The long-lost suffrage protest posters used to fight for women’s rights

This year marks 100 years since women aged over 30 were given the vote – Cambridge University Library is celebrating the occasion with a new exhibition showcasing previously-unseen political protest posters from the suffrage movement, which landed on its doorstep in 1910.

A brown, paper parcel had been sat within the depths of Cambridge University Library for 106 years before it was discovered. Finally unwrapped in 2016, the package – which was addressed simply to “the Librarian” and originally arrived at the university in 1910 – contained a colourful, humorous and shocking selection of political posters depicting women’s fight for equal rights in the early 20th century.

Now, 100 years after women over 30 finally got the vote in 1918, the university library has decided to showcase these previously-unseen protest design relics in its exhibition Our Weapon is Public Opinion: Posters of the Women’s Suffrage Movement.

The women’s suffrage movement officially began in the mid-19th century with the founding of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, but it was not until the 20th century that momentum really picked up nationally.

Emmeline Pankhurst founded militant group the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – the leaders of the Suffragettes – in 1903, and from there, more and more figureheads and groups started appearing.

While the hunger strikes, vandalism and bra-burning of Suffragettes such as Pankhurst are most commonly associated with the fight for equal rights, there were also many less extreme groups which lobbied Government to make constitutional changes. The more general term Suffragist was used to describe all members of the movement.

In 1918, the Representation of the People Act was signed and some women – those aged over 30 – finally got the right to vote. Cambridge University has fittingly chosen the centenary year to showcase its collection of original, suffrage protest art, which landed on its doorstep back in 1910.

The ominous parcel contained posters from a range of different women’s rights organisations, created by various illustrators and designers – but who sent it to the university in the first place?

It was Marion Phillips, a women’s rights activist and future Labour Party MP, says Lucy Delap, a historian and lecturer in modern British and gender history at the university.

This delivery was likely to have been provoked, adds Delap; a courtesy letter sat in the parcel, indicating that the university had requested these posters. The library probably made an active effort to contact women’s rights organisations, and ask them to send over their posters and pamphlets, so that it could keep a visual archive – and this documentation did not stop at feminist organisations.

“The library is full of anti-suffrage posters, too,” Delap says. “There were a lot of sexist feelings at the time, and there were anti-suffrage societies at Cambridge, founded by some very educated students. This will make another exhibition in the future, I’m sure.”

While there was a lot of support and sympathy for women’s rights in the late 19th century, particularly within Government, public opinion took a nasty turn when militant feminist groups started taking more extreme measures – resentment spread.

“The public saw the Suffragettes as an unfeminine, shrieking sisterhood, doing things like attacking Government ministers and putting acid in post-boxes. Activists were pelted with rotten eggs, vegetables and stones. There was a lot of sexism and misogyny.”

