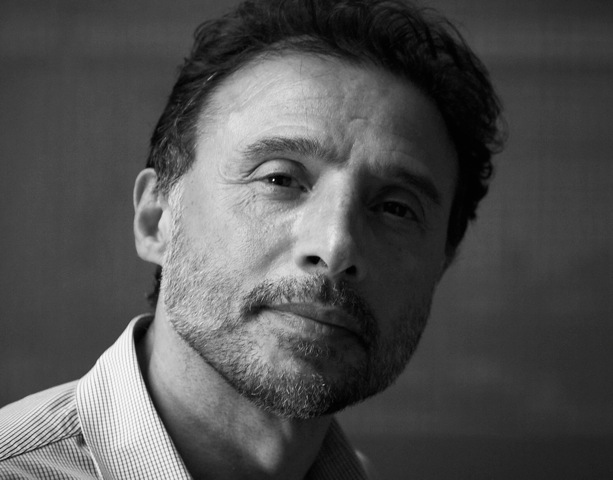

Pentagram’s Lorenzo Apicella on collaboration, British designers in the US and Mad Men

Pentagram’s San Francisco-based architectural partner has recently completed a Mad Men tribute project. We talk to him about how he works with other partners, how UK design is perceived on the West Coast and the constant strive for perfectionism.

“I’m surprised at how many English voices I hear on the streets and how many of them are designers,” says Pentagram’s San Francisco-based partner Lorenzo Apicella.

He adds: “British design is hugely well respected on the West Coast – we personally know many people who have come through Pentagram London who are now working for Apple for example – and from Apple there’s a diaspora that goes on to Google and Facebook and elsewhere.

“If you come through a good London design studio you can get recruited – it’s very noticeable on the West Coast at the moment as it’s such a vibrant place.”

Apicella moved from London to San Francisco in 2006 – a lifestyle decision, he says. Born in Italy, he studied architecture at the Royal College of Art and ran his own practice for around a decade before joining Pentagram in 1998. Alongside William Russell and Daniel Weil he is one of three current Pentagram partners who trained as an architect.

This week the Mad Men tribute bench – designed by Apicella alongside fellow Pentagram partners Michael Bierut and Emily Oberman, was unveiled in New York.

The bench was commissioned by TV network AMC and is inspired, Apicella says, by the practice of “Draping” – people taking selfies or posing for photographs in the style of Mad Men character Don Draper. “We wanted to make this into a real thing,” says Apicella.

While from the outside it might seem strange for a project like this to involve three senior Pentagram partners, Apicella says that in fact it is a “classic” example of how the consultancy can work collaboratively and bring different skills to bear.

“AMC is a client of Michael’s,” says Apicella. “They approached him and asked him to come up with ideas – any ideas – to promote the final series of Mad Men.

“He got together with Emily as she has a lot of experience in entertainment, and when they focused on the idea of a 3D intervention they got in touch with me.”

Apicella says: “Whenever a project feels like it would work across 2D and 3D we make the point [as Pentagram] that we can design for the project in all its manifestations and that we can do this without stretching different disciplines beyond what they can do.

“I think there are a lot of design consultancies who find themselves going across a lot of disciplines but might not be good at all of them – if a studio grows organically it can find itself stretching beyond its core discipline.”

Pentagram’s famous partner structure gives the consultancy an advantage in this respect, he says. Designers are invited to join the firm only when they have shown success in their own practice and when they sign up they must agree to share resources – but also income and equity.

Apicella says: “This method allows us to speculate and try people from different backgrounds – what unites them is that they’re extremely good at what they do.”

But in collaborative projects involving several partners, are there ever issues of ownership of territorialism? Apicella says not. “In the end [this Pentagram model] is what we subscribe to – and as long as everyone clearly understands what they have contributed it works.”

He implies as well the lengthy Pentagram selection process – in which all partners have to unanimously agree on a new recruit – can tend to result in a certain type of person joining. “We take our time with the process,” he says. “Any potential candidate has to be patient as well as talented – obviously it isn’t for everyone.”

As an architect often working in close proximity with designers from other disciplines, Apicella also has an insight into the attributes that unify and divide different types of creative work.

He says: “In Italy pretty much any designer – as I did – would go to architecture school and that would be the grounding for them to then specialise in graphics or product or any other discipline – and I think that that’s a testament to the fact that all design disciplines are closely connected and it’s rather an artificial thing to silo them separately.

“However, the reason they have been siloed is that there’s enough esoteric depth in each discipline to realise that you can’t do all of it equally well.”

However, the main thing that unites all designers, Apicella says, is an almost intangible drive for perfection.

He says: “I will fuss endlessly over an architectural plan and the aesthetic appeal of it, which is rather an esoteric concern. When I see a typographer really finessing the kerning on a piece of graphic design I know that those two things are really closely related and I understand that obsession about trying to make something perfect.

BESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswyBESbswy

“People who see [the final work] might not necessarily be able to define why it’s perfect – and I almost prefer when you don’t have to explain it for people to realise that it’s right.”

-

Post a comment