Imagine Moscow at the Design Museum: a frightening depiction of Soviet Russia

The museum’s new exhibition looks at the unrealised, communist architecture of Soviet Russia alongside propaganda posters from the era, and it entices visitors to draw parallels with society today.

The Design Museum’s latest exhibition Imagine Moscow explores 1920s and 1930s Soviet Russia through its architecture and design, offering a unique look at the political motivations of the time.

Through architectural sketches, graphics and posters, the show not only reveals a political agenda of the past with design used as a powerful propaganda tool, but also frighteningly draws parallels with the world today.

The exhibition was curated by Eszter Steierhoffer, with exhibition design by Berlin-based architectural practice Kuehn Malvezzi and graphic design by UK-based studio Kellenberger-White. It is divided into seven sections, with six based on proposed architectural projects that were never realised. The last section is the only one based around an existing building – Lenin’s Mausoleum, where communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin is buried in Moscow’s Red Square.

Although a snapshot of a real era in history, the exhibition reminds visitors of a fictional, dystopian novel. Steierhoffer refers to the six unrealised buildings that frame the show as “phantoms”, all of which were based around a proposed social purpose, such as democratising education, encouraging health and wellbeing and freeing women from their traditional role in families.

These buildings include Leonidov’s Lenin Institute, a huge library of 15 million books which aimed to make “all human knowledge” accessible to everyone; Sokolov’s Health Factory, a relaxation retreat on the coast of the Black Sea; Ladovsky’s Communal House, a commune which looked to diminish the idea of the housewife; Lissitzky’s Cloud Iron, a horizontal skyscraper concept which aimed to reduce overcrowding in Moscow; Iofan’s Palace of the Soviets, a monument set to be the tallest building in the world; and the Commissariat of Heavy Industry, a huge government building.

The exhibition space features monochrome, angular wall displays throughout, which encourage visitors to walk in spirals around the seven sections and its exhibits. While these shapes reference constructivist art – a movement in Soviet Russia which centred around practicality and social purpose – they also aim to create a “surprising” experience for the visitor that is not restricted to a historical timeline, says Wilfried Kuehn, co-founder at Kuehn Malvezzi.

“The spiral shape requires active movement and generates surprising views between different exhibits,” he says. “The exhibition’s curation revolves around the ‘phantoms’ without any hierarchy or chronology, which work both as a series and as autonomous parts.”

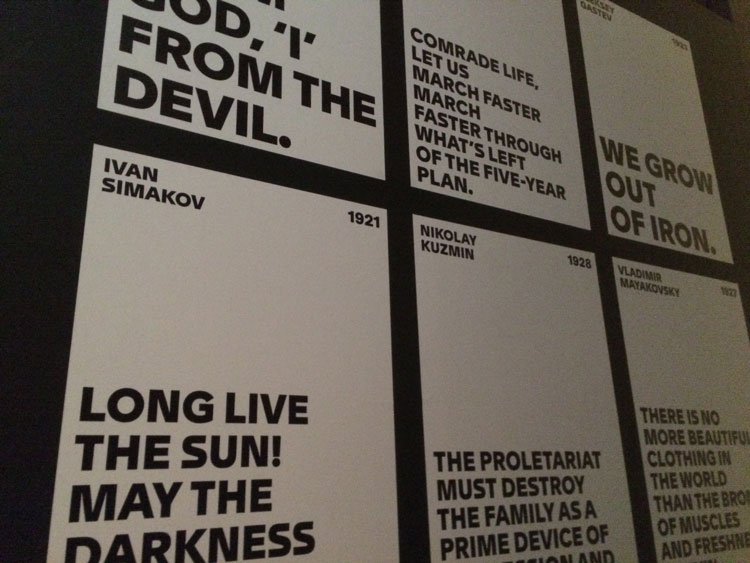

Sitting alongside the “phantoms” is a selection of real life propaganda material from the era, including posters, magazines and newspapers, alongside drawings, graphics, textiles and other artwork.

Although these posters were actually publicised and disseminated in Soviet Russia, the language used adds to the sense of the imaginary too. Propaganda material displaying phrases such as “Peasants and workers! You mastered the rifle, now master the quill!” remind visitors of something they might have read in George Orwell’s 1984 or Animal Farm.

Steierhoffer refers to this similarity. “Like the architecture, the propaganda also appears unreal and imaginary,” she says. “The ideas promoted by propaganda posters are quite far from reality. The unrealised architecture and the propaganda are not dissimilar.”

These gargantuan buildings and optimistic posters present the conflict between dystopia and utopia that runs throughout the show. These proposed constructions looked to empower people with the democratic sharing of knowledge, the liberation of women from traditional family roles, and skyscraper solutions for overcrowding. But at the same time, they restricted and trapped people within an enforced “happiness” and order.

The exhibition space reflects this quite aptly, situated within the claustrophobic basement of the Design Museum, confusing and entrapping its visitors behind various angular pillars. At the same time, this confusion liberates the visitor as they are discouraged from approaching the show chronologically and instead discover the different themes of the show in their own way.

There are scary comparisons that can be made between this imagined Soviet world, and the real world we live in today. A giant sculpture of Lenin’s finger is a key exhibit, three times the height of a human. This is the remnant of a huge statue created of the Soviet leader, which was meant to sit on top of the Palace of the Soviets, which was set to be the tallest building in the world.

Current US president Donald Trump proposed a dividing wall between Mexico and the US border in the run-up to the election – a momentous, unfathomable project which many believed to be unachievable. But the US Government just recently put out a call for architects to pitch their designs for the project last month. It is yet unknown whether this terrifying project will stay unrealised or go on to be a reality.

Equally, Sokolov’s Health Factory was intended as a relaxation retreat on the coast of the Black Sea, which would include individual pods for resting, alongside a communal hall for eating and exercise. This idea of an isolated wellness centre has cult-like connotations which are not dissimilar from the “workplace happiness” environments cultivated by big tech companies like Apple and Google, which make it so that employees never need leave.

Imagine Moscow is both a fascinating look at a forgotten era and a scary interpretation of the present day and future, intensified by the high-rise-style plinths and displays that fill the space, and the regimented, orderly monochrome graphics infused with block colours such as socialist-associated red.

“We wanted an exhibition design that makes you feel close to the aesthetics of the 1920s, and shows you how familiar it is to us today,” says Kuehn. “The Stalinist aesthetics of the 1930s is also very close to the hyper-capitalist high-rises that we see today.”

And the overarching message of the show is not just to show the remarkable design and architecture of the time but to emphasise the part it played in society and politics.

“Gender politics, globalisation, communal ways of living, the cult of leaders – it’s all so relevant today,” says Steierhoffer. “The political ideas behind these works are completely undervalued and under-appreciated. I hope this exhibition opens the topic up – there is so much more history to be discovered.”

Imagine Moscow has been put on to mark 100 years since the Russian Revolution. It runs from 15 March – 4 June 2017 at the Design Museum, 224-238 Kensington High Street, Kensington, London W8 6AG. Tickets cost £10 for adults, and £7.50 for concessions. For more information, head to the Design Museum’s site.

-

Post a comment