Theresa May triggers Article 50: how will this affect designers?

The official Brexit process has begun, and the UK has until 29 March 2019 to leave the European Union. We look at how some of Theresa May’s promises will impact on the creative industries.

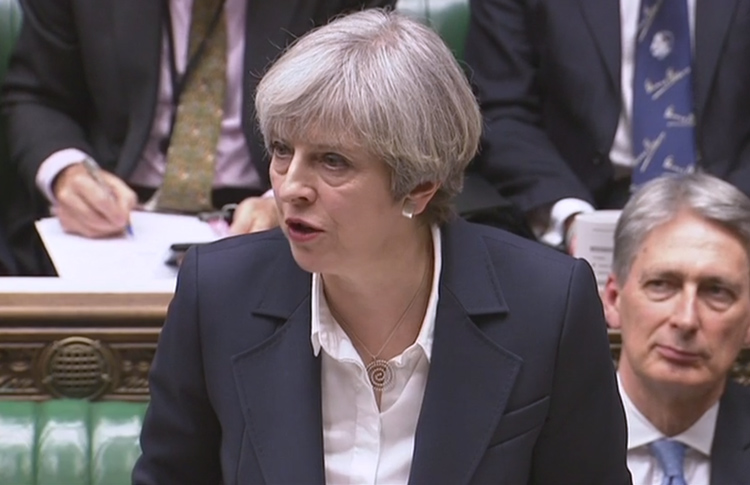

The process of the UK leaving the European Union (EU) has officially started, as prime minister Theresa May has triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty.

In handing over the UK’s resignation letter to European Council president Donald Tusk this morning, May has started the two-year countdown in which she must negotiate the terms for the UK to leave the EU.

A “truly global Britain”

May relayed the plans she first set out in January again today – the need for a “truly global Britain”, which “reaches beyond the borders of Europe” but retains a “special relationship” with the EU.

May has reiterated that the UK will no longer retain membership of the European single market, which allows free trade and movement of people between countries, but will strike a new bespoke deal with the EU.

The “brightest and best” international talent

She spoke of the need to attract international talent – the “brightest and best” – and said that securing the right to stay for EU citizens currently living in the UK would be a priority.

But May also spoke of the need to control immigration, and ensure British sovereignty, meaning that British citizens will no longer be subject to – or protected by – European law.

Laws will be decided in Westminster, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, rather than the European Court of Justice, which May says will give “devolved administrations a significant increase in decision-making power”.

While she wants the UK to have control over its borders and its laws, she wants to continue to work with the EU on developing science and tech innovation and research, and pledges to “trade with the EU as freely as possible” despite not being part of the European single market.

Analysis

May’s speech at the House of Commons today was met with heckling at points – particularly when she condemned the “protectionist” state the world was in and pledged to create a more “global” Britain and protect the status of EU expats currently living in the UK.

The stricter curbs on immigration that will come with losing the European single market – and so the free movement of people – could mean the UK design industry is impacted. Research shows that 6% of creative industry jobs in the UK are taken up by EU workers, while 5% are taken up by non-EU migrants.

May says she wants to continue to attract the “brightest and best” to study and work in the UK, but it’s unclear at this point how this will be judged.

If the Conservative Government’s preference towards science, technology and maths in terms of funding and education is anything to go by, it’s not likely that design will be seen as a top priority; except perhaps where product and digital design crosses over into the engineering and software development fields.

Do designers earn enough to be “brightest and best”?

New rules coming into force this April also require non-EU immigrants who wish to settle in the UK permanently to earn at least £35,000 per year. This could mean that once the UK officially leaves the EU in 2019, EU citizens may be considered in the same way.

The creative industries are not notoriously lucrative – Design Week’s Career Survey 2016 showed that half of designers surveyed earn less than £30,000 per year.

The most common salary bracket was £30,000-£40,000, which made up a quarter of designers surveyed, with the average salary being £36,500. The survey also shows that salary is likely to increase with experience, with the majority of those earning less than £20,000 having had less than three years’ work.

While designers may have more opportunities to hit £35,000 than other creative sectors, this implies that student and graduate designers would struggle to meet the requirements, if these same boundaries were set for EU workers.

