“There is a snobbery about postcards”: British Museum explores overlooked art form

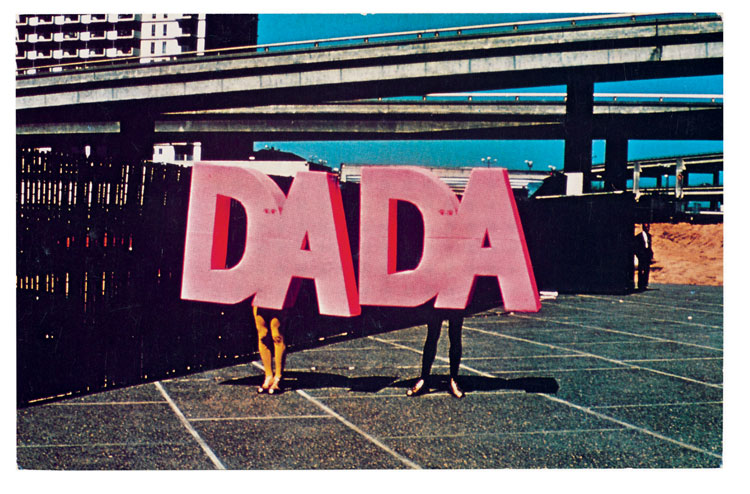

A new show at the British Museum features 300 artists’ postcards from the last 60 years, which look to demonstrate the political power of the little prints, and how they have helped to “democratise” art by breaking away from gallery culture.

Long gone are the days where postcards would be used widely to communicate with and keep in touch with people. But the little 15cm x 10cm rectangles still serve a purpose, whether that’s to form a collection of mementos from various holidays, or to surprise someone with a piece of post when they need cheering up.

But to what extent do we see these small rectangles as artworks in their own right? While museums and galleries will often shrink down famous David Hockney and Pablo Picasso pieces to fit the reduced size format and bulk sell in their gift shops, postcards can also be the original canvas for art; many artists and designers throughout history have used their small size and easily dispensable quality as a way to share a message or raise their own profile.

The British Museum is exploring the versatile art form through its new exhibition The World Exists To Be Put on a Postcard: Artists’ Postcards from 1960 to Now.

The show features 300 postcards made by artists over the last 60 years, donated to the museum by writer and curator Jeremy Cooper, who has spent the last 10 years collecting roughly 1,000 postcards from various means, including online marketplaces and real-life flea markets.

His collection has been whittled down by himself and the British Museum curatorial team to 300 pieces, including original artworks by famous names such as Tracy Emin, as well as those by lesser-known, “avant-garde” artists who are radical and experimental in their approach.

By showing a broad range, the exhibition aims to show the “democratising” nature of the postcard, says Jenny Ramkalawon, curator at the museum and co-curator of the show. This led to the decision to create a giant “pinboard effect” for the exhibition space, with postcards pinned to boards and “scattered” in display cases, rather than “mounted reverently”, she says. The design of the space has been completed in-house.

“We didn’t want to give the postcards a ‘museum feel’, or make them inaccessible,” she adds. “Anyone can collect postcards. Many of these, even the ones by famous artists like Joseph Beuys, you could pick up for a few pounds, whereas there was no way most people could go to an art auction and get a full-size artwork from the same artist. Jeremy [Cooper] was fed up by high prices in the art world.

