Being disruptive – how design can challenge, entertain and delight

As a brief, ‘disruptive’ is a deliciously open one.

The notion was set out back in May as the theme for this year’s Design Museum Designers in Residence show, and has seen the four selected designers take over the establishment to explore and challenge the creative possibilities of a word that usually has less-than positive connotations.

It’s perhaps little surprise that such an open idea has produced four such different projects from the four designers – James Christian, Ilona Gaynor, Torsten Sherwood and Patrick Stevenson-Keating.

As these creatives have proved, disruption is a word loaded with possibilities – be it as a force for social good, a basis for play, an inspiration for a new economic system or a catalyst to reimagine the courtroom system.

And while each project is wildly different from the next, they’re united in the sense of using disruption in its innovative, positive sense, rather than its destructive one.

However, Gaynor tells us that it was the sense of rebellion the brief connotes that inspired her first idea for the project.

‘It started out looking at protests, and interesting ways to protest legally, as it’s actually illegal to protest around the Houses of Parliament,’ she explains.

The idea was shelved when she saw the V&A’s plans for its Disobedient Objects show, as well as the realisation that the four-month deadline for the project was far too short for the depth of research she would need.

Instead, the Royal College of Art graduate set about designing a court of law resembling a television studio, bringing the idea of ‘legal theatre’ to its logical conclusion.

Through 3D dioramas, photographs, graphics, models and text, she narrates a hypothetical legal case of televised National Lottery draw fixing.

‘It’s design as entertainment’, says Gaynor. ‘There are very interesting incidents [in law] that can occur because of incredibly banal structures, and what I’m trying to do is to create some sort of vaguely entertaining moments within those structures of how they work’.

Her imagined courtroom builds on the idea of using video in trials, where the jury sometimes views proceedings via cameras – not unlike how we watch television.

‘We are all familiar with the language of cinema and television’, says Gaynor. ‘My interest lies in the idea of looking at the court as a special arrangement, and how that changes perspectives, and how we begin to investigate, legally, what on earth happened at a singular event’.

Another designer disrupting inherited, and for the most part unchallenged, ideas, is Patrick Stevenson-Keating, who has used his space in the gallery to set up a series of pieces that propose alternative ideas for financial objects like cash machines and payment devices.

The absurdity of the appearance for some pieces is brilliant: Stevenson-Keating playfully challenges the idea of a payment device with a balloon that inflates to demonstrate available funds, deflates as a payment is made, then settles on a size that represents the post-payment balance.

Stevenson-Keating, founder of design studio, Studio PSK, says that idea worked on the basis of disruption as deviating from accepted norms, and led to an exploration of ‘what economics actually was’.

Objects like cash machines, coins and banknotes (all of which are themselves, designed objects) have become so accepted that we barely acknowledge them; and so his designs aimed not to provide answers or proposals for changing these systems, but to instigate conversations about alternatives.

‘There’s something very nice about creating physical objects similar to those that people interact with on a daily basis but which are very obviously – because of heir aesthetics – different’, he says.

‘They will probably be quite abstract but familiar enough so that people can still understand what they are’.

