Animal instinct

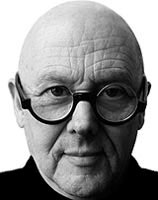

Continuing the Heroes series, Mike Dempsey meets up with the creative alchemist Michael Wolff

He has been accused of being wacky, off-the-wall, eccentric and even impossible. But what is it that has made Michael Wolff shun conventional ways of working?

We met at his home on the edge of London’s Bloomsbury. I sat at his generous kitchen table, admiring the impressive arrangement of flowers placed at its centre, while Wolff busied himself chopping vegetables and preparing rice for the meal we are about to share.

Homes are incredibly revealing and Wolff’s has a relaxed feeling of comfortable clutter. Nothing is overly self-conscious or mannered. It reflects an unpretentiousness that is evident in Wolff’s character. It also mirrors his love of eccentricity. Sitting alongside the flowers is a large irregular shaped rock; in its centre is a small hollow to cradle a night-light. Huddled around this are three tiny carved monkeys warming themselves.

Across the kitchen I notice his cat Lucy, soaking up the warmth of the Aga. She has been his companion for 15 years, and a silent witness to much of Wolff’s more recent roller-coaster life.

He was born in 1933, of Russian parents who had emigrated from St Petersburg. His mother was a vivacious, free-spirited woman and was, Wolff admits, a big influence on him. With her and his father, a salesman, he lived in London’s Belsize Park.

When the war started Wolff, along with a great many children in London, was evacuated to the countryside. Images of young bewildered faces, address labels attached to their lapels, grouped together like sheep at the main railway stations must have been a heartbreaking sight for any parent. But Wolff wasn’t sent off like this. He was seated in the back of his father’s Wolsey car, for the long journey to Torcross in Devon.

Here he was left, aged five, to attend boarding school far from the sound of the London blitz, and conversely with London far from the sound of the many beatings he would receive from the teachers who inhabited this frightening new home. He remained there for three years, only seeing his parents during the holidays. He recalls never returning to the same home twice as his parents were constantly on the move. This, coupled with their divorce and the introduction of a stepfather, must have e e made a very unsettling foundation at such an impressionable age.

Wolff was a sensitive child with a natural affinity with animals, which many years later would become an inspiration in his professional life. He remembers while on holiday in the 1940s being so concerned about a group of seaside donkeys, which seemed to have such a depressing life, that he contacted the RSPCA for help.

Academically he was, as he puts it, ‘a dunce’. At a common entrance exam he was so frustrated at not being able to understand any of the questions, that he stood on his desk and tore the paper up in front of everyone. He was put through a crammer and somehow managed to scrape into Gresham Public School. Once again he was immersed in a claustrophobic, monotonous regime. He would exercise his imagination by altering the look of his school uniform to create a sense of current fashion or would simply gaze out of the window to watch leaves falling to the ground.

At 17 years old he left and spent a year in France. While there, he became passionate about church architecture. This interest led him to apply to the Architectural Association School in London. He’d also read The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand and thought that the life of an architect sounded romantic and might be the perfect way to attract girls. He quickly discovered this was not the case. The work was extremely hard and because of Wolff’s extraordinarily youthful look – he was 18 but would pass for 14 – no girls were forthcoming.

Eventually and inevitably he got thrown out of the AA. He drifted for a while, spending a great deal of time at the London Film Theatre, soaking up French films and smoking Gauloises while trying to emulate Jean Gabin. At the suggestion of an AA tutor, he applied to Hammersmith School of Art. Here he dabbled a bit in fashion design and interiors. He arrived home one day to find a brown envelope waiting on the doormat. It was his call up papers for compulsory National Service.

The experience was to be a nightmare for Wolff. He had endured oppressive regimes at boarding school, but nothing had prepared him for this. He put all of his efforts into the aesthetics of the army where he would make a special point of having the most immaculate e e uniform, but he loathed the outrageous discipline. He resisted and rebelled, which got him into constant trouble, and he was confined to barracks on many occasions. He was eventually discharged for being an unsuitable character for the army.

Approaching 22 with no qualifications other than a little design knowledge, he found a job at Olympia working on exhibition stands. This was the beginning of a string of short-lived jobs, designing anything from nightclubs to light fittings. This latter pursuit got him involved in overseeing the manufacturing process and for the first time exposed him to the process of taking an idea and converting it into reality.

