Stage of the art

These days, stage-setting in London’s West End is far from a matter of relying on creaky props and painted backdrops. More and more set designers are turning to cutting-edge technology as the very basis of their designs, says Nick Smurthwaite

London’s West End may be stuck in a Victorian time warp, as regards its bricks and mortar, but when it comes to the technology used to realise stage design, things are definitely moving with the times.

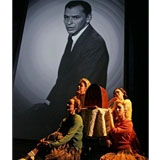

Sinatra, at the Palladium, resurrects the dead crooner in digitally remastered archive film, projected on to nine different-sized screens, the biggest of which rises up to 12m, while the musical Sunday in the Park with George, about to open at Wyndham’s Theatre, sees state-of-the-art video projection being deployed in place of traditional scenery, to recreate Georges-Pierre Seurat’s pointillist masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Both these shows are representative of the growing use of new technology and multimedia by stage designers. Projection has, of course, been used in stage design for many years, very often to evoke stormy skies or to interject some mock newsreel footage. The difference with Sunday in the Park with George is that it has been used as the very basis of the design concept.

So all-encompassing and ingenious is the design, drawing visual as well as narrative parallels between art and life, that you might imagine it would detract from the performance. Was that a concern for the director, Sam Buntrock, who also works in commercial graphics and animation?

‘Yes, at times, it was hard for the actors to feel they were not being upstaged by the design,’ he says. ‘My designer, David Farley, helped me to find an aesthetic in which the projections were part of the set, enhancing an environment, rather than a monkey on the actors’ backs. I wanted the actors to be inside the projections, not in front of them.’

Buntrock decided early on in the pre-production stage to use animation and projection to bring Seurat’s picture to life, and that the person to facilitate that was Timothy Bird, who co-runs the multimedia company Knifedge. ‘Tim and I were at the same school and, in fact, made some films together when we were about 15. He has an extraordinary ability to make digital content feel as if it’s been touched by hand, even though it comes out of a computer,’ he says.

For the UK premiere of Sunday in the Park with George, at the National Theatre in 1989, peripheral characters from the painting were represented by cardboard cut-outs. Buntrock and Bird have gone a step further by animating those characters and integrating them seamlessly into the cast of actors. Needless to say, the process was fraught with problems, both human and technical.

‘Of course, I felt I’d bitten off more than I could chew,’ says Bird. ‘The whole idea of projection design runs counter to the process of making a piece of theatre, where the rehearsal period is fluid and moves gradually towards its culmination. What happened here was that the director went into rehearsals knowing there were certain elements that were already locked into the process. What made a massive difference to my contribution was that Sam [Buntrock] really understands animation, which enabled us to go much further with it.’

Like Bird and Buntrock, Tom Pye, who designed Sinatra at the Palladium, has also worked in film and TV. Pye says he moved towards live performance because it offered more freedom of expression. He recently designed a modern-dress Measure for Measure, in which his use of electronic gadgetry enabled the actors to face upstage, away from the audience, while their faces were seen on CCTV monitors dotted around the stage.

Pye believes the availability of cheaper software is changing the way stage designers perceive their craft. ‘The scale of what was achieved in Sunday in the Park with George, on a fringe budget, would have been unheard of five years ago,’ he says. ‘It is important that we approach it from different directions. It’s like metal, wood and plastic – just another tool at our disposal. It’s how you use it that counts.’

By and large, it is the younger generation of stage designers who are pioneering the use of video projection and computer technology. But there are some notable exceptions, such as the much-respected William Dudley, whose work on Hitchcock Blonde (2003) and The Woman in White (2004) was bold, innovative and challenging.

In The Woman in White, Dudley dispensed with conventional sets altogether and opted for a kaleidoscope of projections to convey ‹ the story’s multiple settings, moving from baronial interiors to sunlit corn fields. The effect was cinematic and often beautiful, although the synchronisation of the projections with the live action wasn’t always perfect.

An unashamed evangelist for computer technology in stage design, Dudley does everything on-screen, including a virtual model of whatever set he is working on. The idea of not working on a 3D box model would fill most designers of his generation with horror. Dudley is used to fending off the Luddites, especially lighting designers, who prefer chunky wooden scenery to give them something to reflect off.

‘Young people can find the theatre very static and one of the things digital technology can do is to bring epic movement back to the theatre,’ says Dudley. ‘It’s like taking the audience through a big, animated computer game. I suppose we’re feeding off the effects-based film and computer game industries, but if it serves the theatre well, then that’s all for the good.’

All the designers were agreed that the technology must always be at the service of the play and the actors, not the other way round. Buntrock and Bird are keen to collaborate on another stage show using projection design, but only if it is something where the aesthetic and technical elements can be fully integrated. ‘I don’t want to use the technology as a short cut,’ says Buntrock. ‘There is a temptation to see projection as a veneer, rather than something integral to the whole. Sunday in the Park was perfect from that point of view, because it is all about the creation of the image.’

David Leveaux, who directed Sinatra at the Palladium, is equally wary of the dangers of technological overkill. ‘Theatre and multimedia are moving together, in some ways, but that doesn’t mean everything recommends itself to the same treatment. None of the technology makes sense unless it is channelled into something human. Technology, on its own, can’t make a show live and breathe,’ he says.

Sunday in the Park with George previews from 13 May at Wyndham’s Theatre, London WC2

-

Post a comment