A second glance

Whether it’s graphic design or writing, showing your work to a fresh pair of eyes is a crucial safeguard. David Bernstein reflects on some near misses

I received a mailing this week from the National Theatre, a booking form for a production of a lesser-known Harold Pinter play. Within minutes I rang the theatre. Now the National isn’t one theatre but three. Hanging on, I re-read the mailing. It didn’t specify which theatre – Olivier, Lyttelton or Cottesloe. Each has its own character and seating plan, respectively in-the-round, proscenium arch and what I call workshop. It helps to know which.

I wondered how such an omission could have happened. Was it a deliberate Pinteresque blank for the spectator to fill in? Surely not. An accident then that nobody spotted. Which leads me to presume that the mailing had been produced in-house: when the client is also the writer/designer, that sort of mistake can easily happen. Lacking an objective eye, we see what we expect to see. Familiarity breeds content. That’s why publishers employ proof-readers. And why authors need editors, irrespective of the fact that, in another context, they may themselves excel at editing.

Did the 2012 Olympics logo originally omit the word London? In the final version the place name does look like an afterthought. ‘Ken Livingstone’s office has declined to comment on reports that the word London was only added to the completed logo at the Mayor’s insistence’ (DW 14 June). Presumably, everyone working on the project – the London 2012 Organising Committee and the team at Wolff Olins – was familiar with the location. Furthermore, Wolff Olins didn’t want to do the obvious. As its executive creative director, Patrick Cox, remarked, ‘It was never going to be a picture of somebody vaulting Tower Bridge’ (DW 21 June).

But there is a difference between doing the obvious and incorporating an obvious, but necessary, component imaginatively. It can be costly when the obvious is omitted.

My company helped launch a magazine for custom car enthusiasts. It was called Street Machine. Our young team, enthusiasts both, devised an exciting commercial featuring a typical custom car, heavy metal music and appropriate effects. The brand name, this being a launch, was well to the fore. We viewed the rough edit. All seemed fine till someone, who had in no way been involved, asked, ‘What is it?’.

‘What do you mean? It’s a magazine?’

‘Oh. I thought it might have been a car.’

The naked emperor and his courtiers couldn’t have been more embarrassed. We ran it again. Sure enough the word magazine wasn’t on the track and the front cover shot was taken up with the car. Which of the two – magazine or car – was the Street Machine?

Luckily, we caught it in time to make some adjustments. Someone had asked the obvious question. It – or something similar – is asked every night. ‘What’s that for?’ ‘What was that about?’ ‘Is it for a perfume?’ The reason for the incomprehension is nearly always the fault of which we were guilty – letting the metaphor upstage the brand.

The metaphor, whether image or artefact, is more interesting than the brand with which it is associated. The celebrity is more glamorous than the product being endorsed, the handsome, young racing driver more thrilling than the bank. Little wonder that the metaphor takes over. But to allow it to usurp the identity of the brand is an act of betrayal. Which, for some of us, brings us back to Pinter.

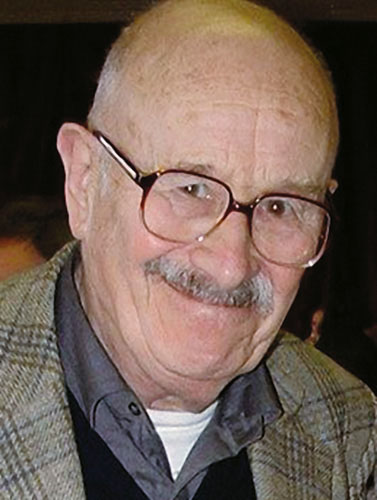

David Bernstein

-

Post a comment