His first long-term job was with the design department of Crawfords Advertising. Wolff was employed as a general designer, under the watchful eye of Jack Foxell who was to become a mentor to him. He stayed at Crawfords for three enjoyable years. From there he moved to the BBC working as a set designer, but became quickly disillusioned, being more excited at seeing the work of the television graphics department. In 1962 he freelanced for a while and from the proceeds bought a magnificent Citroen DS21. He had fallen in love with the way the French had a more eccentric take on things and his car seemed to epitomise this.

In 1964 he joined forces with James Main, a designer looking to expand his consultancy, who had noticed Wolff’s work. It was here that Wolff was able to develop his philosophy of an inclusive form of design, thinking carefully about the journey through various parts of a company and being sensitive to the varying quality of that experience. This became the cornerstone of Wolff’s approach. A little later Wally Olins joined the company. On meeting him Wolff recalls thinking that here was a proper grown up, brimming with qualities and experience. Wolff Olins was born. The rest as they say is history.

Or is it? Yes, Wolff Olins was hugely successful and influential and grew rapidly. But he admits now that much of what he believed about embracing the totality of a client’s business was rarely achieved there, and much of the work, although award-winning, did not go deep enough for him. There were exceptions – Hadfields’ paints, which used a characterful fox to represent the company, was one of the great identities of the 1960s and trail-blazed a departure from the abstract Swiss graphic symbolism popular at that time. This was the beginning of Wolff’s introduction of all creatures great and small into his work.

Due much to Wolff’s vision and Olins’ business acumen the company prospered, but Wolff became dissatisfied with the work and with his own persona. At the suggestion of a friend he attended a four-day course with the controversial Erhard Seminar Training movement, an intensive programme of self-discovery. The effect was to be dramatic and lasting. He recalls, ‘It changed my life and gave me permission to be myself.’ It was followed by a more advanced course in the US.

But this newfound liberation was to play havoc with the well-oiled wheels of Wolff Olins. He began to alienate his fellow directors who did not share Wolff’s revised philosophy and desire to change things. In a well-documented boardroom coup Wolff was unceremoniously dispatched. The hurt of this incident is still betrayed in his eyes.

Post Wolff Olins he formed The Consortium – a loosely based collective of, as Wolff puts it, ‘the very best people’ with Wolff acting as conductor. Its symbol, a goldfish, endorsed the sprit of an open and transparent company. Three years on, he disbanded the company to join Allied International, and then moved to its parent company, Addison, as ‘creative supremo’. There he found so much travelling and arms-length creativity that he became frustrated and left.

In 1992 he took over from Dick Gyatt as external design manager for WH Smith – a post he loved for its penetrating insight into a retail giant. Not long after, he slipped into a simultaneous roll as non-executive director of Newell and Sorrell. Although there primarily to give advice on the growth of the company, his creative influence was very evident in the Niceday identity, which introduced a quirky little spotted dog to give a sense of fun to the anonymous world of stationery.

All good things come to an end. Boardroom changes and an economic downturn at WH Smith meant the end of Wolff’s services there.

In 1998 he formed The Fourth Room, which Wolff describes as ‘the first real radical company’. As its ‘director of imagination’ he has surrounded himself with like-minded people and at its heart is a determination to do things differently. No physical design takes place at The Fourth Room; all graphic work is done by a loose partnership of selected consultancies. The Fourth Room’s prime function is to help companies define their vision, often looking many years ahead.

When I met with him, he had just returned from the US where he is helping MFI to undergo a major cultural change to the company. Our talk was interrupted by Lucy demanding to be let out. She stood up, stretched and slowly walked towards the door. What was odd is that Lucy only has three legs. But in Wolff’s eccentric world it somehow seemed right.

Approaching his 70th birthday he can reflect on a full and rewarding professional life; the first designer to be president of British Design & Art Direction, president of the Chartered Society of Designers, a string of prestigious awards, a pioneer of a holistic approach to identity design, and an uncanny ability to always get the best out of people.

Where others might opt for a diet of daytime television and perfecting a cynical bitterness towards youth, Wolff retains a child-like sense of wonder at the world. He smiles a lot, positively relishes the daily challenges set by The Fourth Room and still finds himself gazing out of the window to watch leaves falling to the ground. m

Mike Dempsey is chairman and founding partner of CDT Design

-

Post a comment