Ambiguity around freelancers

This rule also suggests the need for a regular salary from a full-time job so could be to the detriment of the many designers, illustrators and creatives who work for themselves on a freelance or project commission basis.

A recent report shows that the UK accounts for a fifth of all creative industry jobs in the EU, suggesting that the UK is currently a desirable destination for creative workers from other EU countries because of job opportunities.

The Design Council also found that the UK has “the largest design sector in Europe”, which contributes £8.8 million per hour to the economy.

Creative skills gaps in the UK exist

If there is less freedom of movement into the UK, there will be less access to EU talent, which could result in existing skills gaps in the UK creative sectors widening – for instance, video game animators and visual effects specialists are two professions which are currently on the Government’s occupation shortage list, according to the Creative Industries Federation (CIF).

At the same time, the vast majority – 89% – of creative industries jobs are taken up by UK-based workers. Perhaps then the Government’s onus needs to be on encouraging and championing creative skills. But with the recent focus on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths) subjects, alongside the decision to cut design and technology GCSE from nearly half of all schools nationwide, it may need to rethink its approach.

The EU is the UK creative industries’ biggest export market

In terms of trade, the EU is the UK creative industries’ biggest export market, and received 57% of its total exports in 2014. Graphic design and product design are near the top of list of most exported goods and services, generating £226 million in 2014.

Research also shows that, in 2015, 44% of the UK’s total exports in goods and services went to the EU.

Reduced access to the European single market could impact the amount of work UK design consultancies get from clients in the EU, with Roger Mann, co-founder at exhibition design firm Casson Mann telling Design Week in January: “We get most of our public sector museum work from the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU). We have no idea what will replace the OJEU and how limiting that will be for us.”

Opportunity to expand into international markets

Equally though, there could be opportunity to expand into the international market, as pro-Brexiters such as James Dyson have implied. Dyson’s profits have actually increased since the EU referendum thanks to increased popularity of the company’s products in Asian markets.

But until stronger trading agreements with other non-EU countries are established, this is likely to only benefit big consultancies and companies with global offices and an existing international presence.

Leaving the EU also means the UK loses access to EU workers’ rights laws, which include equal pay, anti-discrimination rights and maximum working hours. May said that the UK will “build on” the rights we have been protected by, rather than abandon them entirely – but Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn retorted that loss of the EU’s protection could lead to the UK becoming a “low-wage tax haven”.

UK Government needs to create stronger copyright law

This could affect the working conditions of full-time designers, rather than the self-employed, who are less protected by workers’ rights anyway. More specifically to the design industry, the loss of EU law could mean less intellectual property and copyright protection, particularly design registration laws which give designers claim over originality.

Countries such as India, China and Brazil have far less stringent copyright protection, warns CIF – so if the UK is going to be trading more with them, the UK Government may need to tighten up on its own laws to prevent UK-based creative businesses losing profits to copyright infringers.

Yes, investment in science funds – but what about creative funds?

May has promised that the UK will continue to cooperate with the EU on science and tech research, so we assume she will prioritise continued contributions to funds such as Horizon 2020 – a €80bn science and innovation programme – in the future.

But what about funds such as Creative Europe, the European Commission’s €1.5bn cultural and creative programme? The UK is signed up to this particular fund until 2020, but whether the Government decides to renew its membership after that depends on whether it decides to invest more heavily in creativity.

Everything comes to an end. And there was never any assurance that the UK could maintain its leading position as a global creative hub. Britain’s creative industries enjoyed two decades riding the crest of a wave, powered by the capital’s perceived coolness and by the new brand thinking that Britons seemed so good at. But as it turned itself into the global buy-to-forget destination, London lost its mojo (and has become ‘overpriced, overrated and over there‘). And British branding has become very long in the tooth: more about cynical and often quite exploitative commercialism than the quirky and appealing creativity which made it famous. So the writing was on the wall for creative Britain before the EU Referendum, which really just made the problem explicit: the UK has become a grey, old, conservative nation with Middle England values, which doesn’t like foreigners and blames others for the loss of former glories.