A mass-ive mistake

In an era of consumer empowerment and targeted marketing, David Bernstein is astounded tha big organisations can still treat customers like number

This is a true story. It concerns a civil servant and a milkman. Alas, the two never met…

The former, a spokeswoman for the Department of Work and Pensions, appeared last month on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. You may remember that some 26 000 letters from the DWP went walkabout. A recipient in Derby, for example, found two letters in her envelope, one for her and another for a lady in Barnsley. Now these were not bland notices but payment particulars together with names, addresses and bank details. Duly quizzed about the DWP’s course of action, the spokeswoman replied, ‘We clearly have to treat our customers as individuals.’

Epiphany. Did it really take a major crisis for this senior civil servant to realise that customers are more than numbers? Though, in a world where phone calls to companies often involve the customer in a ‘conversation’ with a robot, is it any wonder the caller is regarded as a dehumanised being?

The novelist JB Priestley coined the term ‘admass’ to describe the audience – grey and amorphous – envisaged by an advertiser. Though he may have done the advertising and marketing industry a disservice, for some it was a useful wake-up call. The sophisticated advertiser realised that if you treat the audience as a mass you inevitably produce grey and amorphous advertising.

I was fortunate to be warned off using the term ‘mass communication’ by an early mentor. ‘Yes, advertising does address a mass audience, but one at a time,’ he said. For the recipient the communication is one-to-one. He or she does not want to be thought of as part of a crowd. Ideally, communication is a dialogue where parade ground bellowing has no place.

The professional writer envisages not admass but a single, sentient person and manages to convey the impression that the message is tailor-made for that person, although this may demand from the latter a willing suspension of disbelief. The writer has to empathise, to play both roles in the dialogue, that of the seller and the would-be purchaser. Only by so doing can the writer structure the argument in the optimum order, pre-empting any putative objection.

If the DWP fiasco and subsequent utterance are any guide, the civil service may be high on tea but low on empathy. Contrast their performance with that of the milkman who was also interviewed on the BBC a couple of weeks later for the TV programme Working Lunch. It transpires that the milkman is making a comeback – the range of goods, and the personal and convenient service he provides, offer a welcome contrast to the largely impersonal supermarket.

The programme introduced us to the Milkman of the Year 2005, who has done the job for 26 years. He was asked, ‘What is the most important part of your job?’ His immediate answer delighted me. ‘Communication,’ he said. Knowing what each customer wants, how much, when and so on. Getting your customers confused – and, in turn confusing them – is clearly anathema, not to say unprofitable.

I hoped that the lady from the DWP was watching. She might also have learned another truth, the need to distinguish between what’s important and what’s urgent. The interviewer put a final question. What piece of advice would he give a novice milkman starting out? ‘Know where there’s a loo. Crucial at three o’clock in the morning,’ was his reply.

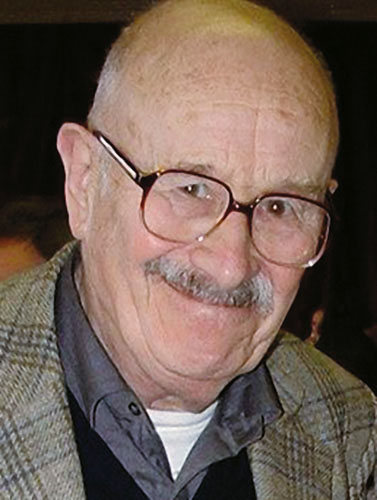

David Bernstein

-

Post a comment