Forging ahead

Next month, the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Modernism blockbuster will showcase some of the most famous designs of all time. Hugh Pearman ponders the path of the era’s classic furniture, from its progressive origins to ubiquity today.

Next month, the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Modernism blockbuster will showcase some of the most famous designs of all time. Hugh Pearman ponders the path of the era’s classic furniture, from its progressive origins to ubiquity today

It’s strange to think that, back in the mid-1970s, Modern furniture was an expensive, cultish hobby, confined mostly to the designer classes. You would find Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen chairs and tables in wealthier architects’ offices, but, domestically, the whole ‘design classic’ thing was yet to take off. Year Zero for that phenomenon was 1975, when Zeev Aram – already established in London as a rare provider of Modern furniture, both to his own design and by others – obtained the licence to make and sell Eileen Gray furniture. Aram had effectively rediscovered Gray, then in her late 90s. Their collaboration turned out to be epochal. Modernist furniture, arguably, led to the revival of Modernist architecture.

Aram started his shop in the King’s Road in 1964 – just pre-Habitat – when you might have thought Modernism was quite the thing. Not so – he recalls London and the rest of the UK, at that time, as being a ‘Modern furniture desert’. Paradoxically, the enduring image of the 1960s in the UK is retro. Forget Mary Quant and miniskirts, this was also the time when the nation rediscovered Victoriana, when the Beatles affected the dress of an old-time military band and the ultra-chic fashion store Biba was more Busby Berkeley than Bauhaus.

Arid conditions for Modern furniture continued up to the mid-1980s, when more affordable replicas of the classic interwar 1930s pieces began to appear. The now over-familiar designs of Le Corbusier/Charlotte Perriand, Gray and the Bauhaus gang, including Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer, came crashing down in price. Some were reasonable quality, some were not, but they answered a market need.

In Britain, one of the first to see trade opportunities in the replica market was Sheridan Coakley of SCP, who had started in business by reconditioning British tubular-steel PEL chairs. Coakley quickly moved on to commissioning designs on his own account – Matthew Hilton, Jasper Morrison, Terence Woodgate and many others owe a lot to him – but the classic pieces remain in the SCP catalogue, having settled down in a mid-market position. Meanwhile, others have taken the low-cost route and there are now dozens of suppliers of cheap replicas of just about anything ‘classic’ – from Charles Rennie Mackintosh to Isamu Noguchi. This, understandably, irritates the companies holding the licence for ‘authentic’ designs, such as Aram or Vitra. But, in effect, the market has split. The famous companies get on by taking risks, introducing new blood and new designs faster than the copycats can handle. Vitra now also produces some of its classic designs – by the Eamses and Werner Panton – out of more affordable and eco-friendly materials than the original glass fibre and resin.

Rediscovered Modernist furniture has had an impact far wider than people’s living-rooms. Architecture, once it had emerged from the recession of the early 1990s and the Postmodern decade that preceded it, looked for inspiration to the interwar ‘heroic’ period of Modernism. By then, the furniture of that time was back in production and even affordable. What was more natural than to create the interiors to suit that furniture? Where an architect such as Rick Mather – always a Modern furniture buff – had earlier designed his own furniture in the Bauhaus manner, to equip his 1930s-inspired bars and restaurants, the new generation of Modernists, who emerged in the 1990s, could buy for their clients off the shelf.

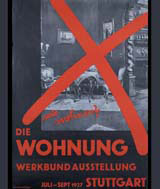

Thus the ideals of the Bauhaus, of all those who admired and copied the Bauhaus, and those predecessors, such as William Morris, who never quite got good, plain design down to a cost the masses could afford, finally came to be realised. Because the machine aesthetic of interwar steel-and-leather furniture was, at the time, a bit of a sham. It looked mass-produced, but wasn’t. Pieces were often individually made for individual houses – such as Gray’s E1027 table, or Mies’ Brno chair – and were never intended for wider distribution. The famous Mies Barcelona chair, of course, was for his German Pavilion at the 1929 Spanish Expo, intended only for the King and Queen to perch on as they toured around. They never sat down, but the building somehow needed those chairs to be complete.

So there is an irony in the fact that it is the cheap-replica merchants who have finally achieved the mass-production goal that this kind of furniture always implied. Today, no advertisement for an aspirational ‘loft’ apartment is complete without its Corbusier/Perriand chaise. It’s easy to sneer, but think how far we’ve come. These things are now accepted as everyday, as are the Modern interiors made to house them. Isn’t that a good thing?

Fashion had a big a part to play. Never mind the 1930s, it’s the 1950s and 1960s (in its Modernist rather than retro aspects) that have driven much interior design and architecture for the past few years. Almost every style magazine had converted to Modernism by the mid 1990s, and that was made easier by the blossoming of contemporary furniture shops, which were only too willing to loan their stock for shoots. It became a three-way, symbiotic relationship between architect, magazine stylist, and furniture supplier. It is in the way of things that this cycle will end – after a decade or more, it is already ending.

The elite will always want something different from the herd. Which is why, now, even chavs are buying £75 Eileen Gray knock-offs – the smart money, for the smart set, is on the fledgling Postmodern revival. But good design is good design – Eames chairs will never go away, any more than houses inspired by the Californian ‘Case Study’ houses of the 1950s and 1960s, which those chairs fit so perfectly, will go away.

It is hard to tell the difference in design intent between furniture and architecture sometimes – especially when designers turn their hands to both. But there are some indicators. For instance, while Le Corbusier’s buildings were famously influenced by aeroplanes and ocean liners, his and Perriand’s famous, and now oh-so-clichéd chaise took its cue from something a lot more pop – cheesy westerns. Cowboys with their feet up on the bar and their horses hitched to a rail outside – hence the pony-skin and straps of the original (and still available) version. But the matter of whether Le Corbusier was the first Postmodernist must wait for another day.

Modernism: Designing a New World runs from 6 April to 23 July at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7

-

Post a comment