Art of Digital Preservation seeks to save cyber heritage

A group of experts is launching a project which aims to prevent historical digital material including digital designs from being wiped out permanently.

The University of Portsmouth is leading the Art of Digital Preservation initiative, which will take place over three symposiums, kicking off in June.

The project will be headed by Dr Janet Delve and Dr David Anderson (pictured) from the University of Portsmouth. Anderson says, ’Interactive digital artworks, 3D visualisations and video games are highly complex digital objects which are not capable of being faithfully preserved over the long term using traditional techniques.’

As hardware becomes obsolete, software is often lost, unable to run on new machines. Where it can be saved, a ’migration’ technique is used which can mean adapting files to make them compatible, although, as Anderson points out, this is ’costly, time-consuming and complicated’.

He says that with ’sophisticated digital objects like computer games, this technique can break down’. Anderson believes ’virtualisation’ techniques abstracting information through a unit which sits between old and new hardware are more effective.

Anderson believes the argument for preservation is made all the more potent by standing ’legal mandates’ for national libraries to preserve digital data. Indeed, the British Library is one of the partners in the Art of Digital Preservation project.

Whatever the conclusions to be drawn from these meetings which will focus on preservation solutions the gatekeepers who choose what is preserved are likely to be the museums and galleries that already make decisions on non-digital cultural preservation, according to Anderson.

Poke co-founder Nicolas Roope, who has worked in the digital industry for 15 years, says, ’There is always a danger that the dominant voices rewrite history to inflate their role and influence.’ He asks, ’What is the most salient and important [material] and who even remembers? It is the hardest question, but also the most interesting.’

Roope started out working with creative group Antirom in the 1990s and says its work ’uncovered some interesting truths about interactivity and would still serve as useful lessons today if all of that work was available to experience. But it’s not.’

Roope says, ’Browser plug-ins are no longer compatible with the original files. Operating systems cannot run the original exe files. And this isn’t just true of our work, it’s true for the work of a generation, one which arguably laid the foundations for what interactive media has become.’

As well as preserving for the sake of cultural recording, Roope argues that understanding where digital designs came from helps us understand where the industry is. ’It also stops us from repeating the same mistakes,’ he says. ’I still see so much work today that makes the same mistakes we saw and responded to 15 years ago, but those insights are buried under15 years of incompatibility, so no one can learn from them.’

There is an argument that, to a degree, the Internet itself is a digital archive, but tangible digital hardware objects will also need to be saved.

Kin co-founder Kevin Palmer says, ’How do you preserve arcade games they can’t always be stored on the Internet, the mother of all archives. Data has to be stored faithfully so it works on the right-size screens.’

Symposium schedule

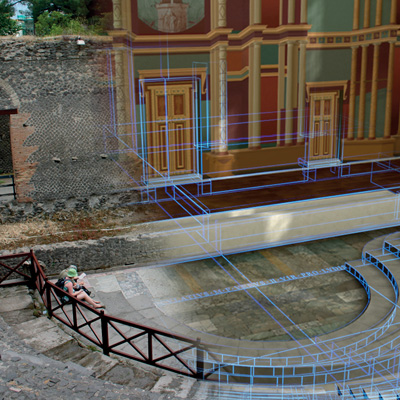

- The first symposium, Simulisations and Visualisations, will be held at King’s College London on 16-17 June

- The University of Glasgow will hold Software Based Art in autumn 2011

- Gaming Environments and Virtual Worlds will take place in Cardiff early in 2012

-

Post a comment