“We wanted to do an exhibition where women designers were at the centre of the narrative”

New York’s Museum of Arts and Design is set to open the Pathmakers exhibition, which looks at the role of women in craft, art and design from the post-war years up to the present day.

Pathfinders showcases the work of 42 artists and designers, from Anni Albers and Eva Ziesel to contemporary practitioners like Hella Jongerius and Front Design.

We speak to exhibition curator Jennifer Scanlan about why the museum felt it needed to focus on the work of female designers and whether or not women are well-represented in design today.

Design Week: Why do you think the role of women in late 20th-century design has been under-examined and why do you think this exhibition is necessary?

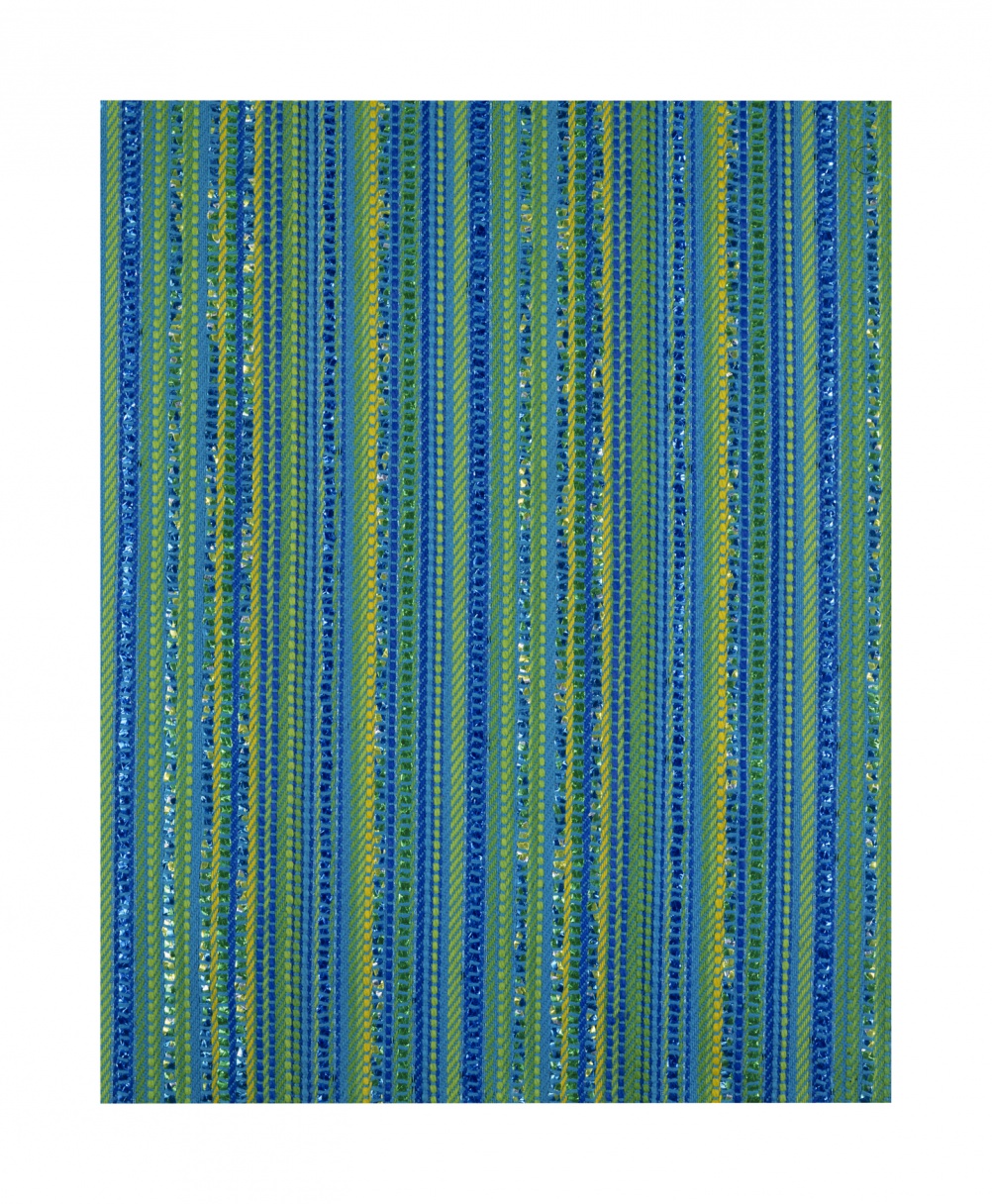

Jennifer Scanlan: Design history tends to focus on areas which were largely dominated by men in the postwar period: furniture, industrial design, architecture. Women often show up on the periphery, because they were usually working in fields treated as supplemental, such as ceramics, textiles, and metal. We wanted to do an exhibition where women were at the centre of the narrative, so we focused on these materials. This allows us to present a broader, more inclusive picture of the time period, and expand ideas about what design can be. I should point out that there has been significant scholarship on women in design history, and much of that has come from the UK. For this exhibition in particular, we owe a great debt to two British scholars, currently living in the US, who organized important exhibitions focusing on women in design: Pat Kirkham, professor at the Bard Graduate Center, and Juliet Kinchin, curator at the Museum of Modern Art.

Photo by Andres Ramirez

DW: How did you decide which designers to focus on for the Pathmakers exhibition, and what (if anything) do you think unites them?