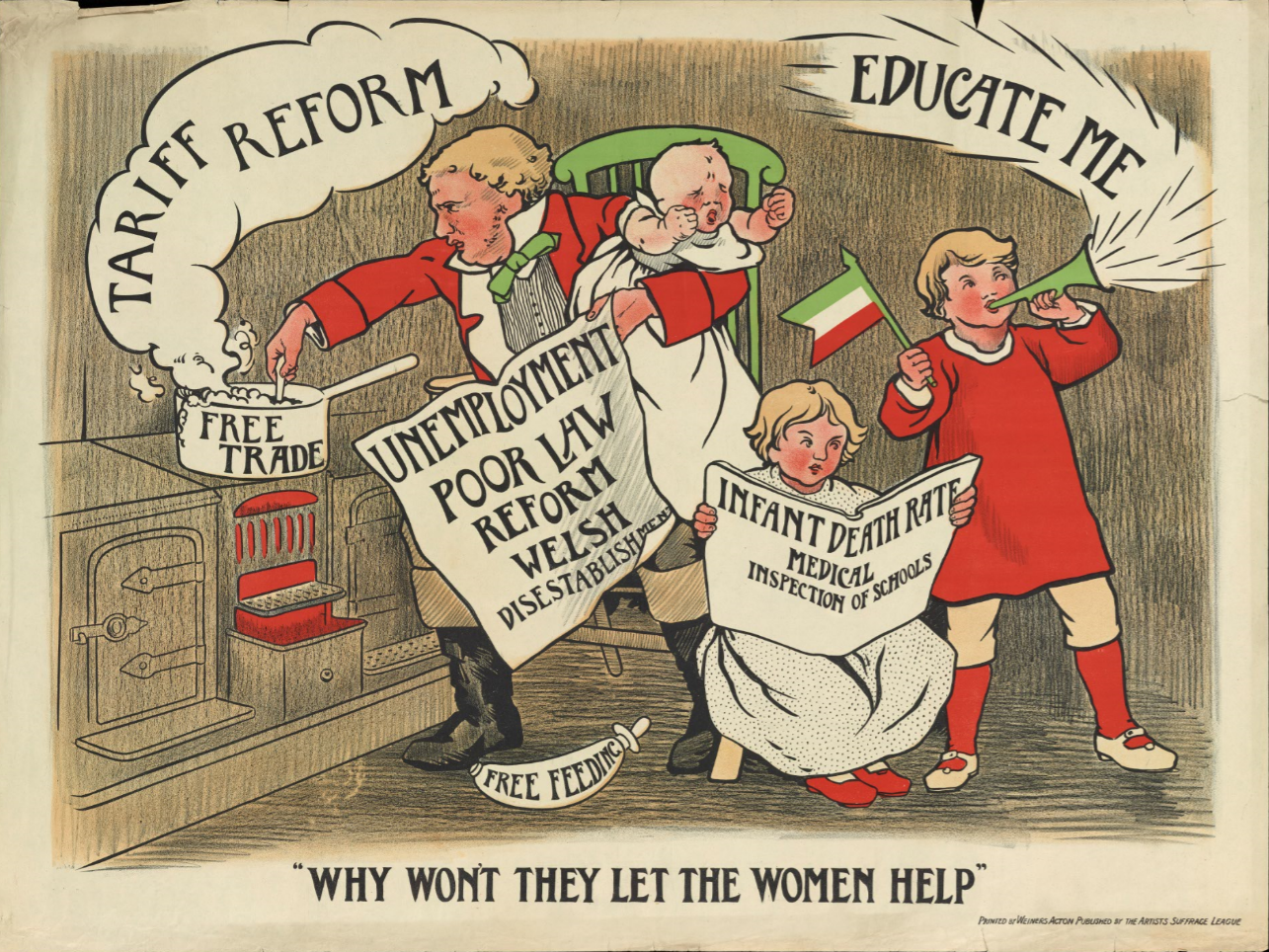

It’s no surprise then, that many of the suffrage posters from the era were seen to be angry and shocking. Others were witty and humorous, and mocked the feminists’ tormentors. Some were symbolic and aesthetically beautiful, and used the power of metaphor to get their messages across.

They were produced by feminists across the spectrum; the militant WSPU group that Pankhurst was part of, through to the constitutional law-abiding suffrage movement, and the Artists’ Suffrage League, a feminist organisation founded in 1907 by professional, female artists. The designers were men and women of all ages, including illustrator Caroline Watts, artist Emily Jane Harding Andrews, and modernist artist Duncan Grant.

Despite coming from different organisations, there are similarities in style and political message across the collection of posters, says Delap. They use fictional characters well known at the time, such as Mrs Partington, a famous, satirical, outspoken Conservative woman, and Mrs John Bull, a tongue-in-cheek female equivalent of the character John Bull – a fat, suited man that was meant to symbolise England.

The posters also use colour schemes associated with the different suffrage groups; red, white and green was used to depict the more “peaceful” or constitutional suffrage movement, while white, green and purple were the colours of the militants.

