Alternative smoke signals

With tobacco advertising now stubbed out and giant on-pack health warnings becoming the norm, cigarette branding is changing. Hannah Booth reports

New York’s restaurants and bars inhaled their final lung-full of smoke last week as the city’s smoking ban came into force. As with other Big Apple trends like hip hop and brunch, it may not be long before similar legislation hits the city’s British sister, London.

It is another nail in the coffin for the tobacco industry, already reeling from the advertising ban that came into force in the UK in February and looking nervously ahead to October when it becomes mandatory to use giant, sobering on-pack health warnings such as ‘smoking kills’.

It’s debatable whether New Yorkers will be persuaded to kick the habit, and the design implications in restaurants, such as removing segregated areas and no-smoking signage, are minimal. But for smokers the dining experience will change irrevocably and restaurants may lose business.

Conran Restaurants’ New York eaterie, Guastavino’s, has made no physical changes to adapt, a spokeswoman says. An existing exterior terrace is now used by smokers.

Conran & Partners director Paul Zara thinks the ban is likely to be introduced in London.

‘With so many things led by the US with us following, a ban will probably come to London,’ he says. ‘But in a world where more and more of our lives are restricted by petty bureaucracy, let’s see if we can hold off this particular restriction for a little longer.’

Zara says the design of smoking-related products, such as ashtrays and matchbooks, will suffer under New York’s ban. Conran Restaurants’ iconic ‘much stolen’ ashtrays, designed by Conran & Partners, are an example, he says.

He suggests there are ways round minimising smoke indoors. ‘You can help mitigate the effects of smoking with ventilation, separate smoking areas and air extraction systems,’ he maintains.

Conran Restaurants may be bullish. But with restaurants in one of the most influential cities in the world expelling smokers and cigarette advertising now banned in many countries, tobacco companies are being forced to consider different ways to attract consumers and build brand awareness.

Packaging is becoming an increasingly important weapon in their arsenal. British American Tobacco is looking hard at the packaging of its many cigarette brands, including Lucky Strike, Kent and Dunhill. Two factors are impacting packaging design, says global packaging innovations manager Richard Stevenson.

‘Our traditional methods of communication are being eroded so we’re having to find alternative ways of marketing our brands,’ he explains. ‘And there’s increasing demand for space on packs from both health regulators and brand owners, and the two are coming into conflict.’

The future lies in creating alternative pack designs, says Stevenson. ‘Different materials and pack sizes will be used increasingly to differentiate between brands.’

Brand descriptors such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ that, according to regulators, make unfounded health claims, will also be outlawed in October. But the law on descriptors is a ‘nonsense’, according to Imperial Tobacco marketing manager Peter Manzi.

‘If there’s confusion among consumers as to which sub-brands are high or low tar, because the packaging is not explicit, they’ll opt for the packs they know – the stronger, original ones. And that’s endangering their health,’ he argues.

Imperial Tobacco has chosen to differentiate its sub-brands such as Lambert & Butler Gold and Superkings Blue, formerly ‘light’, by colour rather than description, in case there are further changes to the law on wording, Manzi says.

Design Central has revamped the company’s brands across the UK and Europe (L&B pack pictured). It has been a mammoth task, particularly as legislation and timings vary in each country, says account manager Kate Gibbons.

‘UK health warnings are the biggest in Europe and consume 30 per cent of the front and 40 per cent of the back of packs respectively, excluding the 3mm thick black border,’ Gibbons adds.

The refresh involved more than just squashing the existing design up the pack. The lack of space meant the group had to identify the most important element of each brand from research and use that as a starting point, says Gibbons. With Embassy & Regal, it was the crest, which it retained, but reduced it in size.

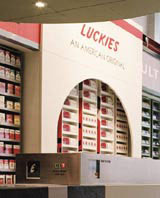

In the absence of billboards, tobacco companies are also turning to retail environments as a communications vehicle. BAT’s Lucky Strike brand opened a contemporary tobacconist in Amsterdam in 2001 called 451°F (the temperature at which paper burns), designed by Fitch London, to play on Lucky Strike’s iconic status. It has an urban convenience store and a smokers’ lounge complete with nightlife information and a ticket service.

But companies are nervy about being perceived as trying to outsmart health legislation and, particularly, attract young smokers with sexy brand extensions. BAT has scaled down the 451°F venture to in-store branded areas and is currently rolling them out across northern Europe.

‘Tobacco companies’ marketing focuses on encouraging existing adult smokers to switch brands rather than persuading young people to take up smoking,’ says Fitch London associate director of design Alasdair Lennox.

If that were true, tobacco companies would have a non-existent market in as little as 60 years, and they’re unlikely to let that happen. They may be losing the battle against clean air campaigners and health regulators, but they’re not kicking the marketing habit just yet.

-

Post a comment