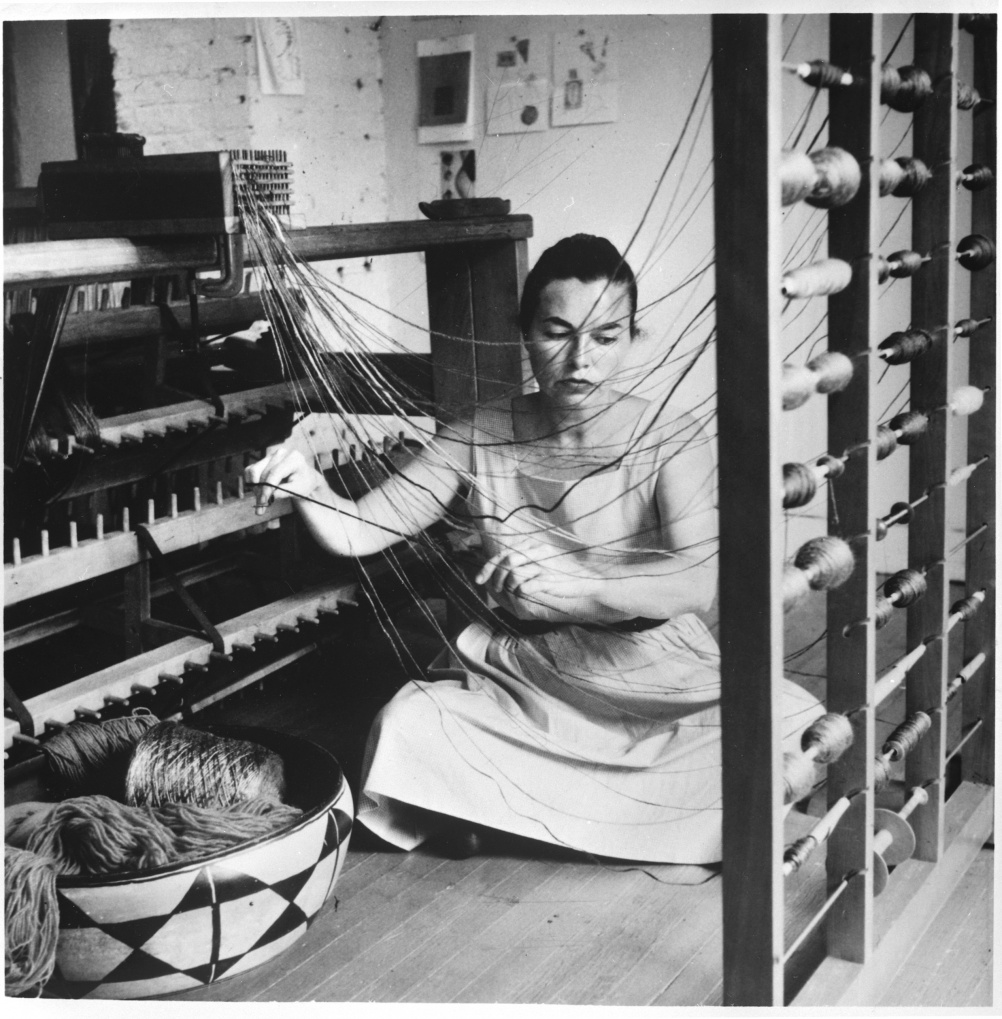

JS: We wanted to show a broad range of women with many different kinds of design practices. So, for example, we included Eva Zeisel, who designed ceramics on an industrial scale, Edith Heath who designed for limited production, and Karen Karnes, who handmade her pieces one at a time. The one thing that unites all the women in the exhibition is engagement with materials and making, which is at the heart of all exhibitions at the Museum of Arts and Design. In the post-war period, an era with rigid gender roles, a focus on craft skills and materials provided many of these women with the opportunity to professionalise, within a context that had the aura of the domestic and feminine. For example, Dorothy Liebes was a textile consultant for the chemical company DuPont, hardly a traditionally feminine role. But ads and promotional materials often showed her handweaving at a loom.

DW: Are there any examples of women or groups of women designers who were particularly influential in the post-war period?

JS: Zeisel and Liebes were very well-known successful designers in the post-war period. Marianne Strengell was important not only as a designer, but as a teacher at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and was connected to many of the most important designers of the era as students or colleagues: Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia, Eero Saarinen. Anni Albers was the subject of the first one-woman textile exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and was hugely influential for her lectures and writing.

DW: Were there geographical areas or disciplines in which women achieved more influence? And if so why do you think this is?

JS: In terms of geographic areas, the exhibition focused on the US and Scandinavia. Scandinavia paralleled the US in a few different conditions: 1) they had not been as hard hit by World War II, so their economies were strong and open to including women 2) they had influential vernacular craft revivals in the late-19th and early-20th centuries that was spearheaded to a large part by women, so women already had