Design, Climate, Action: education is exploring new ways to teach sustainability

Leaders in design education are teaching a new generation how to think like sustainability innovators rather than designers.

When it comes to the climate crisis, there’s no right answer. As our Design, Climate, Action series highlights, designers are constantly adapting their work, often in reaction to new challenges or break-throughs. But how do you teach a new generation of designers about sustainability in an ever-changing environment?

“We’re comfortable being uncomfortable,” says Rebecca Wright, dean of academic programmes at Central Saint Martins (CSM). Across its art and design courses, the college has been rethinking its approach to the environment.

In some cases, this is about creating new classes. In 2019, CSM launched the Biodesign MA, which looks to incorporate biological principles into the design process. Later this year, it is starting the Regenerative Design MA – a partnership with luxury fashion corporation LVMH.

For existing courses, a key focus has been adjusting “learning outcomes”, Wright says. Expanding what constitutes a project’s success opens students’ minds to what is valuable. Success, she believes, can be calibrated according to values (such as social or climate issues) rather than simply aesthetics. One important frame of reference is the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

Links with industry partners also help students understand how their education can be applied in the real-world. This relationship works both ways too, Wright points out. In her role as D&AD president (the first academic to take up the role), Wright is also keen to foster the connection between a new generation of designers and industry on the New Blood and Shift programmes.

This approach doesn’t come without its difficulties. “The challenge for institutions like universities is that once you start prioritising these things, you quite rightly lay yourself open to criticism and evaluation from your own students,” Wright says. That list can be endless: how neccessary is it to travel to conferences? Is the printer ink environmentally friendly? The pandemic has provided some silver linings in this regard – virtual work has reduced the need for international travel, for example – though there will be more challenges.

For Wright, the key is to understand where change can happen both immediately and in the long term. “If we had the answers, we would know what we were doing,” Wright adds. “But we don’t have the answers to how we get through this. We are acquiring new knowledge the whole time.”

Teaching “sustainability literacy”

At Kingston University, a project for the Sustainable Design MA sheds light on an experimental approach to climate issues. Play on Sustainable Innovation comprises a deck of cards and products which ask questions about toy design – not only around manufacturing but also when it’s appropriate to raise environmental issues with children. As its mission statement sets out: “The paradox of toys is that they are threatening the futures of the children who play innocently with those toys.”

The project represents a more holistic – and literally more playful – approach to climate issues, according to course leader Dr Paul Micklethwaite. Micklethwaite took over the masters course ten years ago, and refigured it from a post-disciplinary perspective. Now, the course takes around 20 students from a wide range of backgrounds, from architecture to graphics and product design, who all want to “redirect that creative practice towards sustainability goals”. Often, they’ve been working in industry for a while.

Though the designers usually have an awareness of climate issues, a crucial lesson is “sustainability literacy”, Micklethwaite says. “Not just learning the facts and figures of memorising the UN’s SDG, but actually being able to apply sustainability knowledge and awareness through design practice.”

“The perfect sustainable outcome doesn’t really exist”

This is a broad concept, he admits, and it’s often impacted by the course’s make-up. A student from Latin America will have a very different understanding of sustainability than a student from India, he points out. Through lively classroom discussion, Micklethwaite encourages students to aspire to a sustainable ideal – while acknowledging that no one design can embody all the right approaches. As he sums up, “the perfect sustainable outcome doesn’t really exist.”

Teaching has also shifted on courses that don’t have sustainability in the title. Micklethwaite used to teach a 12-week module on undergraduate courses around sustainable issues – what he calls a “bolt-on” approach. But this has now been embedded on undergraduate design courses where work aims to address sustainability head on.

On a furniture course for example, there’s a brief called footprint, where students have to think about the impacts of their design decisions. It’s a partnership with architecture practice Foster + Partners. This forces students to think about “being a designer of materials, culture and physical objects”, Micklethwaite says.

Fostering “creative, playful exploration”

Not all of this is new, of course. At the Royal College of Art (RCA), the Innovation Design Engineering MA/MSc has been running for 40 years – a partnership with Imperial College London. A more recent offshoot is the Global Innovation Design MA. Professor Gareth Loudon heads up both courses, which aim to create a positive impact for people and planet. Sustainability is front-and-centre, he explains, and students usually fall into a few categories. Those who want to start their own business, those who want to join a design consultancy or design-led company, and those who want to stay in research or pursue further education.