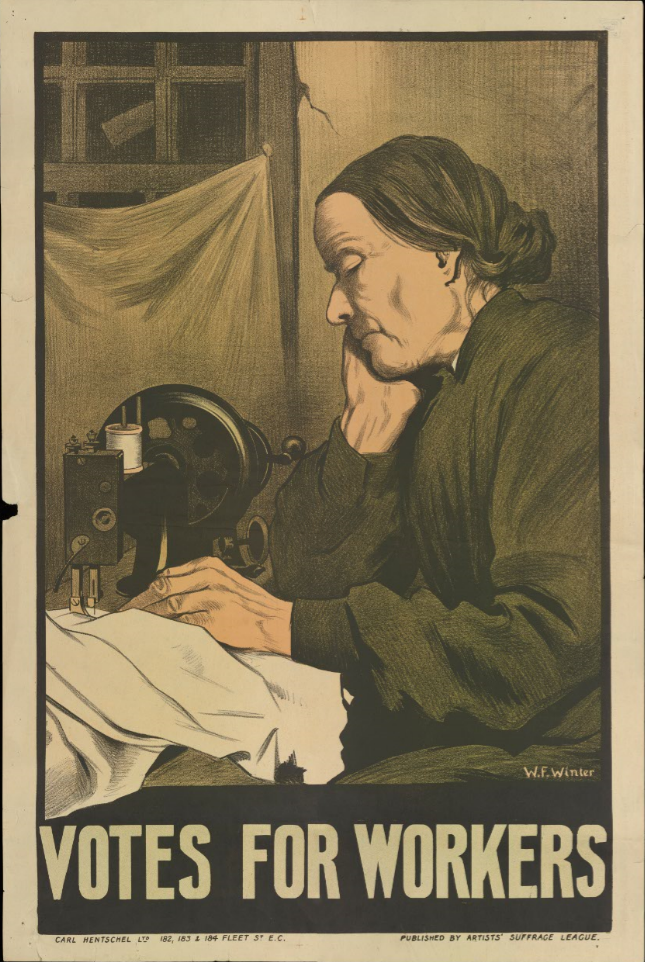

Another recurring theme, says Delap, is striving for something beyond the vote – the idea that the right to vote was not the only goal of the movement. Posters depict women as factory workers, university academics and more, to show how the movement would help improve working and education rights for women too. Fittingly, it was not until 1948 that women were allowed to become full members of Cambridge University, and graduate with full degrees.

Depicting women as workers also showed how the campaign was not limited to wealthy women, adds Delap. One poster shows a Lancashire cotton worker – indicated by her shawl – protesting at the fact that she has not been informed about changes to factory rules and regulations.

“There’s a beautiful contrast between the firey colours of her shawl and the grey in the rest of the picture, and the use of the woman’s vernacular speech against the sign,” she says. “It reminds us that the suffrage struggle wasn’t just about middle-class women – it was speaking for working-class women as well.”

Some posters would have been seen as shocking and disturbing. One depicts a woman being force-fed, referencing the hunger strikes that Suffragettes embarked on in protest. Viewers would not have missed the sexualisation of this image, says Delap, as a group of men force themselves on one woman. “These were shocking depictions of violence,” says Delap. “It looks like she is being raped. Some of these posters were very bold.”

Others take a more peaceful tone, and are “pastoral and beautiful”, Delap adds. One depicts “an attractive young woman” selling a suffrage magazine, set in pastel colours.

As stylistic and political message approaches differed in the posters, so did the techniques used to produce them, from printing press to wood-block printing to hand-drawing and colouring.

“Collections like this help us to understand how design can be used for a political cause,” says Delap. “They influenced women’s protest, and other protest, throughout the 20th century, such as the feminist posters of the See Red Women’s Workshop, which ran from 1974-1990. That poster tradition has carried on.”

While this exhibition is focused on the printed poster, this is not where political suffrage paraphernalia ended in the early 20th century. Postcards were handed out, magazines were disseminated, banners were waved at marches, and organisations even had their logos and brand colours printed onto merchandise such as teacups and pens.

“The suffrage movement was very interested in how to link colour schemes and logos with politics,” Delap says. “Really, it was at the forefront of visual branding.”

And we only need to look to social media to see that the suffrage movement’s witty, dry and brutal poster design continues to influence political movements today, she says.

“Whether it’s a hand-drawn poster in 1910, a zine in the 1990s or memes on Instagram today, images continue to be a really important part of political engagement,” Delap says. “A witty, speedy, visual response is still the best thing you can do to make a political point.”

Our Weapon is Public Opinion: Posters of the Women’s Suffrage Movement at the University Library runs until 31 March 2018 at Cambridge University Library, University of Cambridge, West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DR. Entry is free and open to all visitors. For more info, head here.

-

Post a comment