Science Gallery exhibition asks: to what extent should we alter our bodies?

Spare Parts features a range of installations and exhibits that look at how we approach body part regeneration and organ transplantation, alongside the ethical issues around the subject.

A new exhibition at the Science Gallery London, is exploring the idea of human repair and regeneration, with a series of installations that aim to spark debate.

The show, called Spare Parts, raises a wide range of questions, such as what human repair really means, whether “spare parts” can exist outside of the human body and whether a body could be made up of a range of regenerated parts.

It also looks at the impact on people living with replacement organs or limbs, considers various ethical questions surrounding synthetic regeneration and explores the science and technology involved in the repair and alteration of human bodies.

The show has been developed alongside scientists from King’s College London and draws on some of the research they have been involved in.

Curator Stephanie Delcroix says that rather than pushing a message, the show is inviting visitors to ask questions.

“It is for the audience to try and think about what biological repair of the body might involve and whether we can be more creative with the way we approach human repair and the impact on human lives,” she says. “The aim of the exhibition is to spark healthy debate about the motivations and implications of the research and practice in relation to human repair.”

Exhibitors responded to an open call for entries, which welcomed both new and existing projects, exploring topics including organ transplantation, regeneration, stem cell research and prosthetics, as well as the ethical, emotional and economic considerations about all of these.

“Some of the artists and collaborators in this exhibition are essentially looking at what the human body is, how it relates to our identity, but also what motivates us in the search for a surrogate body or replacement part,” Delcroix says.

Examples of work include 3D-printed models of hearts, body parts crafted from textiles and audio-visual installations discussing the impact of organ transplantation, and many other installations.

In the courtyard outside the gallery stands a piece by artists and curators Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr known as Vessels of Care and Control: Compostcubator 2.

The installation consists of an incubator, which “uses the power of microbes that eat compost to generate heat,” Delcroix says. The heat, in turn, warms up water, which travels through a pipe to a bioreactor, which contains a petri dish with cells growing inside it.

“They are looking at how we create and maintain forms of life,” Delcroix adds. “They are interested in combining both low-fi and technological approaches to scientific practice.”

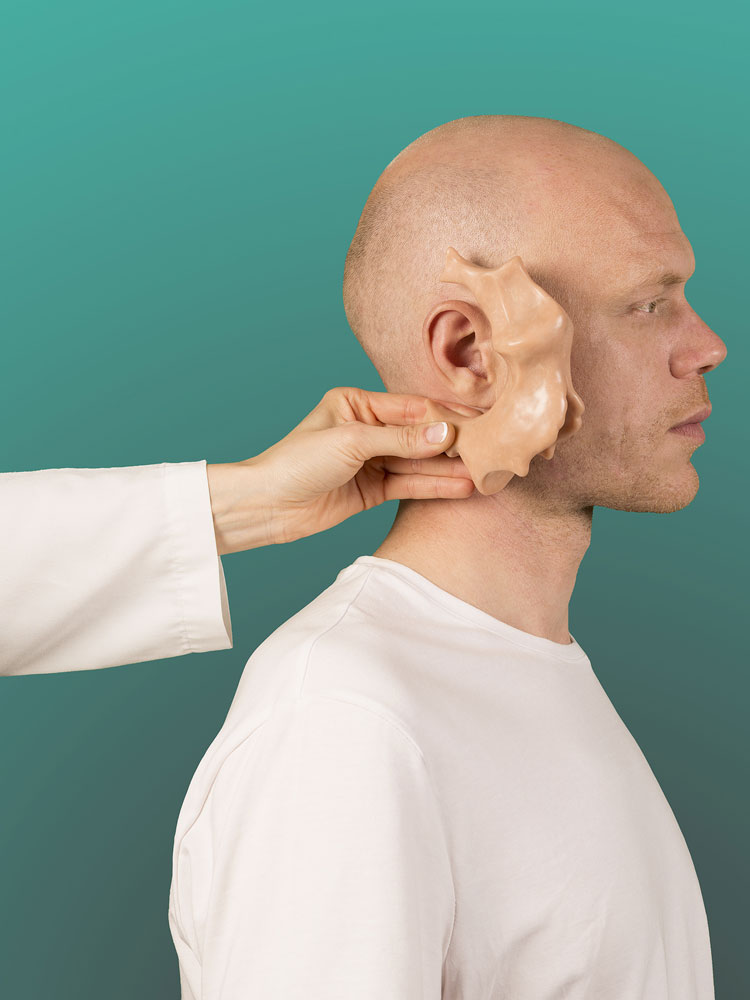

Another highlight is The Self-Donor Workshop by designer Tina Gorjanc. Delcroix explains that while humans are “very far away” from being able to engineer organs, there is existing research around the creation of “organoids”, tissue cultures that could play a role in organ repair.

