Material gain

Textiles are now so sophisticated that they can react to their surroundings, or they can be engineered to provide a distinctive look and feel, which is creating tactile branding opportunities, explains Chris Lefteri

Textiles are now so sophisticated that they can react to their surroundings, or they can be engineered to provide a distinctive look and feel, which is creating tactile branding opportunities, explains Chris Lefteri

It says a lot about our new-found romance with materials that the term smart surfaces is even worth writing about. Until recently, the notion that a surface was anything but ‘the location of the points where an object’s material ends and the surrounding ambient begins’, as Ezio Manzini puts it in Materials of Invention, was unusual. But the 20 years since Manzini wrote this masterwork may as well be 1000 years ago, given the accelerating developments in technology.

Until recently, any discussion of surface was downgraded to a secondary role within the function of materials and objects. The surface was an area that carried ‘graphic signs of symbolic expression’, to quote Manzini again. Today, with new technology in materials driving a novel set of design possibilities, a product’s skin is perfectly placed to have a new central role, providing a completely new form of expression and function. Symbolic expression has been replaced by a functional expression. This is driving new functions and experiences in all areas of design, from oxygen-scavenging impregnated PET bottles in packaging to the ultra-cool view control screens in Prada changing rooms, which switch from opaque to clear, through to a new breed of vitamin-infused wearable fabrics that allow your body to absorb nutrition through your underwear.

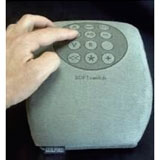

The surface of the object has become the driver for countless new consumer experiences, offering those moments of magic that technology is so good at providing. Sure, the surface still provides the opportunity for decoration and branding. But the type of branding we are talking about here is no longer just a case of passive graphic representation, but an opportunity to stimulate the user with his or her technology fix. Take, for instance, the touch-sensitive circular interface of the iPod.

In terms of the design process, this romance we are experiencing with materials marks a completely new departure, because in this relationship designers have virtually no direct physical contact with the palette of materials they are exploring. It is a relationship not based on craft, but on the latent experience that these types of material can offer.

Eleksen’s smart fabric interfaces were one of the first major smart-surface technologies to make it into the mass consumer market. But since its programmable fabric was first applied to a flexible PDA keypad, other smart surfaces have been finding their way into the designer’s toolbox.

At the heart of many of these new skins is smart technology, an area of material science that is defined by cause and effect or the reaction that occurs when a material is stimulated. The UK is providing a fair share of research into these new technologies, which exploit all sorts of functional requirements to enhance the user experience. If we narrow our field of view even further and stick to the area of techno textiles, we can see the rapid introduction of technologies across a range of industries.

P2i, a spin-off company from the Ministry of Defence, recently demonstrated at a Design Council workshop how plasma technology can be used to treat any fabric to form an invisible mask that makes it impermeable to liquids.

Then there are smart technologies, such as Peratech’s unique type of sensing material. This reacts to pressure to such a degree that it transforms itself from a perfect insulator to a conductive material when you push it. Processed as a pill form or as fabric, the technology has massive potential to be applied in a huge range of industries, from the under-the-surface functionality of the electronics industry through to the automotive industry, where non-sparking contacts to seating fabrics could detect the weight and position of a passenger to differentiate between a child and adult, and whether to activate air bags. Alternatively, the material can be used on the bumper to trigger car bonnets to raise at the most appropriate speed, depending on the type of impact. In this scenario, the sensors can detect the difference between a hard or soft impact and the degree to which the bonnet should raise up.

Smart surfaces have established their own values and spawned a science independent of the substance on which they are based, offering all areas of design surfaces that are expressive, reactive and intelligent – and anything but superficial.

Chris Lefteri is curator of 100% Materials, which runs from 21 to 24 September at Earls Court 1, London SW5

-

Post a comment