Profile: Inga Sempé

Furniture and lamp designer Inga Sempé’s fascination with technical details gives her work an idiosyncratic touch. Despite international success, she still has a passion for Paris, says Natasha Edwards

Tiny maquettes clutter the shelves of Inga Sempé’s studio: tables made out of wire and brown parcel paper, larger versions in cardboard, miniature armchairs in crudely stitched foam. The French designer has become known for her lamps and furniture, but it was a fascination with objects that brought her to design.

‘Objects have always interested me,’ she says, a discovery she made as a child on weekly visits to the Paris flea market with her illustrator mother, or objects in the drawings of her father, the cartoonist Sempé. Although she now goes less often, she still loves the flea market, but is also fascinated by eBay. ‘It’s another universe. It’s a very random way of discovering things,’ she says.

‘I always wanted to make technical objects, rather than furniture or lamps. In the beginning, I didn’t consider all those objects that can be assimilated with decoration. I wanted to design tools, telephones, locks, door handles,’ she says. Some objects develop from sketches, then are rendered in 3D; more often she starts from flimsy models. Apart from brief stints working with Marc Newson and Andrée Putmann, Sempé works on her own, which, she explains, makes it easier to propose furniture or lamps to a manufacturer than items for mass production, such as a pressure cooker.

Unlike many of her fellow graduates of the École Nationale Supérieure de Création Industrielle in Paris, who are happy to tackle anything from logos to luxury hotels, Sempé has no desire to move into interior design. ‘I am not interested in creating a total universe. If they want to put one of my lamps next to a sofa that is ugly,’ she says, ‘that’s fine by me.’

Like many French designers, however, Sempé bemoans the lack of innovative French furniture companies. ‘In France, very few companies are interested in young designers. It is not like Italy,’ Sempé says. It was Italian manufacturers Cappellini and Edra that gave Sempé her first break.

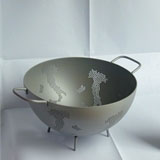

Sempé refuses to define her style, other than a ‘horror of the 1970s’ and a desire to make things that ‘are different, but not different and stupid’. She particularly admires the work of Konstantin Grcic and Vico Magistretti. ‘Both of them make things that are simple, yet very different. There are plenty of people who do things that are simple, that are banal and boring. With Grcic, it’s simple, yet very elaborate,’ she says. Rather than an aesthetic, with Sempé you notice a taste for technical details and little idiosyncratic touches, reflecting her initially quiet, yet very quirky personality: Brosse storage units for Edra (2002) were made out of industrial brushes, a lamp for Cappellini (2002) turns and rotates. ‘It’s true I like articulated objects. It’s a big fault,’ she says, with self-deprecation, rare in France.’It’s more expensive, it’s fragile. If I could change myself I would.’ A case in point is the raising table, Lunatique, she designed for Ligne Roset, which has a ring pull so you can raise or lower it with one hand (while holding that TV dinner tray in the other), and which then folds flat into the table top, locking it in position.

Perhaps the item that best defines Sempé’s approach is her clock. Still a prototype, though it has been patented, you can tell the time both by the hands and on a digital display, readable at all times. Before it can be put into production, a new motor has to be developed, as the hands are heavier than on a conventional clock. But it’s a system, she insists, that could equally be applied to weighing scales or car speedometers.

Despite the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris, an exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 2003, and an international presence at conferences in Sweden, Mexico and this year’s Design Indaba in South Africa, it’s only recently that she’s been able to truly live by her design. As well as a lamp and sofa, still to come for Ligne Roset, she has recently completed a table for Swedish company David Design, and has projects in the pipeline for Cappellini, Edra, Magis and Luceplan, as well as a one-off chandelier for Baccarat, which will be put up for auction.

Asked what her dream commission would be, she becomes almost fierce. ‘I’d like to be in charge of all the street furniture in Paris. It’s a disaster,’ she says. ‘I want to be in charge of the bus colours as well – I’d remove that horrible Chernobyl green. I would be detested, but I am ready for that. I would need a bodyguard, but I am ready to be a tyrant for anything that concerns Paris.’

-

Post a comment