“A manifesto for ideas – for content over mere decoration”

Patrick Argent reviews the recently released updated edition of A Smile in the Mind and makes a case that design needs more witty thinking and substance over style.

The late US designer Paul Rand, commenting in 1994 on his disaffection with the direction of contemporary graphics, stated unequivocally in his book Design, Form and Chaos: “The absence of restraint, the equation of simplicity with shallowness, complexity with depth of understanding and obscurity with innovations, distinguishes the work of these times.”

Two decades ago, the original version of A Smile In The Mind was a refreshing antidote to the increasingly style-driven vacuity prevalent in much of design, which Rand had so vehemently railed against.

Gloriously free of commercial dross and liberated from the stranglehold of conforming to the pervasive dictates and vagaries of fashion, Beryl McAlhone and David Stuart’s volume presented an unusual thematic catalogue of design, which featured work from many of the masters of 20th century design thinking.

In essence, the book celebrated the application of humour as a category of design very much in its own right. The premise being that the idea was absolutely everything, being judged objectively for its validity in communicating, by the ability to raise a knowing smile from the viewer. It reflected both visual communication in its purest form and for many designers of previous generations, the epitome of graphic design as an enduring and substantive high art form.

In this updating of the 1996 version, it is apparent that despite having become even more deeply unfashionable over the past 20 years, this cerebral and exuberant approach to design is thankfully not extinct.

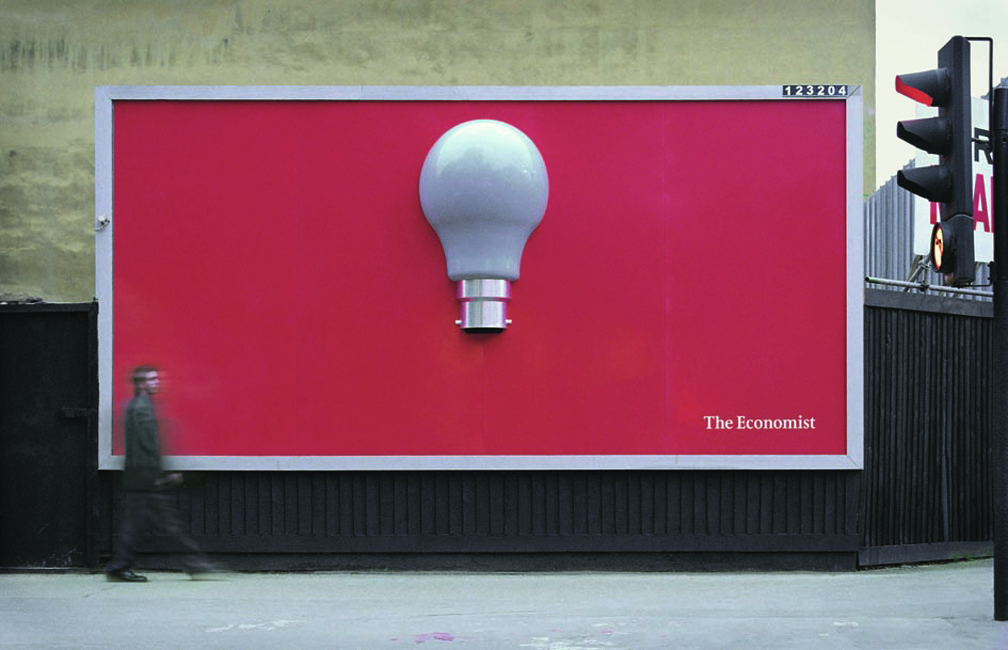

However, although amply illustrated with many more contemporary examples throughout, there could be an argument for stating that there is a distinct scarcity of such ideas in graphics today overall. When was the last time you saw a truly great witty idea in a poster or logo in the street that compelled you not to only look twice but also made you wish that you had designed it?

Repeating the essential format of the book, although with an unexpectedly lurid day-glo cover, the new edition also retains much of the literary content and layout of the first volume, adding other essays, further expanded with numerous more recent additions to the impressive inventory of design examples.

Many of these add surprise to the array of previous ideas and display an expansive flexibility and intriguing scope in the variety of applications in terms of scale, medium and jobs. Lateral creative forays into three-dimensions, notably examples of advertising billboards, sculpture, art installations, automotive design, product design and even architecture, all find fitting inclusion in expressing the singular power of the witty idea.

With such a concentration of design all stemming from a particular approach, this interestingly emphasises the common denominator. The idea acts as the visual bond that links seemingly disparate, unconnected designs from differing eras and disciplines, allowing them to sit naturally together in context on the page.

This unity is further enhanced by the inherent timeless nature of so many of the examples portrayed, where it is difficult to estimate accurately as to what year or even decade exactly they were produced in.

True content, visual coherency, economy, relevance, meaning, design philosophy, integrity, clarity of communication, memorability, distinctiveness, intellectualism, engagement with the reality of the world and the unexpected swashbuckling adaptation of the familiar, are all aspects of the art of lateral thinking in design.

Eschewing the lemming-like obsession with style so ingrained within much of the industry both in 1996 and now, the book vibrantly reinforces the manifesto for the supremacy of ideas, of content over mere decoration, of objectivity over passing visual fads and of the designer’s core passion to truly communicate with the viewer.

This is design that has always allowed the designer to speak directly through the idea in an unambiguous, honest visual language, upholding a respect for the intelligence and intuition of the viewer.

Intrinsic within the subject matter itself is that of humanity and, perhaps not originally intended by the authors, the immediacy of accessibility of what is fundamentally a niche text, also presents itself as an entertaining populist book on design to a non-specialist audience.

A valuable accompaniment to the initial text, this follow-up volume establishes itself as a separate entity but also authoritatively extends and enhances the original in the generous distribution of new material throughout.

Twenty years later and well into a new century, the second A Smile In The Mind emerges far above the glut of transient, on-trend graphic design publishing of recent years.

This new revision, a richly expanded and absorbing compendium, is a further resounding testament to the enduring capability, versatility and potency of the witty and sharply-crafted graphic design idea.

The new, revised edition of A Smile in the Mind: Witty Thinking in Graphic Design, by Beryl McAlhone, David Stuart, Greg Quinton and Nick Asbury, is published by Phaidon and available now.

The Netherlands, 2007. Courtesy Studio Florentijn Hofman

-

Post a comment