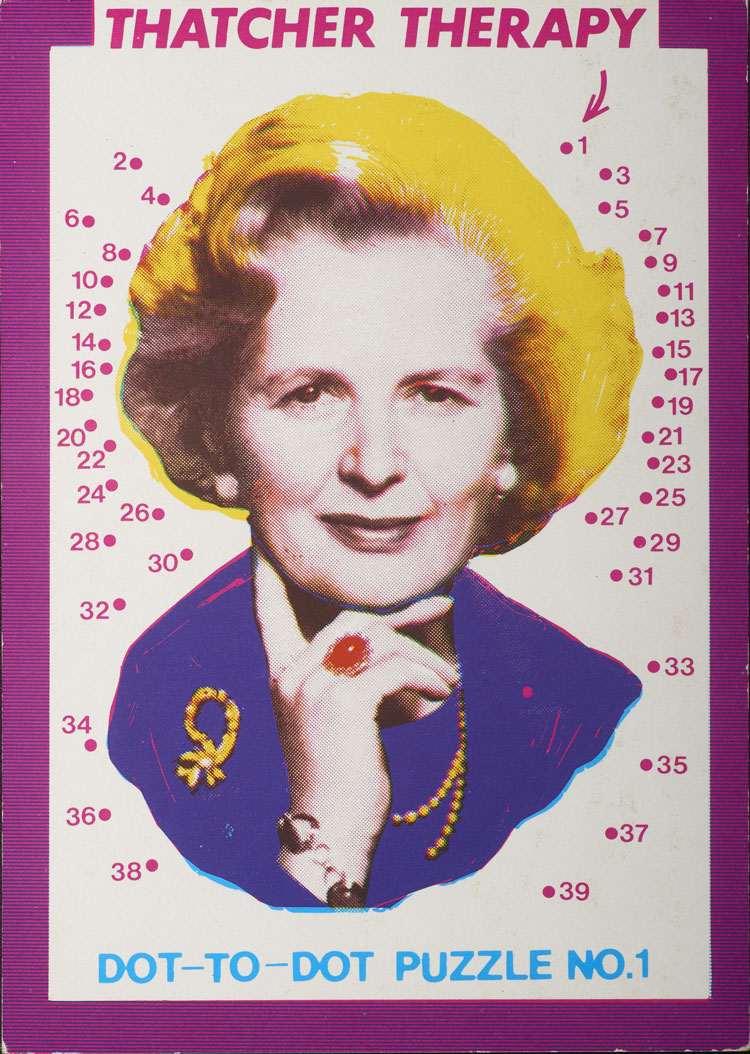

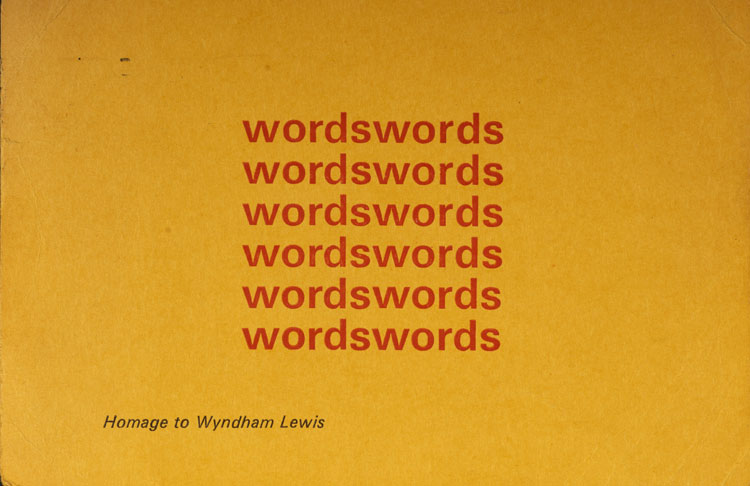

The ramshackle display of the postcards in the exhibition also looks to reflect the experimental nature of the art that has graced them over the decades. The ability for postcard artists to spread subversive, political messages was made easier by the fact that they could be easily disseminated and shared by post, says Ramkalawon, while avoiding the need to be approved by a gallery or museum meant the art was both more accessible and could be more radical.

“Their accessibility has made them incredibly effective as political tools,” Ramkalawon says. “They’re small, cheap, and could be easily swapped between friends.”

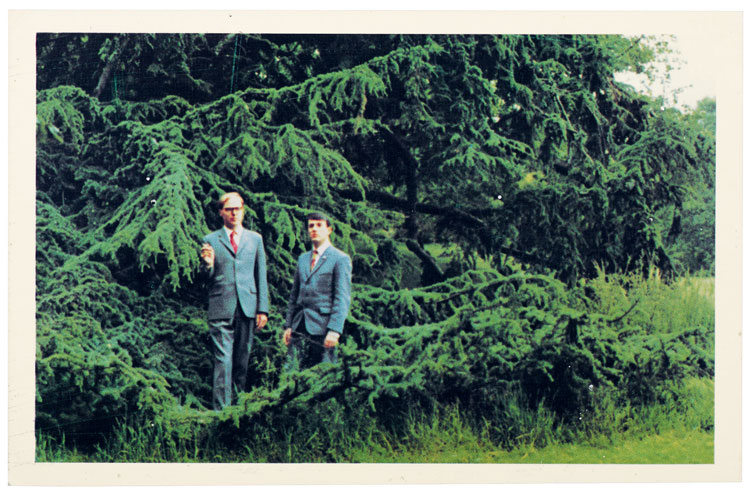

The exhibition is split into 15 thematic sections, including political postcards, feminist postcards, fluxus (experimental, performance-based) art postcards, and postcard invitations, so those that were sent out to advertise or promote an event, gallery opening or talk. Other sections include graphic and letterpress postcards, and portrait postcards, which feature portrait photos of artists.

