Remembering Ken Garland: “A man you quickly run out of words to describe”

Looking back at the life of the British graphic designer, writer and photographer whose work impacted not only the design industry but also education.

Ken Garland – whose designs spanned the world of toys to nuclear disarmament – was a “man you quickly run out of words to describe,” says Craig Oldham. Garland, whose political writing and influence have influenced generations of designers, has died at the age of 92. He is survived by his family and wife Wanda.

Garland was born in Southampton in 1929, raised in north Devon and later attended London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts in the 1950s. It was here that he studied alongside Alan Fletcher, Derek Birdsall and Colin Forbes. In 1962, he started his own studio, Ken Garland & Associates, which ran until 2009. The choice of trading name – Ken Garland & Associates: Designers – was to “signify that the outfit didn’t consist merely of one designer plus odd helpers who knocked off paste-ups, took phone messages or ran errands”, Garland wrote on the studio website.

“Those who worked with me between 1962 and 2009 have always been designers designing – no secretaries, no typists, no donkey-workers,” he added. There were never more than three designers at one point, but the studio worked with clients like the Science Museum, Barbour and Paramount Pictures. For Garland, “an increase in size would have meant fruitless to-ing and fro-ing, more unexplained and unacceptable overheads, and less fun”.

Design that will endure for “generations to come”

“As those who knew Ken, and those who knew of Ken, have tried to come to terms with the incalculable loss we’ve experienced, so many words have been said and almost all fall short of his character and his creativity,” Oldham says. Instead, Oldham believes that it is Garland’s varied work that will provide testimony to his creativity for “generations to come”.

Inspired by visits to Switzerland, Garland incorporated Swiss design into much of that work, including for Galt Toys, one of his most recognisable and admired projects. Though Galt was established over a century before as an educational product company, Garland was responsible for adding ‘Toys’ to the name and developing its new visual identity. A 20-year relationship followed between the designer and Galt Toys, during which Garland crafted wooden furniture, toys and board games including Connect.

Outside of the studio, Garland was a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and he redesigned the group’s peace sign symbol (originally created by Gerald Holtom when the CND started in 1958) into the graphic that is still used today. Garland would produce work for the CND throughout that decade, a period which saw a surge in popularity for unilateral disarmament in the UK.

The CND was not the designer’s only focus in the 60s. In 1963, he wrote the First Things First manifesto, which was published the following year in the Guardian. It was written as a response to the “apparatus of advertising” which Garland belieived put too great an emphasis on commercial work. Signed by 22 contemporaries such as Edward Wright and Caroline Rawlence, Garland proposed that the “the greatest time and effort of those working in the advertising industry are wasted on these trivial opportunities”.

Among these trivialities, he namechecked cat food, stomach powders, detergent and hair restorer. Garland suggested that a focus on instructional manuals, public signage and educational aids would redress this imbalance – what he called the “high pitched scream of consumer selling”. Garland was not calling for an end for commercial work, which he admitted would not be feasible, and the manifesto’s impact has endured.

“His principles and his politics are still the spine of the industry today,” Oldham says. In 1999, a second version was launched with signatories including Milton Glaser, Lucienne Roberts and Jonathan Barnbrook. First Things First 2000 took aim at an updated list of products, from credit cards to sneakers, in the hopes of renewing the spirit of Garland’s manifesto amid a rise of “uncontested” consumerism.

“He didn’t just see us as students, he saw us as individuals”

Olwen Moseley, professor and dean of Cardiff School of Art & Design, recalls the original manifesto’s influence when she was helping to structure the school’s BA in graphic communications in the 1980s. Garland paid an interest in the course’s developments, Moseley explains. “Our experience of him and First Things First gave us the confidence to develop a programme that gave aspiring graphic designers ambition and purpose in terms of their place in the world,” Moseley says. “If you’re in graphic design, it’s all too easy to be seen as an execution service of making things look good, as opposed to participating in the problem solving.”

Garland was a regular visitor and friend to the school over the years, according to Moseley. “For someone who was such an activist, he was always gentle and quiet about his influence,” she adds, noting his interest in the students’ lives and work. Moseley pinpoints Garland’s “distinctive persona” – as well as his signature hats – in her memories of the designer. “He made people feel like they he had time for them,” she says. “He was interested in people.” Oldham echoes this, adding that Garland “always wore a welcoming face”.

“My last memory of him was surrounded by a group of students at a design conference – listening to them, chatting to them, being present for them,” Moseley says. Garland was a lecturer throughout his career, including posts at the University of Reading and the Royal College of Art. And of the many tributes to Garland on social media, many designers mention his mentorship during their early days. One such student is Stuart Williams, a graphic designer now based in Finland, who first met Garland in 2014 when he was a student at the University of Chester. Williams was part of a student collective that reached out to Garland to lecture at the campus. But before he agreed to come, Garland invited the students to his home in north London.

