Fowl play

Chicken Run was backed by Dreamworks; Brian Sibley wrote a book about the shoot. Is Aardman about to hatch a blockbuster?

It all started 30 years ago in Nick Park’s back yard in Preston. There were these three chickens called Martha, Clara and Penny. They were never meant to be eaten, rather kept as pets.

“My sister and I used to lure them into the house and make up stories about them,” recalls Park. Some of these stories have now found their way into Chicken Run, the most ambitious film yet by the creator of Wallace and Gromit. To be more accurate, it’s the biggest undertaking so far for Aardman Animations, which produced those exquisitely funny half-hour, Oscar-winning classics The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave.

This new film is Aardman’s first feature-length production. It is backed by Steven Spielberg’s Dreamworks, co-directed by Park and Peter Lord, and it took three years to make.

The $30m (£20m) budget on Chicken Run – it cost £1.3m to make A Close Shave – plus Hollywood backing in the form of marketing and promotion, puts Aardman in a different league. The filmmakers are now in competition with market leader Disney (Aardman turned down Disney’s offer to back Chicken Run).

It’s a classic tale of small time hitting big time, with all the attendant nervousness and apprehension. The only indication so far that Chicken Run will be as universally acclaimed as its Oscar-winning forerunners is a single rough-cut preview in Portland, US, where the audience gave the film – a sort of chicken-ised Great Escape set on a bleak Yorkshire poultry farm in the 1950s – a standing ovation.

Back at their sprawling Bristol studios, Nick Park and Peter Lord turn out to be every bit as quirky, self-deprecating and characteristically English as you would wish the creators of Wallace and Gromit (Park) and Morph (Lord) to be. Wasn’t it difficult for Park, whose attention to detail borders on the psychotic, to play overseer on a project that, at its height, required 30 separate working units?

“It’s been a huge challenge for me to direct more and do less. Peter and I designed the characters and did some of the storyboarding, but apart from that it’s been a matter of keeping all the plates spinning at once. The pressure has been relentless… every second has been accounted for… there hasn’t really been time to miss being hands on. Peter is better than I am at seeing what other people can bring to it. I tend to think it would be simpler to do it myself. The biggest challenge has been telling a longer, more complicated story,” says Park.

According to Lord, “In the first few months we were madly concerned about the minutiae of what the animators were up to, but as time went on, we were able to take their expertise for granted. Even so, you still find yourself worrying about the most ridiculous things,” Park adds, “That’s what’s exhausting – trying to balance the details with the overall picture.”

The balancing act is especially difficult when you’ve entrusted your baby’s upbringing to a whole team of carers. Both Park and Lord are not only intensely creative, but their previous work has been characterised by a very singular vision. Only Park, whom many regard as a genius, could have made the Wallace and Gromit films; only Lord could have made Wat’s Pig, Oscar-nominated in 1996, the year after A Close Shave’s triumph.

Aardman was already well established on the British animation scene when Park joined it in 1986, fresh out of the National Film and TV School, with a half-finished graduation film in his pocket. The company was founded in the 1970s by Lord and an old schoolfriend, Dave Sproxton, who progressed from experimenting with chalk figures on the kitchen table to selling a fairly conventional piece of animation about an unlikely superhero called Aardman to the BBC for £15. They immediately opened a joint bank account, toying with the idea of calling themselves Dave and Pete Productions, but finally settled for Aardman Animations.

Apart from the long-running Morph, TV ads and music videos were the basis of Aardman’s early output, including videos for Nina Simone’s mid-1980s hit My Baby Just Cares For Me, and Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer. The turning point came when Channel 4 commissioned a series of animations, Lip Synch, in 1989.

Park was given a five-minute slot which emerged as Creature Comforts, in which zoo animals talked about their lives in captivity. It won the 1991 Oscar for Best Animated Short, and was taken up by the Electricity Board in a lucrative TV ad campaign. At the same time, Park was putting the finishing touches to A Grand Day Out, his graduation film, the original Wallace and Gromit adventure. It confirmed him as a filmmaker of rare originality and wit.

What chiefly distinguishes Aardman from its peers is that it works in 3D, using complicated sets, massive motion-controlled cameras resembling rocket launchers and, in the case of Chicken Run, a cast of many characters, each one lovingly built up around a basic metal armature. Since Chicken Run has taken 18 painstaking months to shoot – it’s a good day when there is as much as three seconds’ worth of celluloid in the can – the models have to be made to last. The heads and hands are still plasticine (the famous Aardman Mix, blended on the premises in an old chewing gum machine), but the rest is now made from a more resilient silicon material that can withstand frequent man-handling by the animators.

Even so, a maintenance team is constantly on call to deal with cracking, splitting and feather fatigue. If you saw the things these chickens get up to, you’d appreciate the problem. By comparison, Steve McQueen had it easy in The Great Escape.