The idea joining all the postcards together is that they are works of art in their own right, says Ramkalawon, and had the intention of being sent via post rather than hung up in a gallery space.

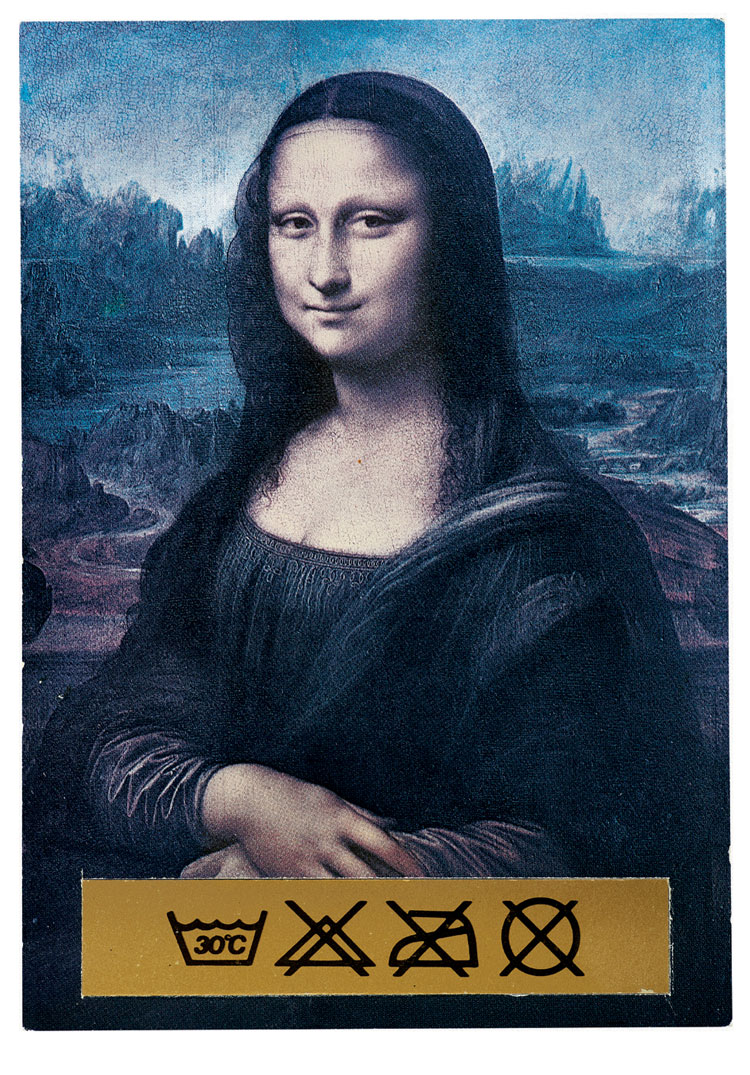

“The core of the exhibition is that these postcards were original artist concepts, rather than shrinking the Mona Lisa to fit,” she says. “These are not the kind of things you buy in a museum shop.”

One experimental postcard that features in the show is Postman’s Choice, a witty piece by artist Ron Gauthier, which includes an address to one person on one side of the postcard and an address to somebody else on the other side, leaving the decision of where to send it up to the person delivering the post. Featuring in the fluxus section of the exhibition, this art movement focused on experimental art performance, with the emphasis on the process and undertaking of work rather than the final product.

