Educational platform Eyeyah is using design to help kids spot fake news

The creative education platform uses bright illustrations and pop culture references to teach kids digital literacy.

“We don’t know what jobs kids are going to have in 10 years’ time, so our work is about finding ways we can help them along their journey,” says Steve Lawler.

Lawler is the co-founder of Eyeyah, an education platform that uses creativity to engage young people with vital lessons for the digital age. A graphic designer by trade, he tells Design Week that design is a key tool in exploring these topics.

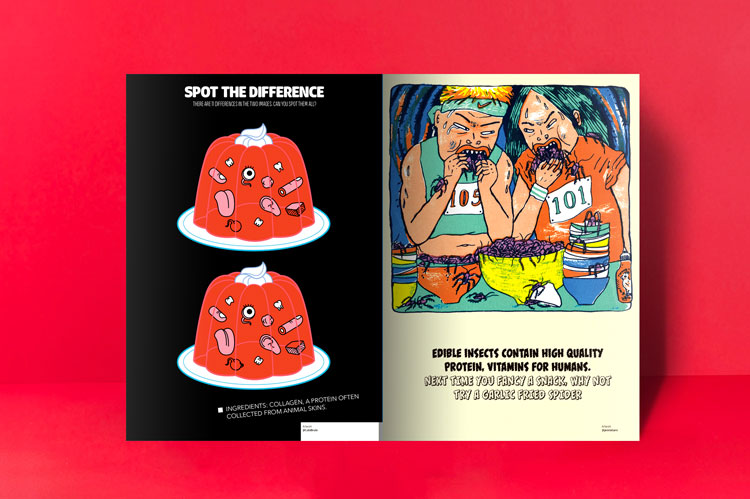

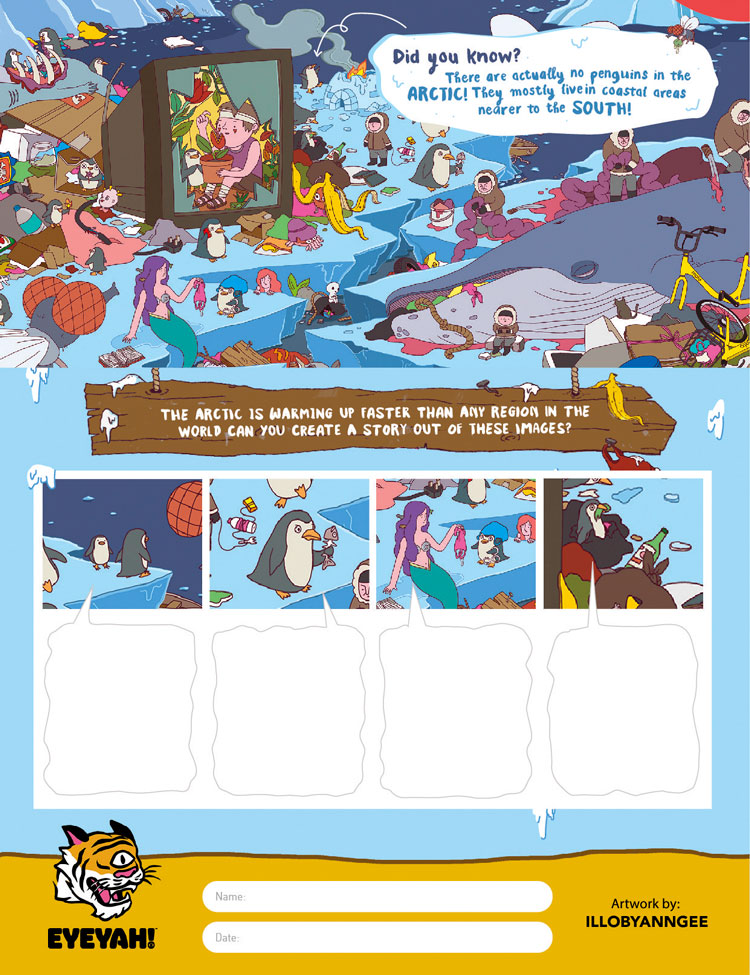

Eyeyah’s offering is three-fold: for each topic focused on, the team aims to put out a magazine-style print publication, social media-based activities and a toolkit for teachers to use in the classroom. The creative platform is approaching its third birthday, and has so far had editions covering trash, food, the internet and oceans. Its latest project has covered the world of fake news.

