The exhibition exploring the history of anti-war protest designs

The Imperial War Museum’s People Power: Fighting for Peace exhibition showcases everything from homemade protest banners to photomontage artworks dating from the First World War to the present day. Historian and exhibition curator Matt Brosnan picks out some of the most powerful anti-war designs from the past century.

With issues ranging from the rise of Donald Trump and right-wing populism to government cuts to the NHS currently dominating our TV screens and social media feeds, it is unsurprising that we have also seen greater numbers of the general public engaging with politics and protests in recent years.

The increased interest in the act of protest in its many forms – particularly marches and demonstrations – has also led to an outpouring of creativity on both a professional and personal level. The Anti-Trump march in London in February saw everything from emojis to flaming globe designs on people’s homemade placards, while Transport for London’s (TfL) London is Open campaign – launched last summer in response to the EU referendum result – commissioned designers including David Shrigley to produce a series of posters illustrating powerful messages of unity.

In light of this, the Imperial War Museum’s (IWM) new People Power: Fighting for Peace exhibition could not come at a more apt time. Working its way chronologically through the 20th and 21st centuries, the exhibition showcases the varied forms of creative expression used to campaign against conflict dating from the beginning of the First World War, right up to the present day.

Here is historian and IWM curator Matt Brosnan’s selection of the five most iconic anti-war designs seen in the exhibition.

A march of 2,000 anti-conscription protesters in London, 1939

“If there is one object that sums up the nature of anti-war protest, it is the placard. This simple hand-held device – used to convey a message while attending a demonstration – has always been at the heart of protest.

This photograph shows a march of 2,000 protesters in London in May 1939, their placards and sandwich-boards illustrating their opposition to conscription. It had been introduced for the first time in Britain in 1916, almost two years after the First World War broke out.

By contrast, Britain began to move towards conscription before the Second World War had started. When war was declared on Germany on 3 September 1939, full conscription was immediately imposed. Those of military age who opposed it could register as conscientious objectors (COs).”

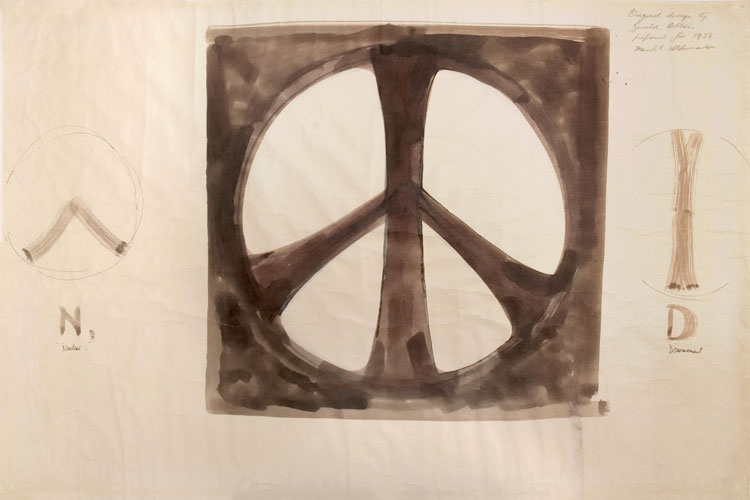

Original sketches by Gerald Holtom, 1958

“In late 1950s Britain, opposition to nuclear weapons began to galvanise large numbers. In 1958, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was launched and its first march took place, with protesters gathering outside Britain’s main nuclear weapons research facility in Aldermaston, Berkshire. This march was organised by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War.

As part of the planning, artist Gerald Holtom was tasked with designing a symbol to be brandished on banners and placards. As these original sketches show, the symbol he came up with was partly derived from the letters “n” and “d” in the semaphore alphabet, representing nuclear disarmament. It was quickly adopted by many groups of the anti-nuclear movement and has become iconic as a wider symbol of peace across the world.”

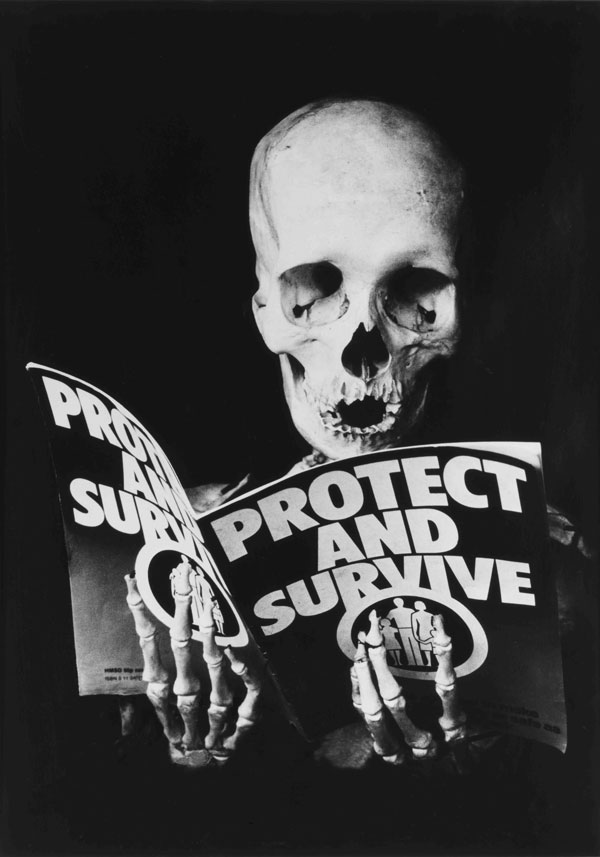

Protect and Survive, 1981, photomontage on paper

“This photomontage artwork, Protect and Survive (1980), is typical of the work of Peter Kennard, an artist who has become synonymous with protest. In the 1980s, Kennard worked with organisations including CND, the Labour Party and the Greater London Council.

