Aide Memoire

Museum shops now offer visitors imaginative products that are a true souvenir of the experience.

Any habitué of the UK’s museums and galleries should have noticed that over the past ten years, the shop has become a vital part of the experience. No longer dusty repositories of long-unsold books, they now positively zing with gifts, objets d’art, household goods and curios, as well as the traditional gamut of mugs, pencils, erasers, postcards and posters.

Which must be why museum shops are having a period of upgrade frenzy. Herzog and de Meuron, the architect that first transformed Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern, is currently designing another shop for the gallery, set to open next spring. The National Gallery’s new shop, designed by Din Associates, opened last month in the gallery’s East Wing development. The Victoria & Albert Museum has scheduled a new shop to open next autumn, which is being designed by Eva Jiricna Architects, augmenting the extant shop designed by Jiricna in 2001. Meanwhile, product development and retail management posts have become an important part of the museum structure.

Merchandise is now being taken seriously and has found its figurehead. Kit Grover, a London designer, artist and illustrator has become the foremost designer of museum shopping, working most recently for Tate Modern, Gateshead’s Baltic Centre, the Hayward Gallery and the National Gallery.

‘I’ve been working in the area for five years, and I love it,’ says Grover. ‘What’s interesting is that London is setting the pace. Moma NY has had a design shop for decades, and everyone still thinks of it as the leading shop. But it doesn’t experiment like the London galleries, which are leading the way.’

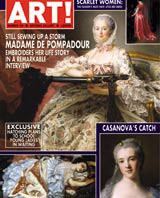

Grover has designed an exclusive range of merchandise for the National Gallery shop, based on the theme of Hello! magazine, substituting the word Art! in the magazine’s famous white-on-red logotype. ‘Luckily both the National Gallery and the magazine itself liked it,’ says Grover. ‘It’s saying that this is part of our culture. Everyone understands the graphic content immediately, and they see that the paintings are stories about people.’

The range covers address books to tea towels and playing cards, but while Grover may be experimenting with the merchandise theme, he is also pragmatic about people’s acquisitive impulses and desires. ‘It’s really important to realise that a lot of people like branded erasers,’ he says. ‘Yes, they are souvenirs, but I love souvenirs and ephemera. I think the drive to remember the experience is strong, which is why souvenirs have existed for about 200 years, about as long as the tourism industry itself.’

There remains concern among the more puristic end of the museum hierarchy that merchandise is a vulgar sell-out. ‘You do still find the type that only want to sell books and postcards, and considers merchandise to be the devil’s work,’ says Grover. ‘But as shops contribute so much to the exhibitions, these people are put in a weird position. They hate branded mugs, but like the funds they bring.’

Even so, Grover is trying to work on product designs that take the museum merchandise beyond the branded mug, as can be seen at his website, www.kitgrover.com. For instance, one of Grover’s first Tate successes was a Rubik’s Cube made in the style of a Gilbert and George photograph.

‘I noticed that both Rubik’s cubes and Gilbert and George photographs had the same modular appearance,’ he says. ‘It sold well, and what I liked about it was that it made you think about the work. I don’t like the products to be passive. Nor do I like them to be disrespectful.’ They have to be approved by the artists’ estates – in fact, some might even be designed by the artists themselves.

‘The Tate has elevated the idea of merchandise,’ says Grover. ‘It sells editions, artistic multiples and products by Fluxus [the early 1960s conceptual art movement, whose numbers included Yoko Ono]. Fluxus designed products for fake shops, so it makes sense to sell them in real shops.’ The Royal Academy shop has also sold artist’s editions and artist-designed merchandise such as ties and ceramics, and this approach has been adopted by smaller galleries, including the Serpentine and Whitechapel Galleries.

At their most corporate, museum products are part of the branding process, reflecting the visitor’s identification with the museum. ‘With the Tate, the branding is almost at a subliminal, but powerful level,’ says Grover. ‘You couldn’t have a shopping mall at the Tate, but you must have a shop that draws visitors into it.’

In Herzog de Meuron’s new Tate Modern shop, Grover is designing the furniture. In the current shop, by Lumsden Design Partnership, he has created a photographic frieze over the book with Mike Parsons, and decided to turn the gondola units vertical, not horizontal. ‘That alone had a dramatic effect on sales,’ he says. ‘A shop shouldn’t be library-like.’ ‘It has to be in-keeping,’ adds Grover. ‘It should evoke the spirit of the place, which is why it is increasingly becoming the front window of the gallery.’

With limited edition designs, gallery merchandise can become collectable in its own right. Many museum shops now create specific merchandise around exhibitions: T-shirts, bags, portfolios and graphics. A spokeswoman for the V&A Enterprises, which runs the V&A shops, says it is launching a lot of new merchandise at the opening of Jiricna’s new shop.

‘We try to reflect the creativity of the collections,’ she says. ‘To this end, we work closely with the curators. The products need to be sympathetic.’ Therefore, visitors will find bespoke merchandise for the exhibition they have just enjoyed: for instance, there is currently Christopher Dresser-inspired work in the V&A shop.

This is also the remit at the Design Museum, where it is critical that the products are integrated into the museum experience. ‘Everything we have in the shop has to exemplify our brief of excellence in design,’ says Noah Crutchfield, head of retail at the Design Museum. ‘Therefore we stock classics – Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen, and Vitra miniature chairs – and we also have products related to the exhibitions: for instance, at the moment we have Marc Newson products to coincide with the show. But we wouldn’t have a mug with Newson’s name on it. We try not to slap our logo on everything, and we aim to be a design shop rather than a souvenir shop. We used to sell things like baseball caps, but not any more,’ Crutchfield says.

The shop was designed by Graphic Thought Facility, and one of the bigger sellers is GTF’s Design Museum notebook. ‘It’s the kind of product we want to continue doing,’ says Crutchfield, who adds that the museum’s website, by Design Junction, has become an important extension of the shop, selling five times more than the actual shop. It’s thematically divided – Eating, Living, Playing, Working – and stocks essentials such as a Saul Bass poster, Sam Buxton’s Mikroman (the biggest selling product this year), and brushes from the Imaginary Factory, an initiative from German designers Oliver Vogt and Hermann Weizenegger, commissioned from a workshop in Berlin staffed by the blind (Profile, DW 8 January 2004).

But perhaps the most important aspect of the Design Museum shop is that it contributes more than 10 per cent of the operational budget to the museum – and here lies the essential reason why gallery shops have become so important: not only do they provide vitals funds, they may even help the institution to survive.

-

Post a comment