Take aim

Miriam Cadji targets Reconstruction, an exhibition about designers working in Britain from 1940-1951, to coincide with the Festival of Britain’s 50th anniversary

We may be teetering on the brink of a General Election, but the nation-at-large is suffering from a collective sense of “oh yeah, so what?”.

In today’s post-Cool Britannia-climate of apathy, contemporary design is ubiquitous – cynically used to brand the objects that surround us. Perhaps it is this complacent attitude that makes Reconstruction, the latest show to open at London’s Target Gallery, so compelling.

Held in this, the 50th anniversary year of the Festival of Britain, the exhibition focuses on designers working in Britain from 1940-1951, a decade when politics and design were inextricably linked. During the war, the Ministry of Information’s design department, headed up by architect Sir Misha Black and graphic designer Milner Gray, devised a highly sophisticated form of communication that both fed the propaganda machine and enhanced people’s everyday awareness of design.

After the war, it was important to sell Britain, both at home, where modern goods held the promise of a “bright new world”, and abroad, where the export drive was essential for economic recovery. All manufactured products suddenly had to have a design element, a radical concept at the time.

New ideas and aesthetics – which in the pre-war period were confined to an elite metropolitan circle of political and economic theorists, artists and designers – were finally pushed out to the provinces by the success of the Festival of Britain. Previously known as “commercial art”, after the festival the word “design” had seeped into the general vocabulary, eventually to become commonplace. As well as offering colour and optimism, there was a new democratic rigour descended directly from William Morris and the Bauhaus movement that was perfectly in line with the socialist ideology of the day, that brought with it the creation of the Welfare State.

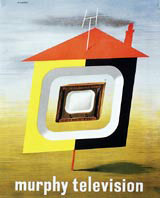

While Reconstruction aims to present the whole spectrum of design created in the period and includes ceramics, metalware, products and furniture, the bulk of the collection is given over to textile design and graphics (which includes book illustration, poster design and exhibition catalogues).

With its domestic scale, the gallery is an intimate space for such an ambitious show – there are about 100 objects in total on display – but curators Geoff Ryner and Richard Chamberlain are confident that, having staged a major exhibition of Robin and Lucienne Day’s work in 1999, this should be no problem. The show is peppered with gems, and among the highlights are a signed proof of the Festival of Britain catalogue cover by leading wartime graphic designer Abram Games, some gilded ceramic and glass brooches by potter Lucie Rie, and – the curators’ personal favourite – a reversible, wool shelter blanket with a morale-boosting propaganda motif by an unknown designer. Meanwhile, crowd-pleasers include Lucienne Day’s iconic 1951 Calyx fabric for Heal’s and an astonishingly forwardlooking acrylic portable radio, designed by Wells Coates in 1948.

Since the era was one of rich cross-disciplinary activity, the curators have resisted imposing boundaries by isolating the objects into obvious groups, or displaying them chronologically. A few items are on loan, but the bulk of the collection is for sale. Prices range from £15, for which you could pick up a book jacket designed by leading modernist graphic designer Enid Marks, to £5000, the estimated value of an armchair designed by architect Basil Spence in 1947.

Reconstruction, from 31 May until 30 June, at Target Gallery, 7 Windmill Street, London W1

-

Post a comment