Crucial to these two-year courses is a process of “creative, playful exploration”, Loudon says. As well as teaching day-to-day issues like time management and teamwork in a studio setting, the students are taught to become “comfortable with uncertainty”. That’s often harder for those from an engineering background, Loudon explains. Thorny issues relating to sustainability “aren’t as clear and nicely packaging as an engineering student might want”, he adds.

Teaching around sustainability has moved advanced greatly over the past decade, often in a more philosophical direction. Loudon compares it to his days of teaching product design, where sustainability would involve a consideration at the materials and assembly stage. It didn’t cover broader principles such as the circular economy or business models – which are equally important, according to Loudon. Like Micklethwaite, Loudon emphasises a post-disciplinary approach. “First and foremost, we’re creating innovators,” he says. “We’re not creating engineers or designers per se.”

“We actually want to make things positive”

One frustration for Loudon is the gap between the innovation on the courses and what’s happening in the industry. While terms like the circular economy are commonplace, not much has shifted in a business setting. One of the courses’ biggest impacts has been the start-ups that are disrupting traditional companies, he believes. “It’s hard to change a well-established organisation,” Loudon says, pointing to the notion of disruption innovation coined by academic Clayton Christensen. “It’s the upstarts that disrupt the incumbent.”

But no matter how good an idea is, it has to be supported practically. That requires training students in business and strategy as well as taking advantage of the technical prowess from Imperial College. Loudon has begun to see benefits of the courses: a valuable network between alumni and students. The dialogue informs the students about new approaches, technology, and provides business insights. Handily, it also means the creation of a new job network.

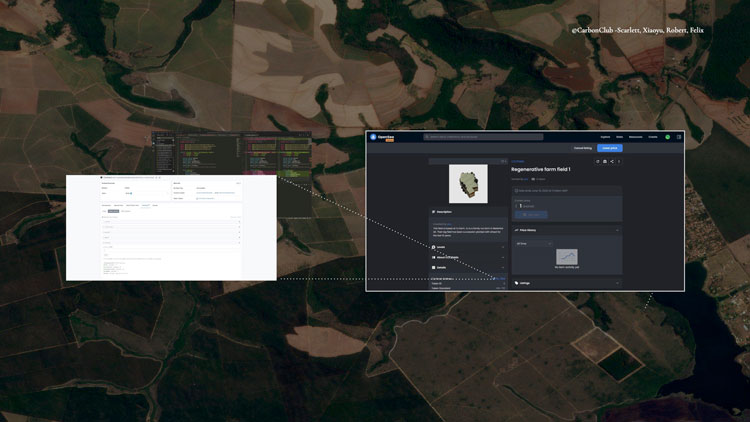

Despite the challenges, Loudon has a positive outlook. Many of the student projects have made the shortlist for the Terra Carta Design Lab, a climate initiative from Prince Charles and Jony Ive. One of those is Grounded Carbon, a platform which aims to streamline the soil-based carbon offsetting process. This solution epitomises a holistic approach – considering both carbon offsetting models and agricultural behaviour. It also represents a more forward-thinking approach to climate issues. “In the past sustainability has been about making things less bad,” Loudon says. “We actually want to make things positive.”

You can read more in our Design, Climate, Action series here.

The banner image is courtesy of the Royal College of Art.

Good initiatives in your article. This paper should add significantly and positively to the discussion: “Responsible Design is the Apex Design Mode to create our sustainable future” https://bit.ly/ResponsibleDesignIsApexDesignMode Recent peer-reviewed international conference paper for comment & collaboration. (shorter presentation https://youtu.be/HGlzw8XFQIo) from recent ISDRS conference. Do you think we should we continue to grow this work? There really are multiple angles from client / designer / field and context perspectives, this looks to be a valid tangent shift we will all benefit from acknowledging. Keep it simple to explain and follow the logic through to any level appropriate or possible.

See also: https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=AH%2FV015729%2F1