Enamoured

Hugh Pearman relives the legacy of Charles and Ray Eames through the book An Eames Primer by Charles’ grandson Eames Demetrios

I don’t think anybody has yet done a hatchet job on Charles and Ray Eames, the patron saints of post-war design. They appear to be untouchable. And the Thames & Hudson book An Eames Primer, written by Charles’ grandson (via his little-discussed first marriage) and current director of the Eames office, is hardly likely to stir things up. Yet this is an honest and highly literate book. One you can read with pleasure right through.

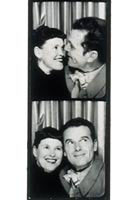

I always winced slightly at the lovey-dovey image the pair presented of themselves in their carefully posed photographs. Tall, handsome, all-American Charles and that funny dumpy little Ray Kaiser with the dazzling smile – the artist student that the older architecture teacher picked up at college when his marriage was on the rocks. Their true relationship – childless as it was – remains somewhat mysterious. The Eameses were intensely private.

And then the work: timeless, brilliant, but not without its flaws. For me, that famous 1956 plywood-shell lounge chair of theirs has always been a hideous, mannered object, and that is from their good period: the late furniture bears no comparison to the early and mid period stuff. And why did they fail in their quest, begun shortly after they met in the early 1940s, and pursued for years, for the single-piece plywood chair? Why did they let Arne Jacobsen beat them to it? Because Charles had decided that it could not be done. But it could.

As the book makes clear, Charles was the ultimate ‘bloke with a shed’. Forever tinkering. Cussedly having to work everything out for himself from first principles, only rarely seeking outside advice on processes (such as glass fibre moulding) he did not at first understand. Burning out hundreds of staff down the years by demanding total loyalty and crazy hours in return (usually) for no credit. Sometimes – as with Harry Bertoia in the early days – they left acrimoniously. Later, they just accepted that this was the Eames way.

The book at least clarifies one myth: the myth of the equal partnership. Yes, Ray was always there. Without her, his work would have turned out very differently. He always gave her credit. It is virtually impossible to determine who did what: they were a unit. But in all the memories of Eameses people faithfully recounted in this book, it was Charles who autocratically ran the office, and made the decisions. Afte

r he had worked himself to death, Ray couldn’t hold it together, despite her relative youth. Could Charles have managed without Ray, finally? Probably. But Ray definitely made him.

But in the end – does it matter? There are all the good chairs. There is that amazing Case Study house. There are the dozens of extraordinary short films and some cracking exhibitions still existent. These things are beyond style and fashion. ‘Innovate as a last resort’, Charles often said. Sweat and determination made their work. An apparent flash of genius would be the result of 30 years’ thinking and design evolution. Along the way, they invented the modern idea of multidiscipline working. So no, there is no point doing a hatchet-job on the Eameses. This book artlessly shows some chinks in the armour. But the armour is burnished bright.

An Eames Primer by Eames Demetrios is published by Thames & Hudson on 25 February, priced £15.95. Eames Demetrios will be giving a talk on 15 February from 12.30-2.30pm at Vitra, 30 Clerkenwell Road, London EC1

-

Post a comment