Dyson victory is landmark case for design rights

A long-running court case, which concluded last week, served to clarify the reach of design rights in common law.

The outcome of the case strengthens the rights of designers to claim ownership of visual work, after spare parts company Qualtex was judged to be infringing Dyson’s design rights on visual grounds.

Bringing to a conclusion the three-year battle between the two companies, three judges in the Court of Appeal ruled that Qualtex’s sale of copies of Dyson components is unlawful, upholding an earlier ruling in Dyson’s favour by the High Court (DW 13 January 2005).

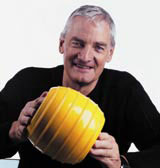

‘There is precious little to prevent other people from copying you and the design right is a relatively new law that hadn’t been tested,’ James Dyson told Design Week. ‘This case shows how important design rights are, especially for small design companies and individual designers, who don’t necessarily have the means to protect themselves legally against people who copy their designs.’

Although UK legislation does permit the copying of features which allow a spare part to be attached to the original product, Lord Justice Jacob decided that the visual design of these parts may not be reproduced, because it can provide added value to a product. The judge argued that consumers are likely to have more confidence in a part that looks the same as the original, broken one, whereas a different-looking part might create ‘sales resistance’.

Dyson claims that the Qualtex parts, although built to fit Dyson machines, are sub-standard when compared to the company’s own, so the visual association damages its reputation.

However, Andy Robinson, solicitor for Qualtex, notes that the court ruling requires that only two of the 14 parts under dispute be changed, one of which has already been redesigned.

For designers, the judges’ decision clearly establishes that the common law design right includes the visual elements of a design. ‘This makes design rights much clearer and is good news for everybody, even potential infringers, because they know where they stand,’ asserts Dyson.

Design rights are gained automatically by a designer whenever an original design is created, without the need for registration. This right runs for ten years, whereas a registered design right carries a 25-year term, according to Richard Davis, a barrister specialising in intellectual property at Hogarth Chambers in London. ‘As design rights are fairly short term, the threshold of what constitutes an original design tends to be lowered by judges and can include additions to existing product lines,’ he says.

Dyson and Qualtex are now in negotiation over the value of the settlement for costs, damages and licence, the proceeds from which will be donated by Dyson to the Royal College of Art, to promote the ‘welfare’ of the college’s product design students. Although a final sum of money is yet to be agreed, Dyson says the winnings will be ‘substantial’.

‘There’s been much talk about intellectual property. Design rights are an under-publicised and very important example. Many individual designers and small agencies cannot afford to defend their design rights and tend to be exploited as a consequence,’ according to RCA rector Professor Sir Christopher Frayling.

DESIGN RIGHTS:

• A common law intellectual property right which applies to original, non-commonplace designs for ten years from first marketing

• Any design meeting these criteria automatically carries design rights protection, without registration

• Registered design rights, handled by the Patent Office, run for up to 25 years

-

Post a comment