Mixed messages

Oliver Bennett looks at the nominees for this year’s Beck’s Futures award, an exhibition that seems to be singlehandedly maintaining the ICA’s provocative reputation

You’ve got to hand it to the Institute of Contemporary Arts. Whatever you think of its Beck’s Futures award – now in its fifth year – the prize has had the required effect of bringing the multi-purpose gallery-cum-culture lab back into the visual arts spotlight.

Back in 1997 when the gallery should have been enjoying its 50th birthday year, the organisation was considered to be in such dire straits that the Guardian ran a feature headlined: ‘Will the last one out of the ICA please turn off the lights?’ Ten years before that, in 1987, the Guardian (again) decided that the ICA had ‘become a playground for a declining civilisation’. It had become increasingly marginal, argued the critics, and hadn’t led from the front in the way that it should.

But the ICA has long been at the receiving end of hard knocks from conservatives and liberal art critics, and has managed to adapt and survive. Indeed, it’s one of those places that seems to exist in a permanent state of crisis, constantly in search of new audiences. Because of this – and in spite of its periodic troughs – new generations are continually coming into the ICA, and the Beck’s Futures Prize has been a catalyst in helping to place the organisation back in pole position as a centre for the experimental, the avant-garde, or to use the contemporary cliché, the ‘cutting edge’.

Even so, you might say the show is a bit of a puzzle. It’s always hard to divine a central theme, making it somewhat of a portfolio event, without singular thrust or purpose. Adding to the confusion is the fact that it features a full ten nominees, which rewards more people than the Turner Prize’s annual quartet (the £65 000 prize fund includes £25 000 for the winner and £40 000 to be shared among the shortlisted artists) but inevitably loses out on gladiatorial impact. Nor does Beck’s Futures make much attempt to apprehend the state of the art: ICA director Phillip Dodd says that ‘it obeys no orthodoxy’. Fine, except that in retaining this marginal ethos, it loses out on a sense of identity – although it is often called ‘hip’, whatever that devalued coinage means these days.

The selection criteria also seems somewhat vague. One critic has put it that ‘Beck’s sees to the younger, untested end of the art spectrum’, and yet this year’s shortlist features only one artist under 30, and three over 40 – although it’s true to say they are not established, as such. ‘I think Beck’s Futures fills the necessary role of giving profile to people who aren’t already names,’ says Dodd.

If finding less well-known artists has become part of the Beck’s ethos, another aspect is its regional character. In the past, it has featured several artists from Scotland and three of the past four winners were based in Glasgow, while this year the shortlist includes contenders from Glasgow, Liverpool, Belfast and also a clutch who have come to work in the UK from overseas. ‘We have young artists from Turkey and the Netherlands, Bulgaria and Brazil, who have chosen to come and work in Britain and remind us that British art has always been enriched by migrants,’ says Dodd, which is appropriate, given that when the ICA was founded it was hoped that it would end British artistic isolation.

There’s always a few nice surprises in Beck’s Futures. Among this year’s nominees is Susan Philipsz, for instance, who performs cover versions of songs in unusual environments. She’s belted out a Velvet Underground song across the Tannoy in a Manchester Tesco Metro store; ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry’ in a bus station in San Antonio, Texas, and socialist anthem The Internationale in a public underpass in Slovenia. ‘What I’m interested in is bringing you back to the place you’re in, making you aware of your environment and your own sense of self,’ said Philipsz, who did an MA in Belfast. It reminds you of Gillian Wearing, who danced alone in a London shopping mall and recorded the results, and it’s the sort of idea that could be transposed to advertising – as indeed, have a few of Wearing’s ideas (to her chagrin).

Another artist in Beck’s Futures garnering a lot of interest is Tonico Lemos Auad, who has so far caused the largest newspaper stir for his playful idea of making sculptures out of carpet fluff, and drawing pictures on bananas. An ex-architecture student, Auad shows that drawing can be done with almost anything: in one show, he arranged a gold neck chain to resemble the outline of a dead body at a crime scene.

Last year in Beck’s Futures, it seemed as if there was a burgeoning political consciousness; more in the sense of a neo-Situationist tendency than agitprop. This still seems to be the case. Bulgarian video artist Ergin Cavusoglu shoots surveillance-style film of London streets, capturing images of parked cars, road signs and passers-by. It’s got a kind of Crimewatch Reconstruction grimness to it, and Cavusoglu has said that it may have been a legacy of growing up in communist Bulgaria ‘under a watchful eye’. Another who is making reference to the ever-fashionable themes of control, power and surveillance is Dutch artist Nicoline Van Harskamp, who is to bring real security guards into the ICA – possibly even a Hampstead Heath Ranger.

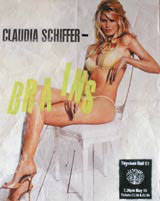

Yet it is somehow more exciting that the world of the trainspotter may be finally reclaimed from the anorak jibes and revivified as art. Andrew Cross, 42, has spent the past two decades photographing and filming trains and lorries, picking up on the hobby that he had as a child, and is to show a film that he made near Seattle. But perhaps the artist that Design Week readers will enjoy most is Simon Bedwell, a former member of art pranksters Bank, who paints parody posters, including one with Bob Marley promoting ‘Tate Jamaica’ and ‘Claudia Schiffer with Brains’. It’s an amusing use of the format that recalls the ‘subvertisements’ of Adbusters fame, and Bedwell’s work is to be shown in Piccadilly Circus Tube station as part of the show.

When Herbert Read co-founded the ICA in 1947, he described it as an ‘experimental workshop‚ and ‘an adult play-centre’. These two phrases certainly ring true when faced with this year’s contestants, and these factors make the sense of confusion that seem inherent in Beck’s Futures easier to bear.

Beck’s Futures 2004 runs from 26 March-16 May at ICA, The Mall, London SW1

The other contenders

Haluk Akakce This Turkish-born video artist projects light and floating forms, including petals and DNA helixes on to walls. Hallucinatory.

Saskia Olde-Wolbers The second Dutch-born artist in the show, Olde-Wolbers creates video installations filmed in intricate studio sets and narrated by a disembodied voice, to eerie effect.

Imogen Stidworthy Based in the soon-to-be culture capital of Liverpool, Stidworthy creates films with a strong language component. Here, she has made a film of two Cilla Black impersonators, to comment on the strangeness of performers who pretend to be someone else.

-

Post a comment