Show your true colours

An interior redesign at the Royal Commonwealth Society was a stylish way to communicate the organisation’s new strategy.

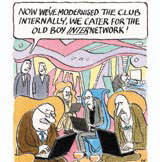

Is design central to an organisation’s strategy? The question was prompted one afternoon as I sat in the Commonwealth Club, ie the club of the Royal Commonwealth Society. What image do those words suggest? According to its chief executive, Stuart Mole, ‘comfortable leather armchairs and dozy afternoons’ – a fairly accurate description as recently as seven years ago.

Then everything changed. Dwindling finances dictated. Director General Sir David Thorne had long appreciated the inescapable logic of the club’s need to realise the capital value of its site off London’s Trafalgar Square, to sell the freehold and negotiate a leaseback. Only this way could the club fund a reinvention of itself for the 21st century.

In 1998 The Independent hailed the redesigned building as ‘the trendiest addition to London clubland since the Garrick in 1831’. It was, said another commentator, ‘one of the most brilliant and brave pieces of interior architecture in the capital in recent years’.

Bravery was essential, for the club recognised it was in danger of representing a vanished age, the glories of empire rather than the reality of a multicultural Commonwealth.

Rethinking and redesign had to go hand in hand. As Linda Morey Smith, the head of the winning architecture and design practice in a six-way pitch, recalls, Sir David Thorne crystallised the challenge with the words, ‘We’re a dying membership: we want people like you Linda to join the club’.

MoreySmith had 1400m2 to work with, barely a fifth of the original space. ‘This could have become just a smaller version of the old club,’ says Mole. ‘Instead, we chose to start with a new concept.’

Of course, certain links with the past had to remain, but it was necessary to re-express core values rather than enshrine the artefacts. Shields of Commonwealth countries displayed in corniches could not be incorporated, though a magnificent clock now has star billing in the new, light and free environment. The club imposes no formal dress code, though male members choose to flaunt the club tie, a multi-coloured swirl that echoes the interior design and logo and the multicultural and multi-ethnic nature of the Commonwealth. The graphics were immediately appropriated by the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, a timely endorsement of the new design.

Not everyone came on board so readily. Sir David had a council and members to convince. Some objectors were saying, in effect, that it was a London club and not a disco. But most of them realised that the design, the bright and cheerful ambience, was appropriate to the new vibrancy of the Commonwealth. Unfortunately, a few members left for other institutions. Others, though still retaining an affection for the old building, slowly began to identify with the change. Mole particularly cherishes a written compliment from the secretary of the Indian Army Association.

Mole wonders whether any other long-established (1868) London institution has done anything like it. He is convinced that the redesign has redefined how people look at the Commonwealth and how they regard the role of the RCS. Furthermore, it ‘has created a way in which we structure activities’.

Design is therefore not simply a reflection of change, but an instrument of change. Strategic thinking and design have acted symbiotically. The new environment has increased membership and changed its age profile. ‘A club,’ says Mole, ‘is a badge of identity.’ The Commonwealth Club’s identity is instantly conveyed to the visitor – unstuffy, democratic, eclectic, multicultural and at ease with itself. ‘There is buzz and flexibility. It used to be a haven – now you find a desire to engage,’ he adds.

And the food has improved. How could it not in this setting? It proudly boasts the London clubs’ Chef of the Year. He’s going to have a bigger and even better kitchen. This month work has started on an extension next door into what was a bank and before that a Turkish baths (as featured in Sherlock Holmes). MoreySmith is converting three floors, improving wheelchair access, accommodating an Internet access space, a business centre and a members-only lounge, separate from the functions area. The income generated by functions has helped to boost the club’s finances. So now, as Morey Smith says, ‘it’s time to give something back to the members’. Design and strategy will continue to work hand in hand.

Please e-mail comments for publication in the Letters section to lyndark@centaur.co.uk

-

Post a comment