View finder

Oliver Bennett finds out more about the growing phenomenon of collecting photographs that have been discarded or lost by people and letting the viewer make up their own story about each image

The found photograph – the enigmatic picture located by chance in street, thrift store, office or attic – has quite a pedigree in the visual arts. Among the artists that have incorporated them into their work are Joseph Cornell, Gerhard Richter, Thomas Ruff and Christian Boltanski.

Now there’s a new wave of interest in found photographs on the Internet. Some sites are for fun, some for enlightenment: one is even there to reunite photographs with their owners. Whatever the reason, all revel in the chance aesthetic of the found photograph.

It also seems that some of the exhibitors are designers. Frederic Bonn, who is creative director at Euro RSCG in New York, made one of the best sites called Look At Me.

Appropriately, Bonn started his collection by chance. ‘I found a few photographs in the streets of Paris, became interested and started collecting them,’ he says. Now Bonn actively seeks photographs in flea markets and thrift stores, as well as keeping his eyes open on the pavement: primary source of ‘snaps trouves’.

Look At Me is also augmented by people who send in photographs: indeed, Bonn has had to install entry criteria: no personal pictures, no studio photographs, only photographs over 25 years old because ‘I was receiving so many of the wrong kind of photographs.’

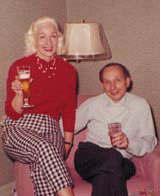

Bonn likes the way the pictures trigger imaginative ideas about the subjects’ lives, and likens them to the introduction of a story. ‘Somehow, they’re about memory,’ he says. ‘They feed the imagination. Also, as I only collect old ones, there’s every possibility that the subjects are dead, which is strange.’ There’s always the possibility of a curious serendipity, too. ‘For instance, I found a photograph two years ago of a couple in front of a Christmas tree,’ he says. ‘Later, I found another photograph in a different place. It was the very same people, a few years on.’

Most amateur snaps of people conform to the photographic vernacular: a centralised, face-on subject against a backdrop. ‘What is interesting is when they have made mistakesà like putting someone off-centre,’ says Bonn. ‘It looks as if it was planned.’ Which may be the reason why they were discarded in the first place.

Bonn gets a lot of requests from designers to use the photographs. ‘For instance, I’ve had two bands wanting to use a found photo from my collection on their CD covers. But I haven’t used them for commercial work. I think the essence of the photographs would change.’ More to the point, he thinks, is an interest from teachers looking to found photographs as starting points in creative writing classes.

What exactly is the charm of found photographs? Is it, as one critic has braved, that they mix nostalgia and Modernist distance? Netherlands-based photographer Astrid van Loo, who has created the website Time Tales together with Web designer Dick Dijkman, has thought a lot about their appeal. ‘It’s partly because we have all taken photographs like this,’ she says. ‘It’s the recognition of a shared experience that makes them attractive: somehow you recognise yourself in them.’

The found photographs tap into the collective memoryà she suggests, creating a history of the image in which everyone has participated. And they can carry an emotional charge. ‘For instance, when you see a photograph of a child taken by a parent, you can see the trust in the face. It’s entirely different from a press portrait, say.’

Her photographs, says the website, come ‘from streets and alleyways, fallen from bags or pocket, hidden compartment in cabinets or in abandoned houses’. Time Tales, then, is her ‘new home for lost photos.’ These are the waifs and strays of photographic reproduction.

Van Loo has collected found photographs for 15 years, put some on her personal website thus leading to Time Tales. Since then, she has been amazed by the interest. ‘People send photographs in: I’ve just been on holiday for two weeks, and when I returned there were 15 new photographs. Many people seem charmed by them. So what started as a webpage of beautiful, touching images became a small museum of lost lives captured on film from all over the world,’ she says.

She has no criteria for the photographs, other than rejecting anything obscene, illegal or uninteresting, and she groups the photographs into five date-bands from pre-1930 to 1990-present. ‘We show them as they were found, without suggestions – you should leave them open – just the finder, place and year,’ says Van Loo.

Others have used found photographs as a starting point for image manipulation. A couple of years ago photographer Christian Alderson, graphic designer Neil Edmundson and writer Jonathan Legender created Quality Control: The Art of Bad Photography, a Web exhibition that showed ‘an innovative and original exhibition of unwanted and neglected images, found and collected from friends, family, colleagues and in some cases, the pavement’.

‘Some were strange, abstract images that we blew up and exhibited. The point was that although they were rejects, they had an aesthetic quality,’ says Legender. He adds that their collection of mistakes also stands as a social document. ‘Family snaps are about pretence. These pictures are saying things aren’t perfect.’

Another with a collection of found photographs on the Internet is Damien Frost, who recently worked in London as a graphic designer and is now resident in Queensland, Australia. ‘I was given a photo album by a friend that she found on a bench,’ says Frost. ‘It belonged to an elderly man and contained pictures of his wife.’ Frost was fascinated by its air of sadness, added them to a few found photos he already had, and now has a dedicated section on his website.

Frost is interested in the dissociated personal charge of found photographs. ‘They have to have some sort of personal touch,’ he says. ‘There’s a lot of projection involved in looking at them, as if they’re an adopted memory.’ He says that he dramatises and even romanticises them. ‘Some have argued that it’s not what the artist intended to say, but what the viewer reads into it that gives an image its meaning,’ he says. ‘This project is driven by a similar philosophy.’ Their appeal, he adds, also lies in how they came to be lost or discarded.

Like Bonn, Frost has been asked by designers wanting to use them. ‘It’s interesting the way I’m approached is as if I “own” these images,’ he says. ‘Perhaps it’d be good to have a massive database where people can browse. I’m sure there are sticky copyright issues, but they were originally in the “public domain”, so to speak.’ Bonn agrees.

Frost now circulates his own photographs into the world. ‘When I pick up some holiday photos, if I don’t like a certain one I’ll stick it under a windscreen wiper, weave it into a fence, or leave it in those postcard racks in a café.’ It’s his way of giving something back to this lost photographic world.

FIND OUT MORE

Frederic Bonn’s site: www.moderna.org/lookatme

Astrid van Loo’s site: www.timetales.com

Damien Frost’s site: www.objectnotfound.net

Quality Control: The Art of Bad Photography: www.geocities.com/badphotography2001

OTHER FOUND PHOTOGRAPHY SITES

www.isthisyou.co.uk

www.kittyville.com/px.html

www.eighthforce.com

www.spillway.com

www.geocities.com/SoHo/1554/fopho.html

-

Post a comment