He produced images like this one, which satirises the potentially futile advice on what to do in the event of a nuclear attack contained in the British Government’s pamphlet Protect and Survive.

The booklet was made available for public purchase in 1980 after its existence was leaked to the press. Its publication was reflective of the increased Cold War tensions of the time, when nuclear war seemed a not-so-distant possibility. This in turn led to a rise in anti-war protest.”

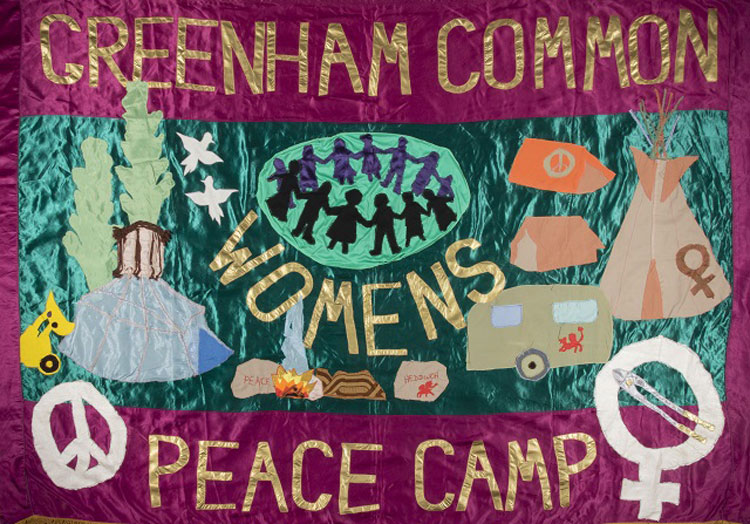

“Banners have acted as a visual and decorative element to anti-war protest over the decades. This one was made by Thalia Campbell, one of the original Women for Life on Earth, who first established a peace camp outside the perimeter fence at Greenham Common air base in September 1981.

The design references many of the elements of the peace camp, including the living conditions in tents and caravans, the human chains of protesters formed around the base and the strong feminist identity. Like many banners, it is also clearly and lovingly handmade.

The protest at Greenham lasted for 19 years and was originally inspired by the proposed arrival of US Cruise missiles on British soil, which led to a wave of protests in the 1980s.”

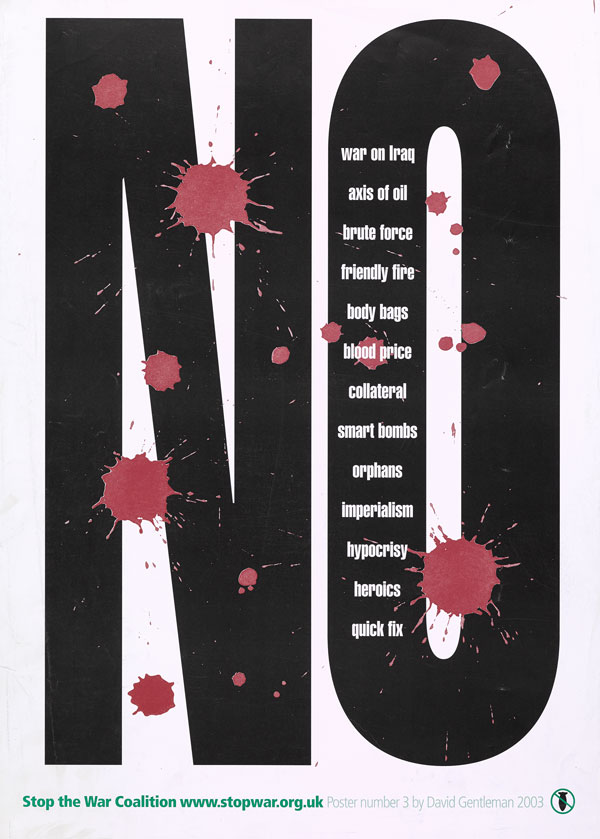

“In 2001 after the events of 9/11, the Stop the War Coalition was created in protest against the US-led War on Terror. The artist David Gentleman attended an early Stop the War demonstration in 2002 and was struck by the illegibility of many of the placards. He created a simple collage of “No” placards over a photocopy of a press photo of the demonstration, and submitted it to Stop the War who accepted the design.

As the group organised what was to become the biggest anti-war demonstration in British history on 15 February 2003, Gentleman designed an impactful “No” placard to be carried on the march. This is his preliminary design, incorporating a clear one-word message, an emotive blood spot motif and smaller-sized words including “collateral”, “friendly fire” and ‘body-bags’ within the larger “No”. He has designed many more placards and posters for Stop the War ever since.”

People Power: Fighting for Peace runs until 28 August 2017 at the Imperial War Museum, Lambeth Road, London SE1 6HZ. Tickets cost £10 for adults, and £7 for concessions and £5 for children. For more information, head to the Imperial War Museum’s site.

-

Post a comment