“Get them thinking critically”

Fake news has been a growing feature of online life for several years. As Eyeyah’s latest publication shows, instances of fake news can range from the fairly innocuous, like dolphins arriving en masse to Venice’s canals during the coronavirus pandemic, to more conspiratorial, like the government using pigeons to spy on the public.

Whatever the example, being able to spot fake news is imperative for a generation of digital natives, Lawler and fellow Eyeyah co-founder Tanya Wilson say, but the information needs to be engaging for it to stick.

“You see a lot of imagery on social media which doesn’t end up having a lot of base,” says Lawler. “And often if it does have an underlying meaning, that meaning is sales-based.” The object of Eyeyah is obviously not to sell young people a product, but rather “get them thinking critically”, he continues.

“We invented fake news headlines of our own”

The fake news publication from Eyeyah – which is digital-only at the moment because of the pandemic – uses a comic book-like illustration style to challenge its young readers. A collection of headlines is presented, some of which are genuine stories, others genuine fakes. The challenge is for young people to distinguish between them.

“We knew we shouldn’t go for anything political given we were aiming this at children, so we tried inventing some fake news headlines of our own” says Wilson.

The process of inventing fake news was an illuminating one, she continues – oftentimes Wilson and Lawler would make something up, only to Google it and find grains of truth in their concoction. The experience highlighted to the pair how easy it is to twist the truth and they say the hope is that young people end up being critical of all news, whether it sounds believable or not.

“Kids aren’t impressed by type and kerning the way we are”

As for the design of the publication itself, Lawler says the intent was not to be “precious” about how it looked. A departure from the previous magazine format, when the fake news publication does go to print, it will take the form of a newspaper.

“It is designed, but we’re blurring the lines to lower the barriers for entry,” he says. “You don’t have to be a design head to enjoy it and learn from it, because kids aren’t necessarily design-heads and aren’t impressed by type and kerning the way we are.”

Previous publications from Wilson and Lawler have invited several different graphic designers to contribute at one time to bring together different visual styles. Again, the fake news edition has departed from tradition and instead has been designed entirely in one style. The result is a set of illustrations that feel as if they’re in the same family, Lawler says.

“We don’t want to appear like finger-wagging parents”

The colourful three-fold magazine-digital-teacher-toolkit approach has worked for Wilson and Lawler for some time now, but the pair have also experimented with other outputs.

“We’ve done black and white zines, exhibitions, augmented reality, virtual reality, pop ups and apps – we’ve experimented with all sorts,” Lawler says, while Wilson adds their work has always been focused on “finding a connection” with Eyeyah’s audience.

The challenge, Lawler says, is always in trying to make the lessons feel credible and worth engaging with. The teacher toolkits have been designed to encourage kids to deconstruct what’s in front of them with minimal adult intervention. Meanwhile, the publication and social content is designed to be relatable beyond a classroom setting.

“We don’t want to appear like finger-wagging, uncool parents,” says Lawler, adding that the fake news publication uses pop culture references, memes and games to entertain as well as teach.

“We can be flexible over different platforms”

Beyond the newspaper itself, the fake news content will also be used in interactive exercises on Eyeyah’s social media and even during the breaks on kids’ television channel Nickelodeon.

“What we’ve found is that actually because of the content we’re covering, we can actually be flexible over different platforms,” Wilson says.

At all times, the intention is to be visually striking. Lawler says this is vital, because “images are the language of young people”. Additionally, an output that is heavily image-based makes it easier for Eyeyah to cross language barriers.

“You don’t have to speak English well to understand a lot of our output, because the imagery does a lot of the work,” he says. “This is a global issue for us, and skills like critical thinking, visual literacy and creativity are key no matter where you are.”

-

Post a comment