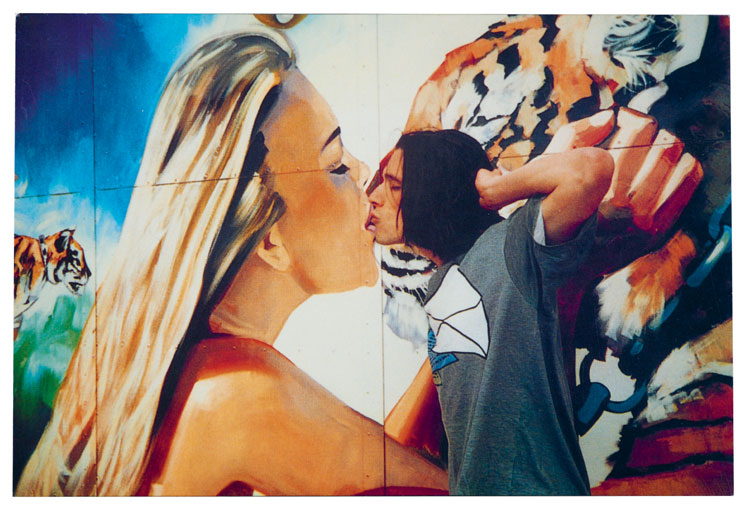

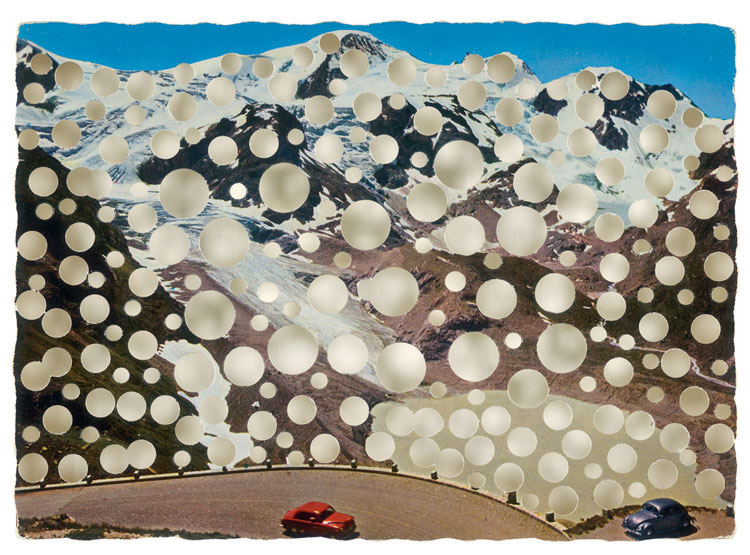

Feminist examples include Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots, which documented her trip around California, where she bought and photographed 100 different Wellington boots in various locations, producing 100 separate postcards.

Politics is represented through multiple depictions of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan from the 1980s, Photo Op, a piece by Peter Kennard and Cat Phillips showing Tony Blair taking a selfie against an image of burning oilfields, and Art for the Moratorium, an anti-Vietnam war postcard by Jasper Johns.

Ramkalawon says that while the postcard has the capacity to be very subversive, given how easy it is to share, for this reason it has also been devalued as art and treated as more disposable than traditional gallery work.

“It has been overlooked as an art form,” she says. “There’s a real snobbery about this kind of ephemeral art, like there has been with Christmas cards and lottery tickets. But they offer viewers so much about life in the 20th and 21st century, from its political climate to people’s interests and concerns.”

She adds that, despite their effectiveness, certain types of postcards are increasingly dying out — while artists may continue to create work in the format, certain uses, such as invitations, are becoming obsolete as email invites take over.

“Some of the invitation postcards we have in the show are rare, because often they are just discarded after someone’s been to a gallery opening,” says Ramkalawon. “But they often have really interesting contextual and historical information on them about the exhibiting artist. They’re incredibly informative.”

She adds that, while postcards may continue to exist, traditional techniques for producing them may also become non-existent.

“It’s becoming more difficult to find people who make postcards, such as lithographers,” she says. “Instead, the images are all becoming digital. I feel true postcard art has come to an end, but I’m happy to be proved wrong — there are some younger artists still using them in their practices.”

What sets the postcard apart from gallery art is that, while art within its own right, it was once used prolifically as a means to communicate and share information. As digital communication takes over, it could be that the postcard becomes less useful in conveying a political or social message – particularly when people’s thoughts can reach millions of people across the world via social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter.

For this reason, the British Museum hopes to immortalise Jeremy Cooper’s postcard collection, and reserve the individual pieces as reminders of various artistic movements, and different social and political climates. The show also hopes to show visitors the extent of the British Museum, emphasising that it devotes space to contemporary and avante-garde art, as well as history.

“Postcards are a snapshot of history, which is why I think the British Museum is a great place for them,” says Ramkalawon. “I hope this show will show visitors the diversity of our collections, and the artists we collect.”

The World Exists To Be Put On A Postcard: Artists’ Postcards from 1960 to Now runs until 4 August 2019 at Room 90, the British Museum, Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, London WC1B 3DG. Entry is free. For more information, head here. Following the exhibition, the collection of postcards will be kept in the British Museum’s archives, and can be accessed and viewed by visitors by booking an advance appointment.

-

Post a comment