Goodge Street glory

Designers write better than writers design. Several designers and illustrators have been masters of the pen – Ashley Havinden, Hans Schleger, Osbert Lancaster, Abram Games, Milton Glaser, Terence Conran, Alan Fletcher (I’ll no doubt think of others).

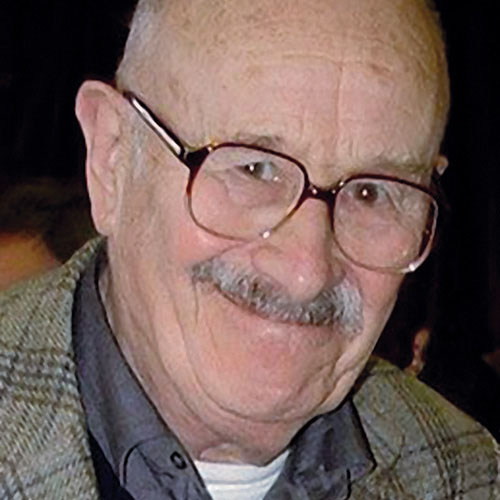

David Bernstein hung out in the studio next to Michael Peters back in the fledgling days of design. These days, he admires his lucidity most of all

Designers write better than writers design. Several designers and illustrators have been masters of the pen – Ashley Havinden, Hans Schleger, Osbert Lancaster, Abram Games, Milton Glaser, Terence Conran, Alan Fletcher (I’ll no doubt think of others).

Edging into this company is Michael Peters, to judge from his reminiscence (A lost world, DW 26 March), in which he evokes a past age of design studios pre-Mac. You can almost feel the Spraymount beneath your feet.

The tools of the trade Peters lovingly revisits were also my own though, for the most part, only vicariously. Writers have no equivalent venerable tool box. My typewriter may have morphed into a computer and research may have become easier on the Web but, overall, technology has not made the writer’s task that different.

Peters’ piece resonated not just because I observed the changes he chronicles from adjacent offices, but because I did become physically involved, first with a planned induction into advertising life and subsequently when I emerged from the big agency world into the hands-on environment of a small start-up. I too became obsessed with type books and typefaces. I was made to cast off, and I even spent time beneath the hood of the Grant enlarger in the building in Goodge Street where our start-up started. We were lucky in our landlord, a generous 29-year-old Peters who had, not long before, set up Michael Peters and Partners, having left Collett Dickenson Pearce and a later partnership with Lou Klein.

I watched him at work. Our views were similar about the relationship of advertising and design, and that of creativity and business. So it was no surprise when he helped set up the Design Business Association and much later instituted, at the Royal College of Art’s Helen Hamlyn Centre, the Michael Peters Awards for Interdisciplinary Collaboration.

We were at one in breaking barriers, and I wonder what would have happened had I remained his tenant. But a space became available in Regent Street, six floors up in rag-trade territory. Another acquaintance, Terence Conran (call me a design groupie), redesigned the workroom. All green baize and gloss white, it looked as if a billiard hall had mated with a clinic.

Conran and Peters both asked awkward but pertinent questions, often about one’s philosophy. James Thurber suffered something similar at the New Yorker when he worked under the iconic editor Harold Ross. His technique, wrote Thurber, ‘succeeded in refreshing your knowledge of yourself and renewing your interest in your work’.

I’ve followed Peters’ career and respected his lucidity when expounding his credo. He rarely has recourse to marketing-speak or complex language. It’s simplicity at all costs, deceptively so, for I guess he shares John Ruskin’s belief that ‘it is far more difficult to be simple than complicated’. Here he is explaining design’s key role in global marketing: ‘People understand pictures more than they understand words.’ Later in the same interview (New York Times, 1989) on the overlap of design and advertising: ‘Design is permanent media.’

Peters was an early evangelist for design’s place at the heart of the product: ‘It’s not graphic frivolity any more … it’s within the product itself. It’s about creating a better product.’ Lost worlds are OK, but new worlds are yet to be won.

-

Post a comment