The domination game

As the giant corporations expand and dominate the world markets the homogenisation of global brands diminishes all forms of cultural diversity

So far this year we’ve seen Unilever acquire Ben and Jerry’s and Best Foods, Interbrew has bought Bass and Whitbread, France Telecom has bought Orange, and in our industry WPP has bought Young & Rubicam (which has in turn bought The Partners). Have businesses traditionally associated with brand building become preoccupied with empire-building? The “paint the map red” mentality of yesteryear governments has simply worked its way into corporate life.

It really is a sobering thought that many multinationals today have a far greater wealth than some of the countries in which they trade, and that some chief executives effectively have more international power than elected presidents. So what?Ã you may say and you’d be right. There is nothing wrong or immoral with the free market economy. A large number of UK design businesses have flourished on the back of the global branding projects which have emerged in the wake of acquisition or extended distribution, so who am I to complain?

But, I am faced with a marketing quandary. Isn’t the way in which the corporate world is moving (bigger, fewer) diametrically opposed to the way in which we are led to believe today’s global consumer is moving? On the one hand, we extol the virtues of global brands: standardised, quality assured, a simpler choice. Then we talk of consumers as discerning, experimental, sensation seeking and confident in their own ability to choose. They are marketing cynical, fascinated by esoteric brands and have shortening attention spans. Customisation is the current new consumer thang, for God’s sake! As a punter I’m starting to feel manipulated and tired by a great number of global brands. The world I see is becoming a little bit duller.

Of course I’m reassured to see a Visa sign in Bangkok, glad to know I can pick up a tube of Colgate in Buenos Aires, and guaranteed to turn on to MTV anywhere I’m staying. Global brands certainly aren’t bad. But I doubt I’m alone in saying that the level of affection for my local Pizza Express is considerably higher than for Pizza Hut (London, Florida, or Jakarta outlets). I coveted Sony for years, but I’d sooner have a Naim today. And I genuinely chose not to buy Saab again when I learned it shared a GM Cavalier chassis. Even global brand greats that I’ve bought for years, like Mars and Coca-Cola, have effectively been relegated to being a low commitmentà or passiveà purchase. Some might argue that it’s a sign of greatness, but it does seem to fly in the face of the concept of relationship marketing.

More often than not, global brands succeed because they exist, not because they necessarily inspire a strong emotional response. As a design consultant I find global projects equally fatiguing. Big? Yes. Politically sensitive? Certainly. Complicated to implement? You bet! But creatively challenging or satisfying? For every clever FedEx marque there are a hundred no-brainers. The inevitable lowest common denominator logo in lieu of an idea emerges.

Then there’s the messy business of local brands trying to form a template that accommodates local looks and prejudices. If we’re honest they’re usually an exercise in compromise and blowing huge multinational budgets. Empire-building means that the calls to create something new steadily become fewer and further between. Acquisition and rationalisation have replaced innovation, and success is purely measured in terms of size. Quirky or niche local offers, regardless of their ability to endure, are rapidly becoming things of the past.

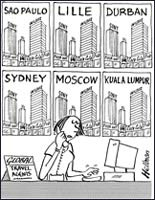

While I can offer no magic solutions to the immediate effects of global domination, I do retain faith in human nature. After all, the same executive who travels to Brazil to discuss identity harmonisation will fly back to his wife to bemoan the fact that the streets of Sao Paulo mirror Croydon, with a McDonalds and an HSBC on every corner. The marketing director charged with extending distribution in Northern Europe will have decided to boycott BMW when his car is up for renewal because of the Rover debacle. His colleague in sales will consider it a travesty that his British pint is now technically Belgian.

And, sadly, their managing director, who has focused on culling his brand portfolio for the past two years, will speak out at a conference about the lack of innovation in marketing. Perhaps today’s empire builders should learn from the past: ignore cultural diversity and you cut yourself off from the people. Exclude their needs in your plans and they will utimately overthrow you.

-

Post a comment