Source: Cat Garcia

James Christian

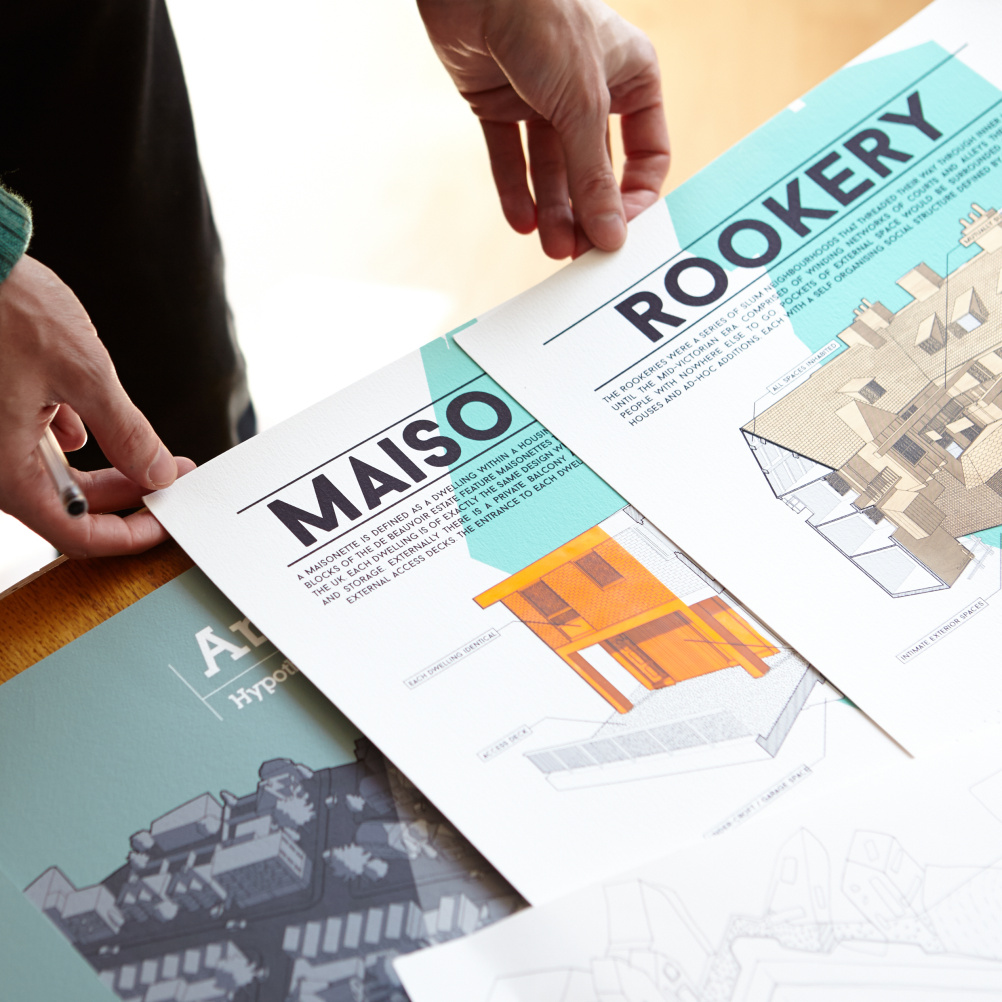

Having examined law and finance, the show next moves on to housing, thanks to James Christian’s designs, which draw on historic housing concepts to image a new kind for the future, modelled to sit within east London’s De Beauvoir Estate.

Source: Cat Garcia

James Christian’s designs

Through some lovely graphics and a series of models (peopled with charming characters like the haughty-looking, dungarees sporting lady shown below), Christian’s project draws on historic housing with London-connotations: the 18th and 19th century slums of the rookeries, and London Bridge in the 17th century.

Through examining where these models failed and where they succeeded, Christian developed ideas for new housing appropriate for the De Beauvoir Estate.

Source: Cat Garcia

James Christian’s designs

‘The idea of looking at social housing expanded and expanded as I found out more about it’, he tells us.

The project has been described by the designer as ‘pragmatic fantasy’, and he says that the disruptive element stems from ‘looking for design in the wrong places – I think that’s innately disruptive’.

Torsten Sherwood’s project differs to those of his fellow residents in its inherent marketability. Where the others create miniature, reimagined spaces, his is a piece of pure, yet imaginative product design, creating a construction system for children using cardboard discs.

‘My starting point was not directly the notion of disruption’, he tells us. ‘I had the idea, but the [disruption] is directed by the thought “what if Lego wasn’t a brick”. I wanted to challenge that’.

The discs Sherwood designed deviate from normal construction toys in the fact that rather than tessellating, they overlap, creating almost endless possibilities for children to build shapes, patterns and little cardboard cities.

As well as displaying what can be created with the discs, the show also invites visitors to play with the pieces themselves.

Sherwood says, ‘I hope it introduces some more substantial themes for [visitors] to think about in a new way: play, instinct, behaviour, architecture and construction.’

The material is inherent in the success of the project. As one of Sherwood’s graphics reminds us, a common, almost clichéd complaint is that of a child being more interested in a toy’s box than the toy itself.

The graphic reads, ‘Because the box is “worthless”, the child feels able to play with it, alter it and decorate it without fear of reproach.

‘The worthless cardboard box becomes something precious in the child’s eyes, and in doing so challenges what we might perceive as valuable.’

It’s this challenging of perceptions that unites the designers in residence, and their approaches make us also challenge inherited notions – whether it’s of housing, law, play, finance or design itself. And if that’s not disruptive, we’re not sure what is.

Source: Cat Garcia

From Ilona Gaynor’s piece

Designers in Residence is on show at the Design Museum, 28 Shad Thames, London SE1 2YD from 10 September – 8 March

-

Post a comment