“I was so shocked to just go around his house and the studio area and see the sheer breadth of design work he’d done,” Williams says, among them his Galt toys and walls full of posters. “You feel like a blip on the radar in comparison to the amount of stuff he’d done.” The following month, Garland travelled north to speak at the university, handing students pebbles as they arrived at the lecture. “Just like a pebble, every single one of them is different,” Garland told the students. “And so are you.”

That resonated with Williams, who adds: “He didn’t just see us as students, he saw us as individuals.” The lecture was a moment for Garland to reminiscence on his career, Williams believes, and he made frequent reference to photography, one of his less discussed talents. As well as regaling the students with tales from his career – once more stressing that he hired designers, not assistants – Garland joined the students for lunch and then drinks afterwards, bringing with him an original Galt chair to the student bar. Garland’s willingness to get a drink is echoed by both Moseley and Oldham. “He got us drunk,” Williams says, “and killed us laughing.”

When Williams moved to London, and was in the early days of his career, he sought out Garland once more for career advice. The young designer had to choose between two internships and thought that Ken was the “perfect person” to talk it through with. Garland’s advice – “to focus on what would make you happy” – was simple but effective, Williams says.

“Playful, mischievous, vibrant”

Craig Oldham adds a variation to this lecture story, which speaks to Garland’s wry sense of humour. While talking at Cheltenham Design Festival, Garland again handed out pebbles to the audience to make a point about uniqueness and character. One woman arrived late, Oldham recalls, and Garland returned to his bag to hand her another pebble. She thanked Garland and raised her hand to her mouth.

“Ken looked on shocked as that smooth little stone started its way south – she thought this lovely man had handed her a sweetie,” Oldham says. “Ken, in his charming wit, politely asked her to return the pebble, regardless of its exit point.”

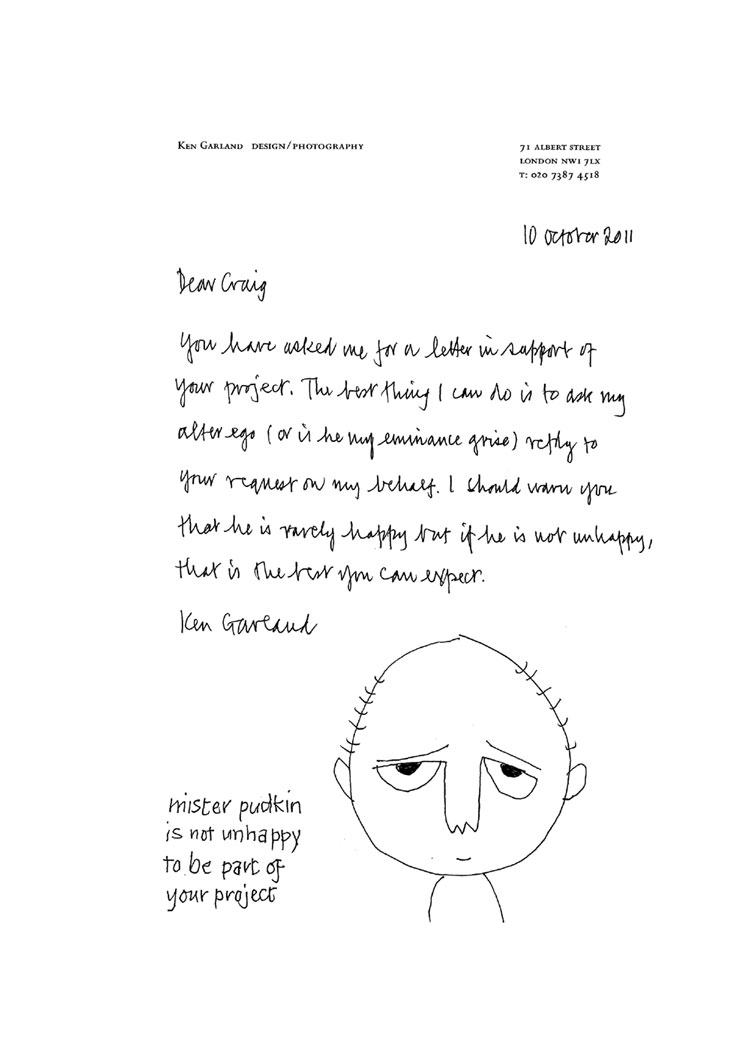

Later that evening, Oldham explains that they laughed about ‘Pebble-gate’ and listened to Garland’s stories. “I was overwhelmed when he took out his little bag again (in the middle of a pub in the middle of the night) and handed me a small brown stone,” Oldham recalls. Garland said that he could keep the pebble, adding that “Mister Pudkin is not unhappy for you to have it.” ‘Mister Pudkin’ was one of Garland’s alter-egos – usually seen as a doodle on Garland’s personal artworks and letters.

“His classes, lectures, workshops and courses saw countless designers in their most formative years inspired and impacted by one of the industry’s best,” Oldham says. “But for me the work he did for Galt Toys personified the person best – playful, mischievous, vibrant. That’s how I remember Ken.”

The banner and credited images are courtesy of publishers Unit Editions who have made the monograph of Garland’s work free to download as a PDF.

-

Post a comment