Blast from the past

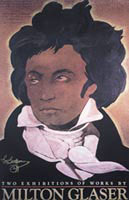

Art is Work showcases work by graphics star Milton Glaser. But his work looks the same as it did 25 years ago, says designer Michael Johnson.

If you were at college with me in the early 1980s you may have wondered why two important graphic design books were conspicuously absent from the library – Pioneers of Modern Typography by Herbert Spencer and Milton Glaser Graphic Design by Milton Glaser.

Well, they weren’t missing exactly – they would come back for a brief spell of about 20 minutes, then I took them out again for another term. You see, these two books formed the backbone of my design education.

One book revealed that graphic design basically consisted of owning a few turn-of-the-century poster books, being able to daub with gouache, dabble in watercolours, embrace stencil type in all its myriad guises and be a dab hand at centring Goudy typeface. The other was full of angry wood type in black, white and red, defiantly rejected illustration of all forms and laid important paving stones for acceptance of photography within design.

I left college with a bizarre portfolio. Most of my layouts seemed to consist of badly drawn flat colour illustrations, crudely bumping into chunky type, often at rakish European angles. Confused? I was.

I may have been muddled, but I loved Glaser’s first book. I loved the psychedelic drawings, the colours. I loved Big Nudes. I even forgave the type (but knew even then that it was a bit dodgy). By then my portfolio and me were muddling away in real design and the more I learnt, the more embarrassed I became of my (by now secret) admiration of a man whose work had become so conspicuously untrendy. As I realised that European modernism was the cornerstone of just about everything admired, I also realised that Pioneers of Modern Typography wasn’t so clunky after all.

If my US sources are to be believed, Glaser and fellow “old school” stablemate Massimo Vignelli have not taken kindly to the fall-from-grace illustrated by my changed mindset. Presumably they enjoyed being the epitome of the American design dream – the have-stencil-will-stencil, go-Bodoni-go design mentality that pervades most US design annuals of the 1970s and 1980s. It’s hardly surprising that US design embraced David Carson’s blitzkrieg typographic assault of the early 1990s with such open arms, because everything else had become so dull.

While Vignelli has been the most outspoken about the new design, his work, probably due to its ruthless reduction to five typefaces and three colours, at least stands up in today’s pseudo-modernist environment. Glaser’s, on the other hand, seems time-locked. A world where every space on layouts is filled, decorative borders are mandatory and most colours flat and pastel.

I had hoped Art is Work – his new book, made 25 years after his first – would shed some light on what my old mentor had been up to. I wouldn’t even have minded if he had merely added a couple of chapters at the end of the old book.

Art is Work thumped down on to my desk, an imposing 300-page volume with a confusing title, offering up “a glorious celebration of one of the most extraordinarily versatile and acclaimed graphic artists of our time”, according to the flaps. Now for the awful truth – you haven’t seen much of his latest work because it looks pretty similar to the work he did 25 years ago. Instead, we get pages of homages to Monet, pseudo-erotic illustrations and interminable case studies of restaurant designs which all look pretty much like the set of the film Bugsy Malone, all Art Deco references with a few post-modern squiggles thrown in.

We get detailed drawings of typeface designs, most of which feature those funny cross bars and stencilly bits you used to see at the local wine bar when they “got the designers in”. “The diagonal cross bar seemed interesting enough to build a complete alphabet around it,” explains Glaser. Not interesting enough, I fear.

There are pages from sketchbooks of Italian holidays, designs for Alessi chopping boards with cows’ feet (a joke, I hope), a revival of the Grand Union case study from the first book and some Catalonian newspaper designs. Had Glaser designed a kitchen sink in the past 25 years, I think we would have got that, too.

This is all presented with big pictures and captions written by Glaser. There is an attempt at analysis to make a clear break between chapters by making use of the interview techniques used in Alan Fletcher’s Beware Wet Paint, but essentially this is a book about Glaser, by Glaser.

