New book draws back the iron curtain on the Soviet Union’s little-known design history

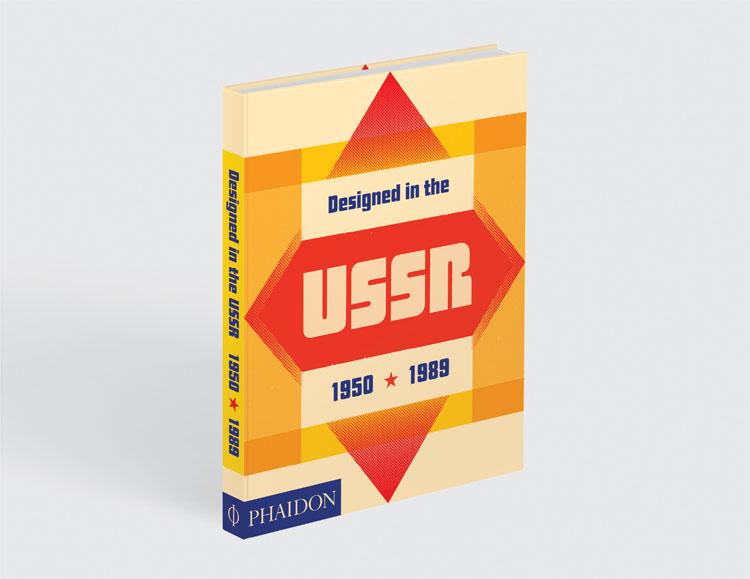

As Phaidon releases a new book featuring over 300 Soviet products and other designs dating from the 1950s, we speak to Moscow Design Museum founder and director Alexandra Sankova about how the book came about, and the importance of preserving rare historic designs.

It’s hard to believe that the word “design” was banned in the Soviet Union until as late as the 1980s. After the Second World War, the design industry was booming in Western countries such as the US and UK, where the work of designers was both encouraged and recognised.

Designers in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) however, remained anonymous and uncelebrated. Living in a socialist society meant that there was no need to glorify the work of individuals, and designers – or “artistic engineers” as they were known at the time – worked for the collective good of the state.

Following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, the state-controlled industrial sector swiftly followed suit and a huge number of official documents were either destroyed, censored or lost. As a result, design in the Soviet Union has up until now remained a little-covered subject by historians. Publishing house Phaidon is hoping to change this with the release of its latest book, Designed in the USSR. Dating from the post-war period in the 1950s right up until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the book is one of the first of its kind to explore the design history of this era.

