalty, and no sale (unless it’s on promotion this week).

Making a virtue of no-frills honesty gave Ronseal a unique brand personality, and made its strapline ‘does what it says on the tin’ the exact opposite of ‘because I’m worth it’, but equally valuable as a branding device.

But for me the high point (so far) of a new wave of truth-telling authentic brands comes in the form of Scottish brewery Brew Dog and their brilliantly named beers, from Trashy Blond to Tactical Nuclear Penguin. The flagship and my new favourite brand, Punk IPA, comes with a manifesto in place of sales copy that includes an interesting take on a brand promise: ‘We don’t care if you don’t like it’.

Behind the aggressive language is a very compelling message of passion for the brewer’s craft, together with a salvo of heartfelt abuse aimed at ‘mass-marketed, watered-down beers’.

Of course global multinationals were once start-ups once too, with all the passion and expertise for their product of any Johnny-come-lately little guy, and this seems to be a better fightback strategy than making-up stories of small-scale production that don’t hold water.

Danone in Europe has started to tell a (true) story about the sourcing of their milk from local farmers, a long-standing reality but one which was easily forgotten on a shelf loaded with more overtly authentic packaging.

Personally I’m not convinced by the visual treatment of a glass pot inside a plastic cup, on the real plastic cup (!), but I am surprisingly OK with a similar trick being performed by Danish juice brand Rynkeby.

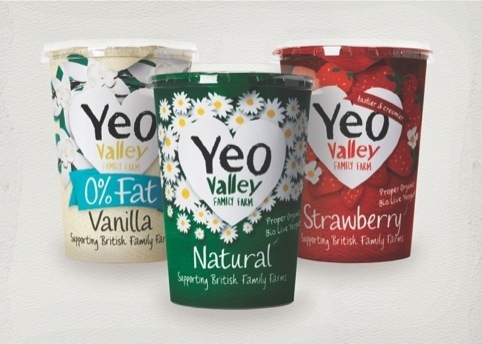

‘Yeo Valley family farm’ as we must now call them have always had a true story to tell, yet in October 2010 they opted for a new design which focused on pushing brand impact and neglecting the ‘soul’ of the product. This clearly flopped, so now another relaunch sees Yeo Valley wearing its heart (quite literally) on its sleeve.

What all of these examples share is a blatant denial of the realities of modern mass production in large, clean, efficient but ultimately soulless factories, because we, as consumers, want to hear (and see) a different story even though we know it isn’t true.

As Albert Einstein famously observed: ‘The pursuit of truth and beauty is a sphere of activity in which we are permitted to remain children all our lives.’

I think he means it’s far more fun, and perfectly authentic, to live with a bit of make believe.

Steve Osborne is a partner at Osborne Pike.

I couldn’t agree more about Brew Dog. A completely new take on brewing. Thank God.

Steve, I do think that ‘passion’ should be a new entry in ‘Bullshit Bingo’. It’s overused and most often a lie. I just came across a company called Portable Toilet Hire in Bristol. Their strap line? “We only do toilet hire and we’re passionate about it”. Je reste ma valise.