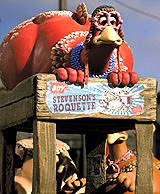

On the day of my visit to the Aardman studios, they’re shooting the final scene, involving a huge pie-making machine acquired by Mrs Tweedy, the villain of the piece, with voice by Miranda Richardson, who has every intention of recycling her poultry stock into chicken pies. Like Park’s sheep-shearing contraption in A Close Shave, the pie-making machine is an intricately constructed miracle of Victorian technology, partly inspired by Park’s brief employment, in his youth, as a chicken pie factory worker. Rough storyboards are pasted on the wall and also fed into the editing machine to act as a template for the completed shots. I visited half a dozen units and, despite feeling as if you’re interrupting a team of biochemists on the brink of a major scientific breakthrough, the atmosphere is never less than convivial.

Taking the cue from Park and Lord, the crew has set its sights on excellence. As one of the senior animators, Ian Whitlock, called out to me as I was leaving his unit, “You can’t rush perfection, you know.” Art director Phil Lewis, who also worked on The Wrong Trousers and A Close Shave, is a slight, diffident character who happily admits, after nearly two years on one film, that “it’ll be nice to have other things going through my mind apart from chickens”.

Lewis says Chicken Run has been harder work than the previous films. “It’s very specialised work and we’ve all been on a huge learning curve. With the Wallace and Gromits we used cardboard cut-outs and storyboards at the pre-shooting stage. Now we design everything on computer first, which is a big time-saving development. We’re better equipped now than when we started Chicken Run,” he says.

The Dreamworks deal means that the commercial pressure – the marketing, the merchandising, the media circus – is taken off Aardman’s hands, so the creatives can stay focused.

Another four films will follow in this five-picture deal, including a feature-length Wallace and Gromit and Aardman’s next project, The Tortoise and the Hare.

Meanwhile, the world waits to see whether a bunch of rather dim chickens can put one over on Mickey Mouse.

Chicken Run opens all over the UK on 30 June. Brian Sibley’s book, The Making of Chicken Run, will be published by Abrahams to coincide with the film’s release

Don’t get even, get Angry

For a company that prides itself on old-fashioned modelling skills and family entertainment, Aardman’s newest creation, Angry Kid, comes as something of a surprise.

Not only is Angry Kid ‘definitely not suitable for family viewing’, according to head of productions Michael Rose, but it is available to view free on the Internet. This is a first for Aardman… and indeed for the animation industry as a whole.

The adventures of Angry Kid, unfolding in 25 weekly episodes, are available to all at www.atomfilms.com. Each episode takes approximately six minutes to download.

Created by Darren Walsh at Aardman’s studios in Bristol, Angry Kid is a vulgar, pre-teen street yob who comes from a dysfunctional family and is well known to his local police force. He is so objectionable and out of control, his dad wants to put him in a children’s home. He makes Harry Enfield’s Kevin look almost angelic.

In one episode he suffers a freak cycling accident that leaves a bone sticking out of his arm, to the delight of a passing dog. The series took two years to make at a cost of £450 000 and is being distributed by AtomFilms.

This American-based company, formed in 1998, markets and distributes what they call ‘short form entertainment’ to a worldwide audience. It is particularly keen on supporting independent film-makers and animators.

‘By releasing Angry Kid on the Internet, a potential audience of hundreds of millions across the world can enjoy each episode the moment it is released,’ says AtomFilms boss Michael Comish. Unusually, Aardman, despite being the producer of Angry Kid, will receive no fee from AtomFilms. Instead it is counting on profits derived from spin-off merchandise sales.

Wallace and Gromit, by far Aardman’s biggest money-spinner, has generated merchandise sales in excess of £150m in the UK alone. Clearly the company is taking a risk here, since it is impossible to predict how Angry Kid will be received. But the income accrued from the Wallace and Gromit films, plus the £156m backing from Dreamworks, has given Aardman the chutzpah to take a chance. Now one of Britain’s biggest film producers, it is operating on a global scale with the confidence to match.

The timing couldn’t be better. In the US, top directors like David Lynch (Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks) and Tim Burton (Batman, James and the Giant Peach) are working on shorts for the Internet, while the producers of The Simpsons and South Park also see it as the way ahead.

Quantum Project, the first made-to-measure movie for the Internet, premiered earlier this month. It was made by Eugenio Zanetti, production designer on The Haunting and Last Action Hero, among others. Mixing live action with 3D computer effects, Quantum Project is about a scientist, played by Stephen Dorff, who uses the laws of quantum physics to create the perfect girlfriend. The film also stars John Cleese as a drunken software pioneer.

The number of people downloading films to their TV is expected to rise in the next few years as broadband technology becomes available.

-

Post a comment