Breaking out of the mould

Own-label packaging is big business, but creative judges say that it has lost its spark. Richard Clayton finds out whether the inspiration is still there

There was a time when own-label meant cheap and cheerful. All that changed when retailers realised shoppers weren’t influenced by price alone and started to trade off their corporate brands and develop more sophisticated lines in addition to budget offers.

During the 1990s own-label products began to behave like manufacturers’ brands, with sub-brands, price points and segmentation, says Design Bridge managing director, branding and packaging Jill Marshall.

Parker Williams creative director Tamara Williams, who works extensively with Sainsbury’s, believes own-label has grown up.

‘Instead of being a series of quirky jobs, they’re brands in their own right. Sometimes, particularly in ready-meals, they’re category leaders. Where once own-label was considered the poor man, now it’s creating category rules, not following them,’ she says.

Own-label now accounts for more than 45 per cent of sales in the UK grocery market (source: Datamonitor, August 2001) and most retailers operate a tiering system of good-better-best. It is similarly entrenched in the toiletries market.

To create a convincing own-label brand you need to differentiate through product quality and a story that can link the pack with the retailer’s values. Sainsbury’s has done this well with Be Good to Yourself, Taste the Difference and Blue Parrot Café, Marshall believes.

In general, however, concerns are being raised about the distinctiveness of own-label packaging. The category yielded no winners at the Design Week Awards. The judges’ statement amounted to a reprimand, ‘some 70 to 80 per cent of entries didn’t hit the spot. [The design] is becoming very formularised and there is not a lot of originality. The idea is rarely carried through to conclusion and the detail is lacking’, it said.

Fair comment? One of the judges, Lippa Pearce design director Harry Pearce, explains. ‘The problem was we’d seen it all before. Historically, the precedent was set by [Pentagram partner] John McConnell’s work at Boots the Chemists. It raised own-brand above the level of the commodity into something of worth and dignity,’ he says.

Lewis Moberly creative director Mary Lewis, another Design Week judge and brand counsel to Marks & Spencer, believes own-brand packaging has lost the immediacy it had during the supermarket revolution of the early 1980s.

‘Own-brand used to be somewhere to look for new things. It was lively and exciting. Retailers were fast on their feet and brands were caught napping. But now the brands have got their act together and the own-brand ideas seem retrospective – things that were played out ten years ago,’ she says.

Marshall concurs. ‘There’s some nice stuff out there, but nothing that blows you’re socks off. Although nothing’s awful either,’ she says.

This implies some are happier to stick with the conventions rather than risk anything new. Given the pressure on products to perform on-shelf, it could be tempting to go with what’s tried and tested.

Boots, which Marshall also singles out for praise, is not resting on its laurels. Last week it unveiled the first evidence of Dew Gibbons’ revamp of the Essentials range, which combines clear packaging with a round-cornered rectangle shape and a natural matt cap (DW 25 April).

Superdrug also repositioned its Solait suncare range recently to make it more approachable (DW 4 April). Design team manager Neil Pedliham says own-label brands have suffered in retailers’ price wars, but denies they’ve reached a creative plateau.

‘[On the contrary] own-label has the potential to be the saviour of packaging design. I’d always encourage retailers to use ownlabel as an expression of brand values,’ he says.

Pedliham adds, ‘Look at the [branded] competition. It’s smothered in claims – with product brand and parent brand fighting for space. They’re running out of space for all the things they’ve had to put on there over the years. It’

s not considered until a brand manager says enough is enough. It’s design evolution by committee.’

Clearly much depends on the category and the consumers it is targeting, with commoditisation at one end of the scale and specialisation at the other. But how do designers get away from the generic?

Eschewing ‘me-too innovation’, Superdrug tries to make a statement about its offer. ‘There’s an instant idea behind Solait’s sun splat [a droplet of liquid rendered in gold foil]. Fun, sun, quality, family – one little symbol encapsulates a great idea. That’s the advantage of own-label – design is king,’ Pedliham says.

Lewis is less sure. She sees ‘dangerous similarities’ between what Boots and Superdrug are offering.

She adds, ‘Retailers [have] used design to make themselves more interesting and attractive, but they have not thought through branding.’ If retailer brands are to pass the ‘thumb test’ of covering up the logo, they must develop their own definitive look, Lewis believes.

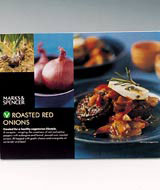

Marshall agrees. ‘Marks & Spencer is producing some beautiful stuff that really shows Lewis’s handwriting,’ she says. While one consultancy can’t handle a retailer’s entire business, guidelines for the ‘brand spirit’ are vital, she thinks.

Pearce says, ‘Nothing’s basic any more. There’s a constant need for change. Own-brand is a living thing that you need to tend the whole time.’

Retailers hold a wealth of information about consumers through loyalty schemes and get products to market rapidly. But their aggressive cost structures are also making it harder for larger consultancies to work with them.

The next stage for own-label design, therefore, could see more creative management of the kind McConnell and Lewis provide. Retailers might start looking for a leader of the pack to be their brand guardian.

-

Post a comment