Young pretenders

Liz Farrelly reviews a book examining the social and economic factors behind the growth of Japan’s youth-obsessed underground subculture.

If you thought that the Japanese version of a geek/ anorak/ trainspotter, known as otaku, is as inoffensive and chuckle-worthy as our own home-grown variety, then the thesis put forward in Little Boy, the Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, will enlighten and shock you.

To say that otaku are demonised, outcast and feared in their native Japan is only one side of the story. That they are also catered to by big business – the media, confectionery giants, toy manufacturers, retail chains – is an undisputed fact, earning many millions of yen for the economy. Meanwhile, they provide both the raw material and an audience for much contemporary cultural output, right across the spectrum, from high- to low-brow art and design (the boundaries blur in Japan). Now otaku have become the subject of academic scrutiny, along with such concepts as kawaii (cute), moe (‘girly’ anime) and yuru chara (kitsch characters), plus the complex dance of cause and effect being played out in relation to the Japanese nation’s search for both a cultural identity and psychological well-being.

The book may be an extensively illustrated and sumptuously printed exhibition catalogue, but unlike the usual coffee-table fodder, Little Boy has a sting in its tail. Published to accompany a blockbuster show held at the Japan Society in New York this summer, featuring contemporary Japanese art and design across various media – plastic figures, book illustration, textile prints, canvases and multimedia assemblage – this book is much more than a visual souvenir.

It features copious reference images from a roster of iconic, nostalgic and highly sought-after characters and toys that are derived from anime and manga, sourced from printed media, television serials, movies and computer games, stretching all the way back to the 1950s. This weighty tome also contains extensive chronologies and highly entertaining essays. Its many knowledgeable contributors contextualise the current crop of cute, quirky, ironic and knowing imagery with historical research into significant landmarks of the post-World War II era, including economic, social, psychological, cultural and aesthetic factors.

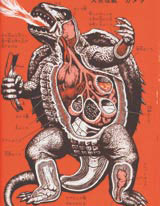

If you need to know who directed the Ultraman series, for which television station, when, and how many episodes it ran to, while enjoying Tohl Narita’s detailed production drawings for said hero’s many, scary adversaries, look no further. Similarly, you’ll find potted histories of Hello Kitty, Godzilla, Akira, Doraemon and more, as well as seminal manga and anime serials. Editor, artist and essayist Takashi Murakami suggests that a clearly delineated, yet heady cocktail of sci-fi, fantasy, cutesy characters and pseudo-porn has created the warped psychological make-up of the otaku, and by way of their influence, the wider community. According to Murakami, the end result is the infantilisation of Japanese society. No one wants to grow up and take responsibility – They’d rather be ‘pure consumers’, creating safe, ‘teenage bedroom’ space, crammed with personal possessions, in which to isolate themselves from the real world.

The traumatic physical and mental shock of the atomic bombs dropped 60 years ago by the American military on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Little Boy was the nickname given to the Hiroshima bomb); the subsequent virtual colonisation of Japan by the US; the treatment of the Japanese economy as an experimental test bed for consumer capitalism; and criticism of this state of affairs being banned from mainstream media, are all held up as causes. That an outlet for the nation’s grief, fear and imagination was found in anime and manga (in print, on TV and in film), ostensibly aimed at children, but consumed by all, and collected and fetishised by otaku, for whom nostalgia is always current, is the result. So too are some stunning pieces of art and design by Murakami, Hideaki Kawashima, Yoshitomo Nara and Oshima Yuki, among others.

Little Boy, the Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, edited by Takashi Murakami, Japan Society and Yale University Press, 2005, priced £35. The complete version of the original 1954 Godzilla (Gojira) movie – with restored anti-nuclear footage that was cut from the US release 50 years ago – is released in the UK on 14 October

All images © Japan Society

-

Post a comment