Knowing rite from left

Hugh Pearman believes the design landscape adapts to the national political mood, and being able to interpret the undulations makes good business sense

Peter York, the man with the sharp suits and improbably perfect hair, once described the character of Britain – by which I think he meant England – as ‘punk and pageantry’. He said this on television in front of a live audience, among which was Janet Street-Porter and her then boyfriend, a member of a band called Sigue Sigue Sputnik.

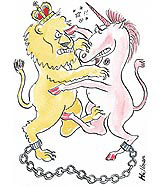

York was right, though scarcely original. He was revisiting a venerable tradition, in which we English look at ourselves and decide that, as a nation, we have a split personality. Michael Frayn (today a playright and novelist, but in those days a newspaper columnist) described this split in 1963 as a matter of herbivores versus carnivores. He was remembering the 1951 Festival of Britain (a triumph of the herbivore tendency), which itself took a look at the national character and decided it was a matter of the lion and the unicorn. The former was bluff, no-nonsense, practical and bellicose. The latter was dreamy, creative, artistic and idealistic. It went back to the old nursery rhyme about the lion and the unicorn fighting for the crown. The national character was, in this view, enshrined in the royal coat of arms.

Politically speaking, lion and unicorn are right and left, Cavalier and Roundhead, Tory and Whig. Winston Churchill and Clement Atlee, if you like. In this version, the right likes pomp and circumstance, military bands, coronations, state funerals and jubilees, the Last Night of the Proms, anything else traditional such as the Chancellor’s tatty old Budget box. The left likes the Festival of Britain, Cool Britannia, Powerhouse:UK, the Dome, the Commonwealth Games and anything purposeful and forward-looking such as the Chancellor’s shiny new Budget executive briefcase. For a while after 1997 things got a bit confused as right and left came together in the centre, the Tories tried for a while to seem nice and caring, while Labour tried to court big business, and hold down public spending (except on wars). But both sides are reverting to type now. They can’t help it, it’s in the genes. We English aren’t bothered either way. We let one side take control for a while, then when they get too cocky or incompetent, we kick them out and get the others in for a bit. That’s the voter’s ritual. Every once in a while, we get in touch with the other side of our character.

It is all part of the strange business of being part of a Janus-faced nation. Such thoughts raced through my mind recently as I attended one of the most ancient and ritualistic of all things English. A friend had finished her lawyer’s training and was being called to the Bar. Or, in the language of the Middle Temple, called to the Utter Bar.

How old is Middle Temple Hall? Let’s just say that Shakespeare premiered Twelfth Night there. And the ritual enacted there has changed as little as the architecture, since it was James I who set up today’s legal system. I swear some of those yellowing horsehair wigs, hired by the graduating students for the event, date back to that time. It’s all flummery and nonsense, of course, as ridiculous as Black Rod hammering on the door of the House of Lords once a year. A modernised legal system, like a modernised Parliament, would do away with all that. Yet there’s something lurking in all that needless ceremonial that attracts recruits from just about every ethnic grouping. Must be the fees.

Presumably the trappings of barristry are just one of those things, like policemen’s helmets and red telephone kiosks, that it is best for us not to get too self-conscious about. Best to forget that such oddities are in our midst. Then neither the carnivores nor the herbivores can claim them. Because if they do, it becomes another, and destructive, kind of ritual, summed up by the endless argument about what is the best corporate livery for the planes of British Airways. Can you think of anything worse?

It’s over-simplistic to make out that the championing of good design is always a herbivore activity. I can think of several eminent carnivores who show more than a passing interest in the matter. Hard though it is to remember now, there were Tory design champions as well. But the design landscape does change subtly with the national political mood. What it comes down to is this: learn from the Saatchis. Their genius was to catch the swing from grass-nibbling to flesh-tearing at exactly the right moment, just as the architects of New Labour deftly caught the swing back the other way. This tidal movement will go on forever. As with any business, it is only ever a matter of getting your timing right.

-

Post a comment