Growth oriented

China is busy building up its own design expertise in a bid to boost the economy. But where does this leave British designers looking for opportunities in this booming market? Jeremy Myerson reports back from Shanghai and Beijing

First came the Ming dynasty and the Qing dynasty. Now China is preparing for the Bling dynasty – or at least that is what the pundits would have us believe, as the world’s most populous country opens up consumer markets of unprecedented scale. But, before designers in the UK start salivating at the thought of rich commissions in such areas as retail, graphics, branding, product design and new media from the big Chinese urban centres, a reality check is required.

China is unlike other overseas markets. Already the manufacturing workshop of the world, its willingness to open up to foreign investment does not mean it will also be dictated to on the creative ideas front. In fact, in the long term, it does not want high-value innovation jobs elsewhere in the world to direct what goes on in Chinese industry. It wants those jobs at home, as the recent Cox Review of creativity in business explained, in a clear warning to the Treasury.

In short, China intends to become a design powerhouse in its own right. And, in its curious mix of a Communist political system that controls the advance of rampant capitalism, it has the means to make it happen with enormous speed.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t still room for British consultants with the right outlook and expertise. It just means the territory is squeezed and it pays to do your homework. Or, as Confucius says, ‘The expectations of life depend upon diligence; the mechanic that would perfect his work must first sharpen his tools.’

I base these observations on the findings of a recent trip to China as part of a Royal College of Art mission to build links with Chinese universities and other organisations in art and design. As Karen Cheng, a senior trade and investment representative at the British Embassy in Beijing, told us at the outset, ‘The Chinese are very ambitious about the creative industries.’

Nowhere is this more so than in Shanghai, one of the world’s fastest growing cities, with around 17 million people and a distinctly cosmopolitan outlook. As a port at the mouth of the Yangtze River, Shanghai has always been open to overseas influence. Now it’s moving fast to become a creative crucible as well as a financial and automotive centre.

At the newly-established Shanghai Creative Industry Center, director Dr Pan Jin explains that old factories are being freed up for creative clusters – entire districts comprising creative industry firms, with space allocated according to definitions borrowed for the UK Government’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport. Already 38 such clusters exist in Shanghai, each one accommodating up to 200 enterprises in design, architecture, fashion, animation and new media, as well as art galleries and antique warehouses. These clusters do not result from market effects; they are centrally directed by the Communist authorities running China’s wealthiest city.

At one of the best-known and most central creative clusters – the M50 Creative Garden, stretching over 500m2 – we find Chinese designer Qiong Er, who has set up the Visual, Environment and Product Design consultancy as a joint venture with French architect Jean-Marie Charpentier. Motorola heads the client list.

Symbolic of the city’s restless enterprise, Qiong Er not only has her hands full with VEP commissions, she also has a shop, a gallery and her own jewellery line. How does she pack it all in? ‘You don’t sleep in Shanghai,’ she explains with a shrug before rushing off to another meeting.

‘Working as a consultant in this market is a long game,’ explains Brian Ashcroft, chairman of Atkins China, the Chinese arm of the British design and engineering company WS Atkins. ‘It is no longer about gifted practitioners coming in to enjoy life for a short time to give the locals the benefit of their expertise. There is a fundamental shift to develop a design skill-base locally that is internationally competitive and can be exported.’

Atkins China, which has its headquarters in Shanghai, has grown rapidly from a handful of staff to more than 400, off the back of the goldrush boom in building, a direct result of command economy urbanisation. But Ashcroft believes that future growth will be more about design quality than just being in the right place at the right time.

‘New districts were built almost overnight, but regeneration of central Shanghai, for example, will proceed with more restraint,’ he explains. ‘The whole world is now in China and being visible is ‹ difficult. The next phase will be about raising our game, in terms of building local capability. British designers can’t just walk into this market and have the Chinese saying, “Thank God you’ve come.”‘

To meet Ashcroft’s thesis, much depends on China’s art and design universities to develop a design infrastructure to compete with international all-comers. But, in the country that invented paper and printing, progress in design education is now rattling along at breakneck speed. Many institutions rooted in a particular discipline are now widening their offer to reflect the needs of a more multi-faceted design industry. At Shanghai’s Donghua University – which is renowned for textiles, engineering, manufacturing and fashion design – environmental design and computer animation now figure in the curriculum. Across the city, Tongji University’s famous College of Architecture and Urban Planning boasts growing expertise in visual communication, transport and multimedia design.

Design courses are increasingly popular in China and vastly oversubscribed. ‘So many students apply that it becomes difficult to choose who to take,’ says Yonglei Ma, a lecturer at Shanghai Normal University. ‘The popularity is because design is not just about technology and business, it’s about people. It’s about the heart. That is important within Chinese culture.’

Design is also about sustainability, a subject that increasingly preoccupies the Chinese authorities – especially in Beijing, host to the 2008 Olympics, where pollution is so bad that targets have been set for ‘blue-sky days’ in any given month. Mention sustainable design in Chinese circles and you immediately have everyone’s full attention.

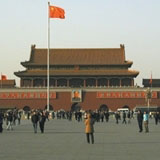

Arriving in Beijing after Shanghai is like landing in Moscow from Milan. The Soviet influence remains strong in a city of wide, austere avenues and Stalinist architecture. But, as in Shanghai, Beijing’s premier design colleges are thinking ahead. At the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where tutors have created the official colour palette for the Olympics, there are exciting developments in digital media. Here, says Li Zhenhua, a design curator who helped bring the Communicate graphics show from London’s Barbican to Beijing, there is a critical edge that reflects genuine potential for creative leadership. A new design research lab opens at CAFA in July, as part of a dedicated drive to beef up postgraduate design education in China.

It is a similar story at the élite Tsinghua University, which has absorbed Beijing’s Central Academy of Art and Design into the Chinese equivalent of Oxford or Cambridge. A spacious and, as yet, unfilled new building on Tsinghua’s elegant campus stands as a symbol of future design pre-eminence.

China is still a welcoming workplace for western design expertise, despite a loose and wild approach to intellectual property. After Shanghai and Beijing are a string of ambitious regional cities with populations of about four million, and this is where many believe the new goldrush in design and architecture will happen.

But cashing in won’t be easy and much will depend on local collaborations. Behind the rapid transformation to bling culture is a careful and deliberate build-up of a design system that will give China the creative tools to be a global player in its own right, and not just the receiving house for the best design the rest of the world can offer.

Jeremy Myerson is professor of design studies and director of InnovationRCA at the Royal College of Art in London

-

Post a comment