While the Fletcher book was a genuine insight into that man’s work post-Pentagram, and is obviously aided by Jeremy Myerson and publisher Phaidon’s views, Glaser’s is in need of an outside influence, someone to shave off some of the dodgy projects and bring the pagination down to a useful length. Of course, that’s easier said than done. Thames & Hudson presumably thought this was a good idea for a book (and it was), but sending an editor into battle with all guns blazing with one of the giants of graphic design is a fairly onerous task.

However, it isn’t all a disappointment. The section on posters makes interesting reading and you can only marvel at how many times Glaser has managed to sell the idea of a strangely trimmed poster to clients. In fact, one recent poster for a series of design lectures which until now only managed to stun by its mediocrity, now makes complete sense as you realise that it was photographed and trimmed to look as if it was wrapped around a column. I just presumed that it was a dodgy tranny.

Some of the most interesting insights come as Glaser discusses some of the classics featured in the first book, such as his now much parodied, but much-loved Bob Dylan poster where the singer’s hair becomes psychedelic squiggles, and, of course, the I k NY symbol. He discusses the Dylan poster as done at a time “which has clearly passed”. He suggests that to call I k NY “the most frequently replicated piece of ephemera of the century” is hyperbole, but we are left with the feeling that this is hype he is happy with. This is prior to his bemoaning the lack of adequate copyright protection on the logo (basically, he has been monumentally ripped off for 25 years and there’s nothing he can do about it). But the example of the I k NGORONGORO bumper sticker is a classic and Glaser has the good grace to both recognise this, and print it.

There is a long section on illustrations and sketching, but will it really be of that much use to illustrators? I’m not sure – they can do exactly what Glaser himself freely admits he did – go back to first principles, study fine art and borrow as much as you feel you can get away with.

Whether Glaser’s views and work will be of influence a second time around as illustration finally drags itself out of the doldrums remains to be seen. The current revival of curvy-linear drawing and flat colours owes more to Brit Art, Aubrey Beardsley and those laminated aeroplane information sheets stashed next to the sick bags in the back of the seat in front.

But if you follow the Glaser dictum, design is, by definition, drawing, which must be mastered if you are going to become a true master craftsman and compare yourself to Michaelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci (as he happily does). Which is odd, as designer training is now about grappling with the requirements of design in the computer age, not stretching watercolour paper. It comes as no surprise that the latest generation of illustrators draws directly on the computer, but we are left in no doubt as to Glaser’s views about the negative influences of the computer – you know, “only a tool”, “invention of the devil”, the usual stuff. As for Leonardo, I think if he were alive today he would have his head in a manual learning 3D drawing programs with the best of them.

As for the historical references that pepper the book, the sabbaticals in Bologna, the homages to Piero della Francesca. You can’t help feeling that this and his own references to past glories, reveal one of the truths of this book – here is a man who has designed the same way for 40-odd years and his early successes are inevitably going to time-lock his style. Graphic innovators often find themselves inexorably linked to the period that made their name – for John Gorham think 1970s, for Neville Brody, 1980s, for Carson, 1990s. As a rule of thumb, designers learn in their 20s, make their name in their 30s, and consolidate in their 40s. After that, well, it’s very much up to either their willingness to stay interested or their ability to change their spots. And while he’d hate to admit it, Glaser’s way of working is a recognisable style, not a method. A style that you will either love or hate.

The most telling item, buried deep in a section of transcribed talks is a top-ten list of “designer don’ts” entitled The Road to Hell. It includes ethical no-goes such as “designing a children’s cereal pack with a high sugar content” at number six, and “designing a promotion for a diet product that you know doesn’t work”, at number eight. Unfortunately, it stops short of number 11, which should be “Don’t produce a book of your work 25 years after your first without a good editor’s advice”. n

Art is Work by Milton Glaser, is published by Thames & Hudson at the end of November, priced £48

-

Post a comment