leadership roles in this sector 3) their post-war design incorporated these vernacular crafts, expanding opportunities for women in the design fields. In terms of disciplines, as I mentioned, areas such as textiles, ceramics, and metals offered opportunities for women to professionalise as teachers and designers, not always the case in other fields.

DW: From the exhibition, are you able to pick one designer whose work you think has been particularly under-appreciated?

JS: We have some wonderful works by Alice Parrott, a weaver and textile designer based in the Southwest. Her simple hanten shirts were prized by artists, designers, and craftspeople, including Isamu Noguchi, Sam Maloof, and Agnes Martin (whose shirt appears in the exhibition), and her dinner table guests included these and many others. I wish I could have heard some of those conversations!

DW: Do you think the situation for contemporary female designers has changed or do you think they are perceived as women first and designers second?

JS: I think discrimination in the design world is much more subtle than putting women into a special category. For example, I took a look at stories on the Design Week website. In the posts tagged “People” that focus on a single person (I only counted back to the beginning of 2011) you have 79 that focus on a man and 18 that focus on a woman (in case you are thinking there might be more representation of women in the groups or duos featured, there isn’t). Of course, this is by no means unique to you – one of the contemporary designers in Pathmakers, Gabriel Maher, did a similar survey of photographs of designers in FRAME magazine from Nov/Dec 2013 to Nov/Dec 2014 and found exactly the same proportion of males to females. I think the media has a great opportunity, and even responsibility, to contribute to change in this regard. So I’m glad you are dedicating space to this exhibition, definitely a great step!

Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft and Design, Midcentury and Today, is at the Museum of Arts and Design, 2 Columbus Circle, New York, NY 10019, from 28 April-27 September.

-

Post a comment