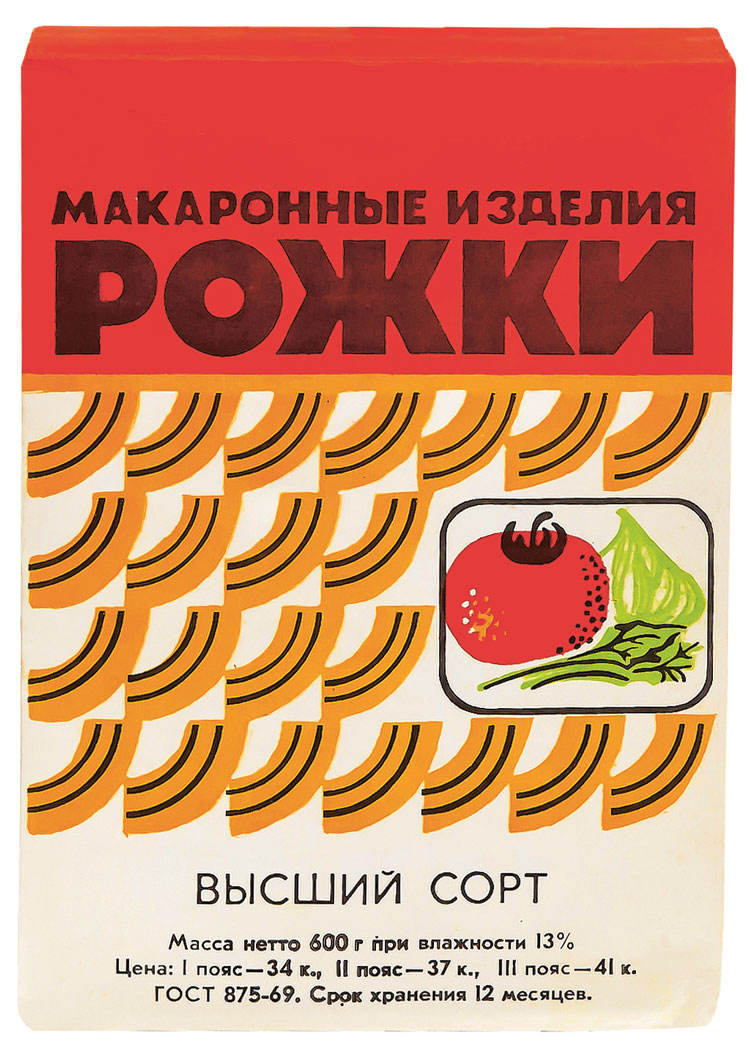

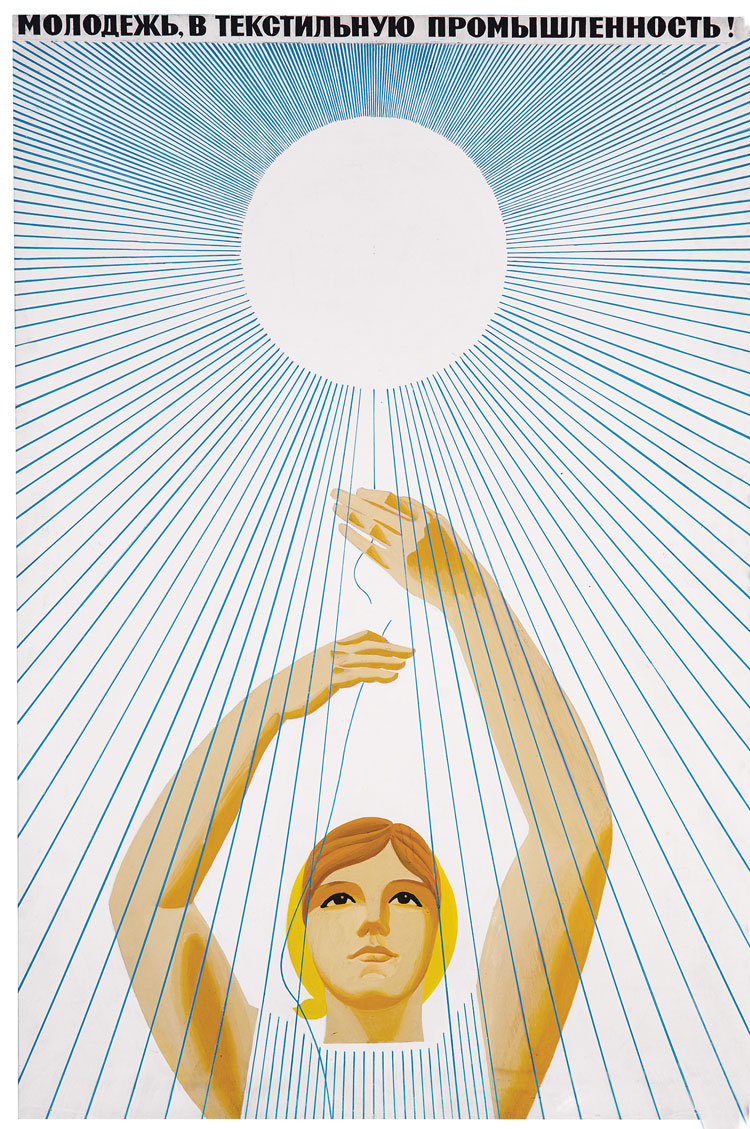

It showcases over 350 images of products, graphics, fashion and other ephemera, each of which offer a snapshot of what life looked like for millions of Russians living under Communist rule. Featured designs range from space age-inspired razor packaging and sweet tins adorned with illustrations of rockets, to a “social awareness” propaganda poster encouraging young people to “go to the textile industry” for the good of their country.

All the artefacts featured in the book have been drawn from the permanent collection of the Moscow Design Museum. Founded in 2012, the non-profit institution is the first museum in Russia specifically dedicated to design, and has gradually been building up its collection over the last six years. “After the Soviet collapse, my friends and I started to travel around a lot,” says the museum’s founder and director Alexandra Sankova. “I realised that almost every country I visited had a design museum, and we were the only exception. So I decided that I wanted to highlight the people that had built our environment back in Russia.”

The book is split into three chapters, each focusing on a different aspect of daily life. Citizen features consumer products that were used by Russians day-to-day, such as the popular Avos‘ka string shopping bag. The name was taken from the Russian word avos’, meaning “just in case”, as a nod to the fact that the bag was convenient to have at hand in case people spotted scarce or valuable goods while they were out. The second chapter, State, focuses on the state-controlled aspect of everyday life, and largely features products such as portable TVs that regularly spewed out propaganda and a dial-less phone that provided a direct line of communication between high-ranking employees and party officials. Finally, World looks at the country’s place within the wider socio-political picture, with designs including Misha, the Russian bear mascot for the 1980s Moscow Olympics and Saturnas, a spherical vacuum cleaner based on the iconic Sputnik space satellite.

By showcasing these designs in the context of the period in which they were produced, the book goes some way in dispelling commonly-held misconceptions about life in the USSR. Particularly, as writer and curator Justin McGuirk points out in the book’s foreword, that the Soviet experiment was as much a cultural failure as it was a political one. “According to this view,” McGuirk writes, “the tedium of Soviet consumer goods was a fatal flaw in the system, grinding down morale and stoking the desires of the Russian citizen for blue jeans and other trappings of American-style consumerism.”

Despite the ideological existence of the iron curtain, Soviet designers were in fact very well informed about what was going on in the world, according to Sankova. In 1962, the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union ordered the creation of the All-Union Scientific Research Institute for Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE), with the aim of regulating the design profession and improving the quality of mass-produced industrial goods. Its monthly journal, Technical Aesthetics, featured the latest trends and developments from around the world, and Russian dignitaries would regularly visit places like Europe and America to meet with design councils and see other designers’ studios. The Saturnas vacuum cleaner is a good example of the West’s influence on the Soviet aesthetic; its design was largely based on American company Hoover’s similarly spherical model, Constellation, which was released several years earlier.

While the nature of the state’s political system dictated which designs went into production and which ones were deemed too frivolous, Sankova points out that there were some benefits to Soviet-designed products, such as their sustainability. “Back then everything in Russia was very rational, so the focus was on the function and durability rather than aesthetics,” she says. “They didn’t have glossy advertising, so the goods didn’t need to be so attractive.”

The book certainly gets the reader to think twice about any preconceptions of what life looked like behind the iron curtain, but its real significance lies in preserving a little-documented period of history before it disappears entirely from our collective memory. Since it first opened six years ago, the museum’s collection has grown enormously thanks to donations by everyone from designers and professors to members of the public who happen to visit its permanent exhibition. “We went from suggesting that we should make an exhibition catalogue, to the collection increasing so dramatically that we decided it can’t just be a catalogue,” says Sankova. “It’s so much more than that now”.

Designed in the USSR: 1950-1989 costs £24.95, and is available from Phaidon.

-

Post a comment