City scope

On the eve of the UK’s first major retrospective of avant-garde architectural free-thinkers Archigram, Pamela Buxton assesses the group’s lasting influence on the architects and designers of today

‘When we churned out the stuff way back we had no idea the drawings might endure, that folks might want to look at them years later,’ says Michael Webb, one of the six original founders of Archigram.

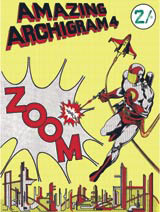

As the surviving members gear up for their first major London retrospective at the Design Museum, it’s clear that Webb has been well and truly proven wrong, even if it has taken nearly 45 years for a definitive show to happen. But then Archigram, established in 1961, never did follow a conventional path. Experimental, visionary, playful, optimistic, the group is widely acknowledged as comprising some of the most influential and original thinkers in post-war architecture, broadening the boundaries of what was perceived to be architecture and devising amazing forms for new ways of living with projects such as Plug-in, Instant and the iconic Walking City. These were communicated in a distinctive and accessible graphic style, which helped bring architectural theory into the realm of pop culture.

Although it had no built legacy of its own, Archigram’s influence, particularly through teaching, has been huge, believes Alice Rawsthorn, director of the Design Museum.

‘The ideas and images propagated by Archigram are key references to contemporary architects and the spirit of the group – its playfulness, zest for experimentation and love of fantasy – has an enduring appeal,’ she says.

But it’s not just architects. Established set designer (and architect) Mark Fisher freely acknowledges Archigram’s enduring influence on his work, which currently includes a new venue for Cirque de Soleil in Las Vegas.

‘I had [founder member] Peter Cook as a unit master in the Architectural Association. I was influenced back then and still am,’ Fisher says. He is interested in their use of technology and emphasis on the mobile and the flexible. This has clear relations to his own work in creating robust, movable structures to house an experience created by special effects.

‘The Archigram idea of tramping in and doing a show and moving out is very much part of what I do,’ he says. ‘A lot of what I think of as our most interesting work has had a moving, mechanical component of some sort. My interest in architecture that moves is something I’ve been playing with since the 1960s.’

Younger generations have also been inspired by Archigram. When Alex Mowat of design group and architect Urban Salon, which recently completed a store concept for Marks & Spencer, was at art college in the late 1980s, Archigram wasn’t on the curriculum. He discovered it anyway, delving into work such as the Hedgerow Project – a hotel for 16 000 people – and Living Log, an underground living pod.

‘People felt architecture had to be serious and [Archigram] was flippant. There was a sense of fun and of engaging with other technologies. What I found fascinating was [exploring] where architecture stops,’ says Mowat.

When he set up Urban Salon, Mowat says he was able to explore some of Archigram’s ideas in his own work, and was particularly struck by ‘the sense of understanding projects at a glance from the diagrammatical drawings – all the guts are hanging out – to show how they work and how people use them’.

At the M&S store in Liverpool, for example, Mowat says he aimed to make the physical space instantly explanatory and ‘as pure as a drawing’ in terms of legibility and circulation. He finds Archigram’s ideas still pertinent today. ‘It was about doing a lot with a little – building lightweight structures and doing as much as you can with as little material as possible – building very efficiently.’

Catherine Croft, director of the Twentieth Century Society, considers Archigram to be the major contributor to post-war architectural debate along with the Smithsons, who also influenced different areas of art and design with their ideas: ‘They radically questioned the way you live – family groupings, women working, people being more geographically mobile, the basic premise of whether you need a building.’

Archigram’s ideas remain ‘immensely relevant today’, adds Dennis Sharp, co-chair of Docomomo, a group promoting modern architecture. ‘I wonder if the Gherkin [Norman Foster’s Swiss Re building in the City of London] would have come about without the loosening of the canon of architecture that Archigram brought about, especially the flexibility and ambiguity of city landscape,’ he says.

Archigram’s Dennis Crompton is loathe to talk about how the group has influenced others’ work ‘because it tends to reduce’ the person concerned. Nonetheless, he adds: ‘We’ve all been teaching for 30-odd years and if you multiply that by 20-30 students a year you do have quite a degree of influence.’

The biggest contribution of the Archigram founders, according to Richard Rogers Partnership partner Mike Davies, who studied under them at the AA, was that they created a student environment that was ‘liberating, enthusiastic, and trusting’. And while they themselves were primarily theorists, they ‘laid a carpet from which the seeds of building architects took root.’

As for his own work at RRP, Davies sees a similar loose-fit, liberal, non-hierarchical approach and a general suspicion of monumentality and formality, ‘although it would be dangerous to only attribute that to Archigram’.

At the Design Museum show, working with in-house curator James Peto, the Archigram crew has cooked up something a little bit special. At the entrance there’ll be a recreation of Archigram’s office with stacks of magazines for making collages and all sorts of ephemera. Further in, Archigram plans a mini-recreation of its Log Plug concept plus a multi-screen, multimedia Archigram Opera presentation showing its work, influences and place in architectural theory. Images such as the famous Walking City will be blown up huge to bring the space to life.

As well as spectacular installations, such as two gigantic Instant City Airships, the show will include elements that have never been exhibited before. Hopefully, says Crompton, the lively presentation will engage not just the Archigram devotee but those with no previous exposure to the group, thus ensuring that Archigram continues, after all this time, to spread the word.

Archigram, 3 April to 4 July at the Design Museum, Shad Thames, London SE1. Contact 020 403 6933 or www.designmuseum.org

Potted History

Established in 1961, Archigram was a collective of architectural thinkers named after an abbreviation of Architecture and Telegram. Its founders – Peter Cook, Dennis Crompton, David Greene, Michael Webb, Ron Herron and Warren Chalk – became famous for experimental ideas such as Walking City and Hedgerow City, disseminated in the magazine Archigram, which accumulated a considerable overseas following. Of the original six, four survive and are still working. Webb is now based on the East Coast of America. Cook is head of school at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. Crompton is the prime mover in staging various exhibitions and managing the archive. Greene is developing a landscape and robotics project at the University of Westminster’s Centre for Experimental Practice.

Neither Herron nor Chalk lived to see Archigram awarded the prestigious Royal Institute of British Architects Gold Medal in 2002, a belated official acknowledgement of its tremendous influence.

-

Post a comment