This research inspired Gorjnac’s installation, Delcroix says, which is based on a speculative scenario featuring a boutique-workshop that people could visit to donate cells that could then be used to make organs.

The idea is that these could then be used to replace the donor’s own failing organs, eliminating the need for external donors.

The installation raises further questions, Delcroix adds, such as whether the aesthetic appearance of an organ is important and whether bioengineers should be “designing” organs to be the right shape.

Another interesting piece by artist and designer Svenja Kratz, is known as the Monument to Immortality, which plays with the idea of “downloading” human consciousness onto a machine and continuing to survive as a disembodied entity.

The installation consists of a holographic display of moving cells, 3D-printed sculptures based on the movement of cells, and an element known as the Ghost Writer, which will write a text created by Kratz in a “handwritten script”. The piece explores the idea of separating the mind from the body and the capabilities of continuing life through artificial intelligence (AI) tech.

There are many interactive elements throughout the show, including a piece called Life Pulse by artist Michael Pinsky, which people see as they enter. The piece is made up of four columns, which register a visitor’s heartbeat when they touch it, and light up to match its rhythm.

A section at the centre of the exhibition, known as The Gut, includes hands-on activities where visitors can “splice cacti” as part of a display looking into tissue grafting and try their hand at stitching together electrodes in a display centred around biotechnology.

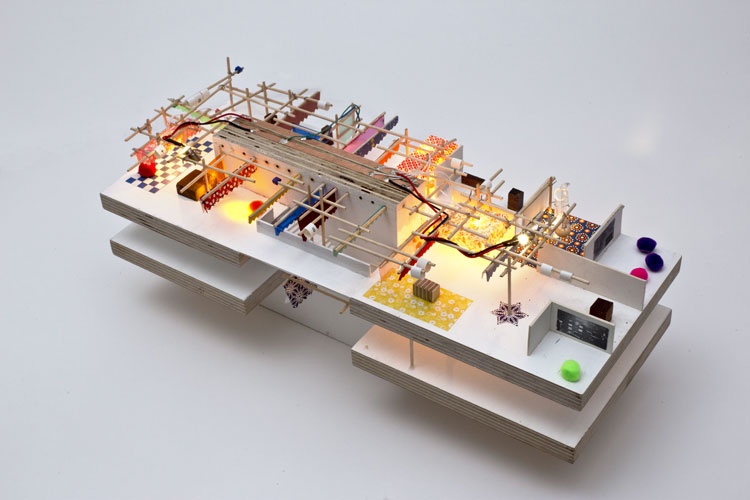

The space has been designed as an “immersive experience” by Jan Kattein Architects.

The architectural practice’s founder, Jan Kattein, describes the design as “a journey through a series of wondrous laboratories that invite for engagement, participation or contemplation.”

The three-dimensional design consists of a gridded wooden framework, which has been fitted onto walls, floors and the ceiling, aiming to create a “multi-dimensional and multi-sensual landscape”.

“The inter-connected frames variously act as enclosure, plinth, screen, frame or support for the exhibits,” Kattein says.

Geometrically patterned curtains hang on hooks attached to the wooden frames between some of the exhibits, while others hold lamps or canopies.

“The theme of bodily transfiguration translates into the spatial transfiguration of the gallery space itself,” Kattein adds.

A wide colour palette has been used in the design, to “complement the largely monochrome artworks” and “contrast the serious and sometimes controversial subject matter of the exhibition,” he says.

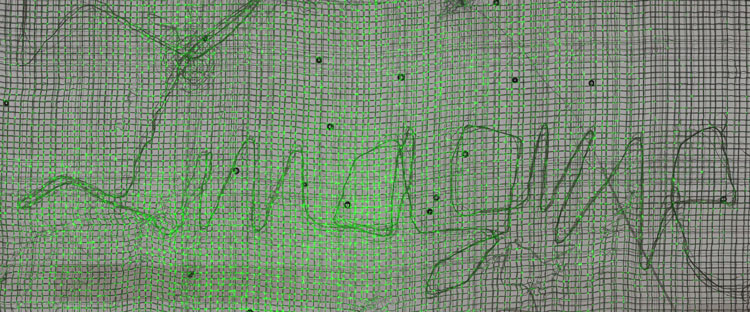

The wayfinding graphics and signage for the exhibition have been designed by Marcia Mihotich, who has created a series of flat icon graphics such as an eye, a heart and a piece of machinery, which she says aim to encapsulate different exhibits in the space.

She adds that the suite of graphic icons was originally inspired by the idea of model kits which come with a range of pieces that can be put together to create something.

The icons will appear together on a welcome board at the start of the exhibition and on information relating to each exhibit.

A series of events will accompany the exhibition.

Spare Parts: Rethinking Human Repair, runs from 28 February – 12 May 2019 at the Science Gallery London, Great Maze Pond, London, SE1 9GU. For more information, head here.

-

Post a comment